It shows my naivété, after 20 years of teaching, that I still hold any illusions about academia. Until recently I had nurtured a belief that electronic music was one area of music in which the otherwise pervasive distinctions between academic and non-academic did not apply. After all, electronic music is the only department in which (you will excuse the term) Downtown composers have been able to find positions in universities. As far as I know, there are currently only two Downtown composers in the country who have ridden into permanent teaching positions on skills other than electronic technology; one of those, William Duckworth, did so on his music education degrees, and the other, myself, masqueraded as a musicologist. All the others work in electronic music, where, I fondly presumed, open-mindedness prevailed.

It’s not true. I’ve been becoming aware that, even among the Downtowners, there is a standard academic position regarding electronic music, and am learning how to articulate it. I’ve long known that, though much of my music emanates from computers and loudspeakers, I am not considered an electronic composer by the “real electronic composers.†Why not? I use MIDI and commercial synthesizers and samplers, which are disallowed, and relegate my music to an ontological no-man’s genre. But more and more students have been telling me lately that their music is disallowed by their professors, and some fantastic composers outside academia have been explaining why academia will have nothing to do with them.

The official position seems to be that the composer must generate, or at least record, all his or her own sounds, and those sounds must be manipulated using only the most basic software or processes. Max/MSP is a “good†software because it provides nothing built in – the composer must build every instrument, every effects unit up from scratch. Build-your-own analogue circuitry is acceptable for the same reason. Sequencers are suspect, synthesizers with preset sounds even more so, and MIDI is for wusses. Commercial softwares – for instance, Logic, Reason, Ableton Live – are beyond the pale; they offer too many possibilities without the student understanding how they are achieved. Anything that smacks of electronica is to be avoided, and merely having a steady beat can raise eyebrows. Using software or pedals as an adjunct to your singing or instrument-playing is, if not officially discouraged, not taught, either. I’m an electronic amateur, and so I won’t swear I’m getting the description exactly right. Maybe you can help me. But at the heart of the academic conception of electronics seems to be a devout belief that the electronic composer proves his macho by MANIPULATION, by what he DOES to the sound. If you use some commercial program that does something to the sound at the touch of a button, and you didn’t DO IT YOURSELF, then, well, you’re not really “serious,†are you? In fact, you’re USELESS because you haven’t grasped the historical necessity of the 12-tone language. Uh, I’m sorry, I meant, uh, Max/MSP.

Where does this leave a composer like Henry Gwiazda, whom I have often called the Conlon Nancarrow of my generation? He makes electronic music from samples taken verbatim from sound effects libraries, and you know what he does to them? Nothing. Not a reverb, not a pitch shift, not a crossfade. He just places them next to each other in wild, poetic juxtapositions, and it’s so lovely. From what music department could he graduate doing that today? Is he rather, instead of Nancarrow, the Erik Satie of electronic music? the guy so egoless (or simply self-confident) that he doesn’t have to prove to you what a technonerd stud he is with all the manipulations he knows how to apply?

Now, there is one aesthetic fact so obviously incontrovertible that it hardly merits mentioning: a piece of music is not good because a certain type of software was employed in making it, nor is it bad because a different type of software was applied. Compelling music can be achieved with virtually any kind of software, and so can bad. You’d have to be a drooling moron to believe otherwise. Given that patent truth, it would seem to follow that there is no type of software a young composer should be prevented from using. The question then follows, are there pedagogical reasons to avoid some types of software and concentrate on others? I am assured that there are: 1. Since softwares come and go, it’s important that students learn the most basic principles, so that they can build their own programs if necessary, rather than rely on commercial electronics companies. And, 2. Commercial software doesn’t need to be taught, all the student needs to do is read the instruction manual and use it on his own.

