You know Leonard Lauder as an unsurpassed collector of Cubism, but what turned him into a collector was something completely different. He actually began collecting as a boy of five or six, or maybe seven. As he tells the story, his father gave him five cents as an allowance, and he spent the whole thing buying five postcards of the Empire State Building — all the exact same image. “Five,” he told me, “is a collection.”

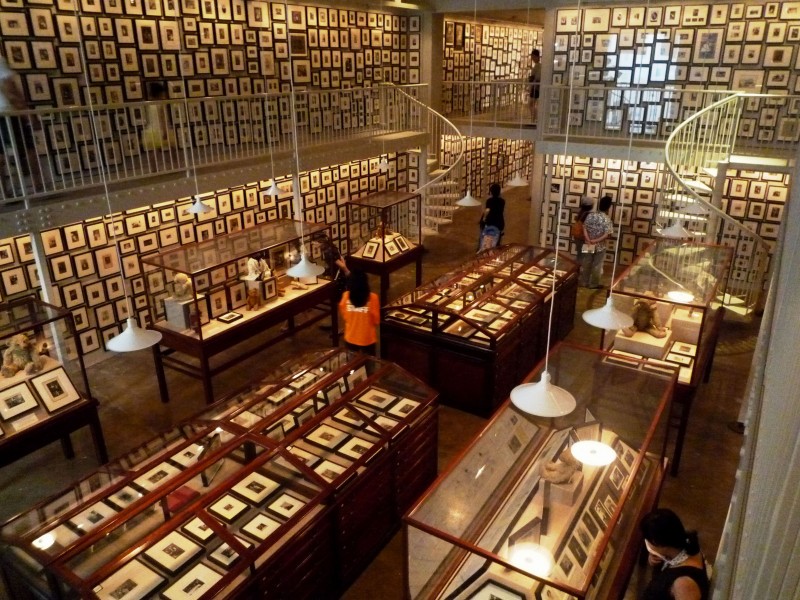

I tell this story, in slightly different form, in an article headlined The Pleasures of Postcards for The New Yorker.com, published as to coincide with the opening this past Wednesday of The Postcard Age: Selections from the Leonard A. Lauder Collection at  the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Billed as “the first general exploration of the postcard as an artistic medium at a major museum,” the show contains about 700 postcards (all a promised gift to the MFA).

I tell this story, in slightly different form, in an article headlined The Pleasures of Postcards for The New Yorker.com, published as to coincide with the opening this past Wednesday of The Postcard Age: Selections from the Leonard A. Lauder Collection at  the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Billed as “the first general exploration of the postcard as an artistic medium at a major museum,” the show contains about 700 postcards (all a promised gift to the MFA).

Last month, I visited Lauder in his office at Estee Lauder Cos., and paged through the catalogue with him — trying to get him to pick out favorites so that we could do a slide show for The New Yorker. Hah! I came home with at least 100 bright yellow post-it notes hanging out of the catalogue — that’s how he marked them. We actually ran through a pad of them, and had to ask for more.

Courtly and ever genial, Lauder protested “I love them all!†And when I urged him to be more selective, he countered, “Why should I do your job? I’m not even getting paid for this. Everything in here is my favorite.â€

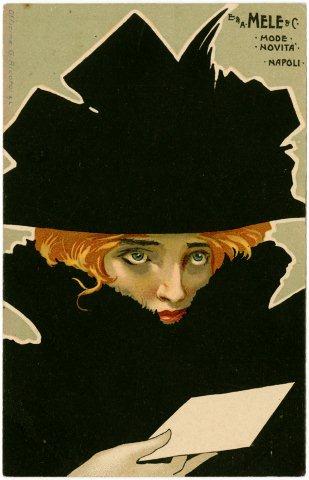

It seems the curators, Lynda Klich and Benjamin Weiss, had the same experience: the exhibit started out as 400 postcards, was quoted as 450 in the summer, and is now 700. Lauder certainly helped select and chose the cover card, a flirtatious blue-eyed redhead, swathed in black fur and fancy hat, that was the public face of Italys’s Mele department store chain circa 1920. “I got it from an Italian auction run by a dealer in Milano, about seven or eight years ago,†Lauder says. “I paid about $50.â€

Lauder’s interests in postcards sometimes shift from theme to theme, with the most recent being Wiener Werkstatte post cards. That, he says, “has been for a long time now, and there’s nothing behind it yet.”

Still, you can see he loves these postcards — if you go to the slide show on The New Yorker site, you’ll find his comments on 14 of the ones we ended up choosing as representative of his favorites. (You can see them all on one PDF that the MFA made for me after Lauder and I spoke  [Lauder_The_Postcard_Age-Selections], but not the captions — maybe it will whet your appetite.)

Now why would Lauder, worth billions, keep buying postcards when he can afford Picassos?

When I asked him that, a trace of incredulity passed over his face. “I like beauty, and you can never surround yourself with enough beauty,†he said. Plus, postcards connect him to history, another of his interests. Lauder admits to being an incurable collector, and says he gets as much pleasure from postcards as he does from his paintings. “The paintings I buy relate to one another, and the postcards do, too,†he says. No matter what he’s buying, “the thrill for me is the hunt.â€

When I asked him that, a trace of incredulity passed over his face. “I like beauty, and you can never surround yourself with enough beauty,†he said. Plus, postcards connect him to history, another of his interests. Lauder admits to being an incurable collector, and says he gets as much pleasure from postcards as he does from his paintings. “The paintings I buy relate to one another, and the postcards do, too,†he says. No matter what he’s buying, “the thrill for me is the hunt.â€

Then, he added, “Many people collect to possess. I collect to preserve, and no sooner do I have a collection put together than I am looking for a home for it in a public institution.â€Â As usual, he declined to say anything about where his magnificent collection of paintings will go.

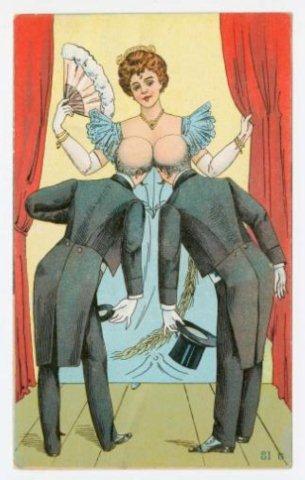

I’ve posted the beautiful cover card and a funny one, that made Lauder laugh, here.

Photo Credits: Courtesy of the MFA