It’s not just great art that draws so many people to TEFAF Maastricht; the fair is also popular because it’s fun — though not like the stay-up-all-night, get-plastered parties at Art Basel Miami Beach. (Maybe there’s some of that, but the only whiff I heard of it last week came from two art-history grad students, at the fair and in other European art sites on a class trip, who said they knew of other students who’d been drinking till 6 a.m. on the morning of Mar. 16.)

In Maastricht, much of the fun takes place at the fair in the MECC convention hall, starting at noon on Thursday with a “by-invitation” vernissage. Champagne and other drinks, plus coffee, flows all day long until 8 or 9 p.m., as does the food. Everywhere you turn, some is offering you something to eat or drink — though there are also sit-down cafes where the public can buy food and drink on later days. You’re always running into someone you know — museum directors and curators, collectors, dealers who don’t have booths, etc. It’s a gabfest, an artfest and a foodfest rolled into one. More than 10,000 people attend, and in one of those backward twists of fate, these people pay nothing to enter — they’re the big-spenders who are treated, while ordinary people, allowed in on Friday and until Mar. 25, pay €55 per person or €110 for a season ticket, both including the one catalogue.

In Maastricht, much of the fun takes place at the fair in the MECC convention hall, starting at noon on Thursday with a “by-invitation” vernissage. Champagne and other drinks, plus coffee, flows all day long until 8 or 9 p.m., as does the food. Everywhere you turn, some is offering you something to eat or drink — though there are also sit-down cafes where the public can buy food and drink on later days. You’re always running into someone you know — museum directors and curators, collectors, dealers who don’t have booths, etc. It’s a gabfest, an artfest and a foodfest rolled into one. More than 10,000 people attend, and in one of those backward twists of fate, these people pay nothing to enter — they’re the big-spenders who are treated, while ordinary people, allowed in on Friday and until Mar. 25, pay €55 per person or €110 for a season ticket, both including the one catalogue.

Fashion makes an appearance at the vernissage now and then — people were talking about outlandishly high heels on some women this year — but mostly, I thought, people were well-dressed without being overly showy. I heard of one woman who came dressed in a bright orange ball gown (the color of the Dutch royal family), her hair elaborately fashioned in an evening style — but I didn’t see her.

The hall is beautifully transformed by tulips, magnolias and cherry blossoms (about 100,000, all told, TEFAF says).

The hall is beautifully transformed by tulips, magnolias and cherry blossoms (about 100,000, all told, TEFAF says).

And then the art. You can see the exhibitors here. Suffice it to say that the dealers all try to bring their best, but this year, masterpieces were few and far between. Take your pick of pickers: here’s Souren Melikian in the International Herald Tribune; here’s Faye Hirsch in Art in America, and here’s what Art Info had to say.

As for sales, Art Market Monitor has links to many stories, so I’m going to send you there.

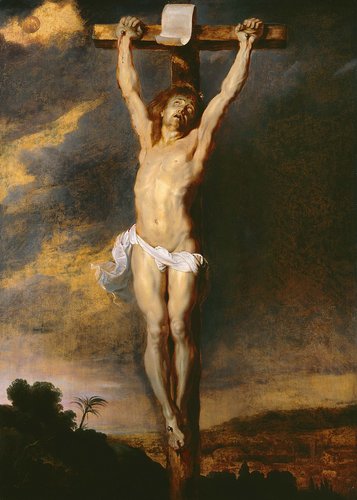

But Paul Jeromack has the coup: he has reported for Artnet that Ned Johnson, of Fidelity Investments, laid out some $12 million to buy Mankind’s Eternal Dilemma – The Choice Between Virtue and Vice by Frans Francken for the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. Here’s the link, and this is what it looks like: