On Saturday, The Wall Street Journal published my latest entry in its Saturday Masterpiece column, about Enguerrand Quarton’s Pietà of Villeneuve-lès-Avignon, and all I can say is that we picked the right artwork this time, for sure, based on the feedback I’ve received so far. Many people–not art historians, of course, but art lovers nonetheless–have told me that they’ve never noticed the work in the Louvre. Yet is it a large work, more than 5 by 7 feet.

On Saturday, The Wall Street Journal published my latest entry in its Saturday Masterpiece column, about Enguerrand Quarton’s Pietà of Villeneuve-lès-Avignon, and all I can say is that we picked the right artwork this time, for sure, based on the feedback I’ve received so far. Many people–not art historians, of course, but art lovers nonetheless–have told me that they’ve never noticed the work in the Louvre. Yet is it a large work, more than 5 by 7 feet.

That’s a detail of Mary Magdalene at left, one of Mary at right, and the whole work below, all courtesy of the Louvre.

As I told one friend, I blame its placement, up to a point. It’s in the French paintings galleries on the second floor and it’s one of the first paintings you see. But it is in a little room that seems like an entryway to larger galleries. While I was there in February, almost everyone gave it a quick glance and proceeded to the next room, which contained many more pictures.

Also, as I explain in my piece, ‘This [pieta]…would surely be as celebrated [as others] had it not been hidden in a dark, provincial chapel, its creator unknown and then disputed, for so long.” Quarton’s restraint in painting a work of such poignancy and pain makes it rise above other depictions of this scene.

Also, as I explain in my piece, ‘This [pieta]…would surely be as celebrated [as others] had it not been hidden in a dark, provincial chapel, its creator unknown and then disputed, for so long.” Quarton’s restraint in painting a work of such poignancy and pain makes it rise above other depictions of this scene.

A fascinating aspect of the story is that it was

discovered in 1834 by a young inspector of historical monuments named Prosper Mérimée—later the author of “Carmen,” the novella that inspired Bizet’s opera. Mérimée found it in a church in Villeneuve-lès-Avignon, a little town on the Rhone opposite Avignon.

Charles Sterling, a curator at the Louvre and later at the Metropolitan Museum, is also a hero of this story–he made the attribution to Quarton.

Aside from this work, only two other paintings are known to exist now by Quarton, the Virgin of Mercy in the Musée Condé in Chantilly, and the Coronation of the Virgin in a hospice in Villeneuve-lès-Avignon–but we know that he made others, because the documents detailing six commissioned works can be found in French archives.

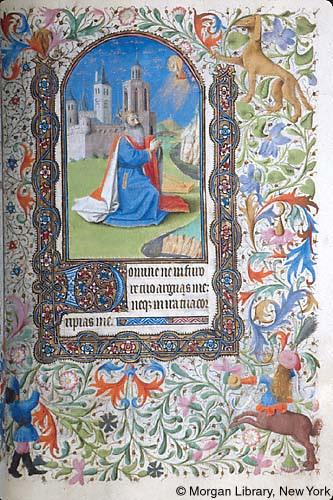

Obviously, American museums own no paintings by Quarton, but he was also an illuminator, and the Morgan Library owns one page, on which he did the miniature, and two others that are attributed to him. Here is the first: