U.S. Attorney Richard Callahan, who has been hounding the St. Louis Art Museum to return an Egyptian mask it purchased in 1998 for about a half million dollars, has told the St. Louis Post-Dispatch that “his office only had “a lack of record showing a lawful transfer,†not proof the mask was stolen.” The Justice Department has therefore abandoned its effort to force SLAM to return the mask, letting yesterday’s deadline for taking legal pass without an additional filing.Â

To recap, as the P-D wrote:

To recap, as the P-D wrote:

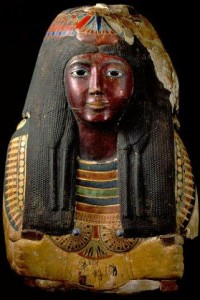

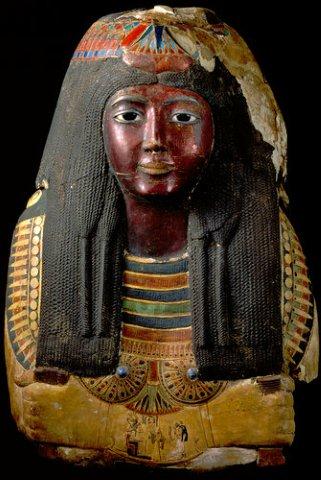

The mask was excavated in 1952 from a storage room near the step pyramid of Saqqara and was one of the items found with the mummified body of Ka-Nefer-Nefer, a noblewoman at the court of Ramses II.

The mask disappeared from storage in Egypt sometime between 1966 and 1973. The museum bought the mask in 1998 from a New York art dealer for $499,000.

When Egyptian authorities learned in 2006 that the museum had the mask, they began trying to get it back.

After negotiations failed, the federal government threatened to sue, but lawyers for the museum beat them to the courthouse, filing their own suit in January of 2011.

Then, in 2012, the government’s seizure case was dismissed on the grounds that government proved nothing. The U.S. Attorney’s office appealed, but in June the Court of Appeals agreed with the first ruling. And now:

“The evidence that we had showed that the mask was in the lawful possession of the Egyptian authorities for several years, and then there was a period with no activity,†[Callahan] said. After that, “the mask was not in the possession of the Egyptian authorities anymore and there was no paperwork to support the theory that it lawfully left.â€

The museum has said that the mask was part of a private collection in the 1960s, and was purchased in Switzerland by a Croatian collector, Zuzi Jelinek. Jelinek sold the mask to Phoenix Ancient Art in New York in 1995, the museum said.

The museum has said that it researched the mask’s ownership history before buying it, reaching out to Interpol, the Art Loss Register and others.

As The Art Law Report noted, however, “This does not necessarily end all wrangling over the mask. Egypt itself, which has steadfastly maintained that the mask was taken illicitly before being imported, could still take legal action in the U.S. whether that would face timeliness or statute of limitations/laches issues would likely be the question Egypt first considers.”

But SLAM has the mask (above), for now, which is on view in Gallery 130.