I’m sure you all saw coverage of the exhibit showing portraits painted by former president George W. Bush. The show at the George W. Bush Presidential Center at Southern Methodist University was front page news, pictorially, in New York — here in The New York Times and here in The Wall Street Journal — and probably elsewhere too.

I’m sure you all saw coverage of the exhibit showing portraits painted by former president George W. Bush. The show at the George W. Bush Presidential Center at Southern Methodist University was front page news, pictorially, in New York — here in The New York Times and here in The Wall Street Journal — and probably elsewhere too.

It was criticized as amateurish by some — most? — and I don’t disagree. So was Winston Churchill’s art, but it was still interesting that he could as well as he did, given all the other things Churchill did so well.

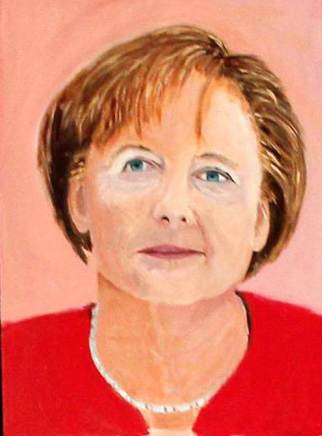

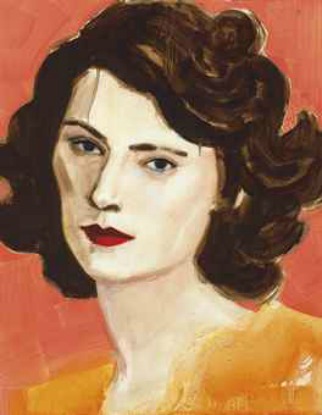

Bush’s art, meanwhile, bears a lot of similarity, to me, to that of the overrated Elizabeth Peyton, whose work has sold for more than $1 million. Her portrait of Elizabeth II at sixteen, below left (versus Bush’s view of Angela Merkel, at right), fetched $518,500 at Christie’s. Others I know see Alex Katz in there and one misguided soul sees “a touch of Beckmann.” It would be a very tiny touch, imho.

Bush’s art, meanwhile, bears a lot of similarity, to me, to that of the overrated Elizabeth Peyton, whose work has sold for more than $1 million. Her portrait of Elizabeth II at sixteen, below left (versus Bush’s view of Angela Merkel, at right), fetched $518,500 at Christie’s. Others I know see Alex Katz in there and one misguided soul sees “a touch of Beckmann.” It would be a very tiny touch, imho.

So why cheer? The answer it in the NYT article:

Now on some days [Bush] spends three or four hours at his easel. The man who never much cared for museums — he rushed through the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg, Russia, in 30 minutes flat — told a private gathering the other day that he now could linger in art exhibits for hours at a time studying brush strokes and color palettes.

Bush’s newfound feelings underscore research findings that getting people to participate in art themselves leads them to visit museums. If we teach children to make art, no matter how primitive, a good proportion are likely to grow up to appreciate art and be museum visitors. That’s a better strategy for museums, it seems to me, than attracting those elusive young people with dance parties and other activities that have little, or nothing, to so with the art on view.