Let’s take the second rationale first. As someone who just struggled six months with Kontakt software just to get to first base, I don’t buy it. There are a million things Kontakt will do that, at my current rate, it will take me until 2060 to figure out. Even after wading through the damn manual, I’d give anything for a lesson in it. But even given that some softwares, like Garage Band, are admittedly idiot-proof, there are a million programs out there, and a young composer would benefit (hell, I’d benefit) from an overview of what various packages can do. How about a course in teaching instrumentalists or vocalists how to interact with software? A thousand working musicians do it as their vocation, but academia seems uninterested in helping anyone reach that state. It’s unwise to base one’s life’s work on a single, ephemeral software brand, Max as well as anything else – but knowing how to use a few makes it easier to get into others, and some of my more interesting students have subverted cheap commercial software, making it do things for which it was never intended.

Rationale number one is more deeply theoretical. I’m all for teaching musicians first principles. You don’t want to send someone out in the world with a bunch of gadgets whose workings they don’t understand, dependent for their art on commercial manufacturers. Good, teach ‘em the basics, absolutely. You teach ‘em circuit design, I’ll teach ‘em secondary dominants. But why should either of us mandate that they use those things in their creative expression? Creativity, like sexual desire, has a yen for the irrational, and not every artist has the right kind of imagination to get creative in the labyrinth of logical baby steps that Max/MSP affords. I’ve seen young musicians terribly frustrated by the gap between the dinky little tricks they can do with a year’s worth of Max training and the music they envision. I heard so much about Max/MSP I bought it myself, and now have a feel for how depressingly long it would take me to learn to get fluent in it. I thought it must be some incredibly powerful program, from what I kept hearing about it – it turns out, the technonerds love it because it’s incredibly impotent in most people’s hands, until you’ve learned to stack dozens of pages of complicated designs.

There are at least two types of creativity that apply to electronic music, probably more, but at least two. One is the creativity of imagining the music you want to hear and employing the electronics to realize it. Another is learning to use the software or circuitry and seeing what interesting things you can finagle it into doing. There are certainly some composers who have excelled at the second – David Tudor leaps to mind. Perhaps there are a handful who have mastered the first in terms of Max/MSP, but it’s a long shot. Of course, if you’ve got the type of creative imagination that flows seamlessly into Max/MSP, by all means use it. “Good music can be achieved with any kind of software.†But why does academia turn everything into an either-or situation, whereby if A is smiled upon, B must be banished?

There’s an analogue in tuning. I’m a good, old-fashioned just intonationist with a lightning talent for fractions and logarithms. I can bury myself in numbers and get really creative. In nine years of teaching alternate tunings, I can count on one hand the students who have shown a similar talent. Faced with pages of fractions, most would-be microtonalists freeze up and can’t get their juices flowing. Were I a real academic, I would respond, “Tough shit, maggot – this is the REAL way to do microtonality, and if you can’t handle it, then you’re on your own.†But I’m not like that, and I let students work in any microtonal way they can feel comfortable, whether it’s the random tuning of found objects or just pitch bends on a guitar – as long as they understand the theory underlying it. Likewise, some young composers get caught up making drums beat and lights blink in different patterns in Max/MSP, lose sight of their goal, and never make the electronic music they’d had in mind.

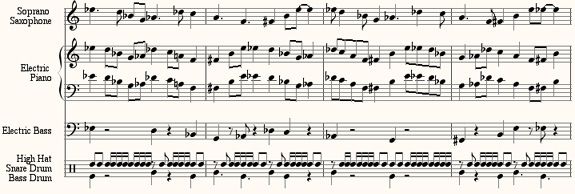

In fact, many years of listening to music made with Max/MSP, by both professionals and students, have not impressed me with the software’s results. I’ve heard a ton of undecipherable algorithms, heard a lot of scratchy noise, and I’ve heard instrumentalists play while the MSP part diffracts their sounds into a myriad bits whose relevance I have to take on trust. In the hands of students, the pieces tend to come out rather dismally the same – and not only students. The only really beautiful Max/MSP piece I can name for you is John Luther Adams’s The Place Where You Go to Listen, and you wanna know how he did it? He worked out just the effects he wanted on some other software, and then hired a young Max-programming genius, Jim Altieri, to replicate it. He envisioned the sound, the effect, the affect, but he knew he didn’t possess the genius to create the instrument he needed. Meanwhile I hear lots of beautiful music by Ben Neill, Emily Bezar, Mikel Rouse and others using commercial software that does a lot of the work for them. If we can talk about software as an instrument (and we should), there’s a talent for making the instrument, and there’s a talent for playing the instrument. To assume that one shouldn’t be allowed to exist without the other is to claim Itzhak Perlman isn’t really a violinist because he didn’t carve his own violin. It’s ludicrous.

