Funny thing about collecting: Most of the time, collections simply grow, rarely shrinking, and they need more space. Case in point: Dallas collectors Cindy and Howard Rachofsky. They and another couple, Amy and Vernon Faulconer, are opening a building to show their collections called The Warehouse. It’s 18,000 sq. ft. and is a joint venture with another couple, Amy and Vernon Faulconer. The first show is titled Parallel Views: Italian and Japanese Art from the 1950s, 60s and 70s. The Warehouse will also sometimes borrow works from other private collections and museums, too.  (Hat tip to The Art Newspaper.)

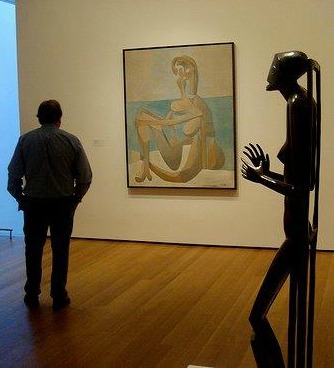

You’ll recall that the Rachofskys had shown some of their collection in their home, which was designed by Richard Meier (at left). Its website now says that that is closed to the public, and that the couple has:

You’ll recall that the Rachofskys had shown some of their collection in their home, which was designed by Richard Meier (at left). Its website now says that that is closed to the public, and that the couple has:

moved all of our educational programming to The Warehouse. This will include all middle school, high school, university, and museum group visits, as well as more in-depth programs. The Warehouse is a new art space developed by two collecting couples – the Faulconers and the Rachofskys. The building contains about 18,000 square feet of exhibition space, divided into 16 galleries, and will show works from both the Rachofsky and Faulconer collections. We are very excited about the experience with art in this new space.

The Warehouse is accessible by guided visit only, and it’s free.

It’s also open only to groups in pre-arranged visits, though individuals may go to Sunday Open Houses and Friday Public Visits.

The Rachofskys are part of the collectors’ group in Dallas that in 2005 agreed to donate hundreds of millions of dollars to the Dallas Museum of Art. Their bequest, at the time at least, involved “about 400 works by Mr. Richter, Donald Judd, Bruce Nauman, Sigmar Polke, Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Tom Friedman, Kiki Smith, Robert Gober, Mona Hatoum, Jim Hodges, Robert Irwin and others. It also includes the house that Mr. Rachofsky, a hedge fund manager, began building in the 1980’s as a residence and came to use as a gallery when it was completed in 1996,” according to The New York Times.

That house was about 10,000 sq. ft. So they are nearly doubling their space with The Warehouse.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the Rachofskys