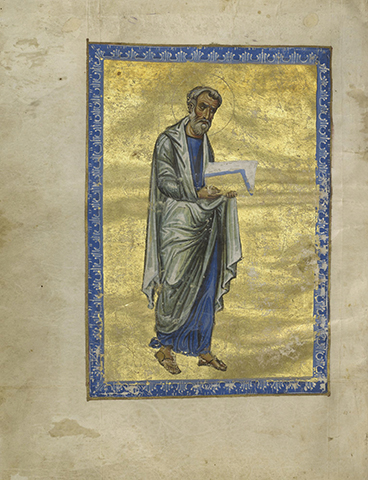

Here’s another mayor I like, one who understands the power art: Francisco de la Torre, of Malaga, Spain. He just signed an agreement with Russia, which will open a branch of the State Russian Museum in his city in the south of Spain. It’s a 10-year pact through which the Russian museum will lend about 100 works from its collection, plus about 60 works of art in special exhibitions, to a space in a former tobacco factory, dating to the 1920s, that also contains an automobile museum (pictured).  The Russian museum, located in St. Petersburg, promised to send a range of art, from 15th-century icons to 20th-century paintings, including Cubist, Constructivist and Socialist Realist ones.Â

This deal comes on on the heels of one de la Torre sealed last year with the Centre Pompidou. It will open a satellite in Malaga next year in a space on the city’s waterfront.

This deal comes on on the heels of one de la Torre sealed last year with the Centre Pompidou. It will open a satellite in Malaga next year in a space on the city’s waterfront.

I learned of the new Russian deal from reports published both in The Art Newspaper and also in EuroWeeklyNews. “Over the last few years, Malaga has spent millions on its cultural sector, which is a major tourism draw,” EuroWeekly News said.Â

Malaga is of course where Picasso was born, and tourists can visit his birthplace/museum, the Picasso Museum-Malaga, the Museo Carmen Thyssen, the Contemporary Arts Center and many other arts related venues. Trip Advisor puts it as the #6 destination in Spain, saying “Today, art is everywhere– you can experience exhibits dedicated to glass and crystal, classic cars, contemporary installations, and, of course, the works of Picasso…”

Though I am sometimes skeptical of museum satellites, this one seems good both for Russia and Malaga, not to mention art and art-lovers.