In short, it appears that academia has applied the same instinct to electronic music as to everything else: find the most difficult and unrewarding technique, declare it the only valid one, take failure as evidence of integrity, and parade your boring integrity at conferences. Whatever happened to the concept of artist as a magician with a suspicious bag of tricks? Art is about appearances, not reality, so who cares if you cheat? Our society is truly upside down. Our politicians and CEOs, whom one could wish to keep honest, dazzle us with virtuoso sleight-of-hand, while our musicians, who are supposed to entertain us, meticulously account for every waveform. It’s completely bass-ackwards.

Do I overgeneralize? I hope so. Please tell me that there’s an electronic music program that doesn’t make this pernicious distinction, and I will send droves of students applying to that school. I was living in a fool’s paradise, and I’m only reacting to what I’m hearing – from disenfranchised young composers, from electronic faculty who proudly affirm the truth of what I’m saying as though it’s a good thing, from fine composers who are wizzes at commercial software. One brilliant electronic student composer this year insisted that I advise his senior project: me, who can barely configure my own MIDI setup. I had nothing to teach him; our “lessons†consisted of me grilling him with questions about how to get the electronic effects I was trying to achieve. But I gave him permission to use synthesizers, and found sounds, and let him play the piano in synch with a prerecorded CD. I didn’t emasculate his imagination by forcing him back into a thicket of first principles from which he would never emerge. His music was lovely, crazy, expressive. Another student, a couple of years ago, enlisted me for a children’s musical he made entirely on Fruity Loops. It was a riot.

And so I say to all composers who got excited in high school about the possibility of musical software but feel intimidated by their professors’ insistence on doing everything from scratch: go ahead, use Logic, and Reason, and Ableton Live, and Sibelius, and Fruity Loops, and synthesizers, and stand-alone sequencers, and hell yes, even Garage Band, with my blessing. Be the Erik Saties and Frank Zappas and Charles Iveses of electronic music, not the Mario Davidovskys and Leon Kirchners. Resist the power structure that would tie anvils to your composing legs, with a pretense that they’re only temporary. The dogmatic, defensive ideology that‘s in danger of being callsed Max/MSPism is merely an importation of 12-tone-style thinking into the realm of technology. Who needs it?

[N.B.: In the comments, some confusion is caused by the fact that there are two Paul Muller’s, with different e-mail addresses. At least they agree with each other.]

The most frequent and bitter complaint I’ve gotten about my book on Nancarrow over the years has been about the price. But I’ve just learned – over the

The most frequent and bitter complaint I’ve gotten about my book on Nancarrow over the years has been about the price. But I’ve just learned – over the

their star pianist Sarah Cahill (pictured) will play a piece of mine, “Saintly” from my Private Dances, along with works by others from the still-kicking set like John Adams, Terry Riley, and Mamoru Fujieda. There will also be some works for Disklavier presented, including a new work by Daniel David Feinsmith, my own Nude Rolling Down an Escalator, and a couple of Nancarrow’s Player Piano Studies. Sounds like one of those great San Francisco new-music marathons, with Cahill featured throughout (both my pieces are on the 5:30 concert). Wish I could say I’ll see you there, but I’ll be in upstate New York, kicking myself for not having moved to California right out of college like I was tempted to.

their star pianist Sarah Cahill (pictured) will play a piece of mine, “Saintly” from my Private Dances, along with works by others from the still-kicking set like John Adams, Terry Riley, and Mamoru Fujieda. There will also be some works for Disklavier presented, including a new work by Daniel David Feinsmith, my own Nude Rolling Down an Escalator, and a couple of Nancarrow’s Player Piano Studies. Sounds like one of those great San Francisco new-music marathons, with Cahill featured throughout (both my pieces are on the 5:30 concert). Wish I could say I’ll see you there, but I’ll be in upstate New York, kicking myself for not having moved to California right out of college like I was tempted to.