I thought I’d put up a more detailed example of an early totalist piece, to show precisely how composers started breaking away from minimalism in the early 1980s. Mikel Rouse’s Quick Thrust of 1984 is a work that both reaches back into minimalism’s most formalist concerns and also forecasts ideas that would later become widespread. For one thing, it was one of the first fully notated pieces for a pop instrumentation, written as it was, like most of his music of the ‘80s, for his rock-instrumentation quartet Broken Consort, consisting of soprano sax, electric keyboard, electric bass, and drum set. Secondly – it’s a 12-tone work. The composers whose work would later be called totalist loved minimalism’s formalism, hard-edged textures, reduced range of materials, impersonality, and amplified ensemble concept, but were not much enamored of its pretty, diatonic tonality (at least as manifested in the work of Reich and Glass). Few turned to 12-tone technique, nor did Mikel ever repeat the experiment as far as I know, but Quick Thrust is a bona fide piece of 12-tone totalist rock – perhaps the only one.

Thirdly, Quick Thrust is an example of music drawn from Schillinger technique, for Mikel studied with a Schillinger specialist when he came to New York in the early 1980s. Today Joseph Schillinger’s technique is more widely known by reputation than example, but in the 1930s and ‘40s, it was particularly picked up by Tin Pan Alley composers as an aid to churning out music in a hurry. Gershwin studied it; so did, later, Earle Brown. (Schillinger’s hefty two-volume exegesis of his methods is forbidding, but quite clear if you persevere. It tends to introduce a new principle and work its way up to a musical example, and is actually easier to follow if you kind of start with each musical example and work your way backward to the principle.) The technique is based in a faith in the ability of number systems and arithmetical techniques to generate musical forms of innate aesthetic attractiveness, and some of its devices had been presaged in Henry Cowell’s precocious book New Musical Resources.

One technique in particular resonated with Cowell: generating rhythms via what Schillinger called the interference of periodicities. This meant repeating several rhythms of different lengths, and using the sum of their resultant attacks as a melodic rhythm. For instance, the pattern made by the simultaneous repetitions of a dotted 8th-note at the same time as a repeated quarter gives the resultant 3-against-4, the rhythm known by the mnemonic device “PASS the GOD-damned BUTter.†Since only one rhythmic value is used for each rhythm, this is an interference of monomial periodicities. In Schillinger technique, one could also have a rhythm of two notes (say, quarter + 8th) against another two note rhythm, creating a binomial periodicity. The song “Fascinatin’ Rhythm,†in fact, starts with an interference of a sexonomial periodicity (8th, 8th, 8th, 8th, 8th, quarter, totaling 7 8th-notes in duration) against a 4/4 meter. (That Gershwin wrote the song long before studying Schillinger suggests why he was drawn to the technique.)

Quick Thrust is entirely a product of interferences of monomial periodicities. Mikel rather fanatically derived all of his rhythms based on periodicities of the Fibonacci numbers 2, 3, 5, and 8. Every rhythm was either the result of the sum attacks of repeated notes of these durations, or else of a larger rhythmic unit divided into 2, 3, 5, and 8 parts. For instance, the bass line was frequently the result of dividing a duration of 30 8th-notes into 2, 3, and 5 equal parts:

Note that the 12-tone row is run through the eight-note rhythm in a phasing relationship, the pitch row and rhythm row returning to their original relationship every 24 notes. This is, of course, a recurrence of medieval isorhythmic technique, in which a pitch row (called a color) and a rhythm (called a talea) go out of phase with each other. The practice was the structural basis of the 14th-century motet, died out around 1450, and was resurrected again by Messiaen in the first movement of his Quartet for the End of Time (1941) and Study No. 7 by Conlon Nancarrow (early 1950s). It has appeared in several totalist works, my own Desert Sonata (1994) included.

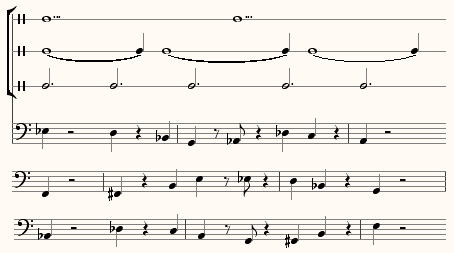

The upper lines of Quick Thrust, also treated isorhythmically, tend to be drawn from patterns of recurring small durations, such as this line made up from the summed attacks of notes 3, 5, and 8 8th-notes long:

At the beginning of the piece the entire 12-tone row is heard as an introduction, upon which the bass line enters, and then the keyboard and saxophone, creating a texture of three Schillinger rhythms at once, the same tone-row cycling through all three:

Notice that the high hat rhythm follows that of the keyboard, basically doubling it, and that the drums follow the bass line. Mikel never used any other transposition or form of the row (no retrogrades or inversions), for an effect that has always reminded me of the second movement of Stravinsky’s Threni, where he does something very similar. Others will be reminded of the young Steve Reich in the ‘60s, using the same row form over and over until his teacher Luciano Berio finally asked, “Steve, if you want to write tonal music, why not just write tonal music?â€

And now, ladies and gentleman, you can hear Quick Thrust in its five-minute entirety here. (By the way, there has never been a score to Quick Thrust – Mikel gave me the individual instrumental parts for his music from those years, and I’ve had to assemble the scores myself.)

I emphasize that this piece represents one of the initial starting points of what has been called the totalist, or metametric, movement. Like so much postminimalist music of the early ‘80s, it is minimalist compositionally, but not perceptually. Its repetitiveness is intricately disguised. Its strict processes are not linear but global, real to the composer but not heard by the listener. (Many movements of Bill Duckworth’s earlier Time Curve Preludes are similar in this respect.) Quick Thrust is a fantastically clear example of a certain kind of rhythmic and structuralist thinking that was pervasive, “in the air,†in the mid-1980s among a certain kind of minimalism-impressed-but-not-quite-impressed-enough composer – not characteristic of the totalist movement as a whole, but quite typical of several months in 1983/84.

This kind of intense structural fanaticism was soon left behind. Number patterns remained in use in the works of many composers, such as Michael Gordon, Art Jarvinen, Rhys Chatham, Glenn Branca, Ben Neill, Evan Ziporyn, Diana Meckley – but usually in textures of more intuitive freedom. The interference of periodicities became the basis of the fifth movement of Chatham’s An Angel Moves Too Fast to See, at least part of Branca’s Sixth Symphony “Devil Choirs at the Gates of Heaven,†and several pieces of my own in the ‘80s, most concentratedly my 1987 piano piece Windows on Infinity – though my interest was always in longer time stretches and larger prime numbers, with events occurring every 53 8th-notes, every 71, every 103, and so on. When Mikel heard a concert of my music by Essential Music in 1989, and I heard his Quick Thrust and other Broken Consort works soon afterward in 1990, we got together, started talking, and realized that we had been on the same track. You could look it up.

Subsequently I wrote about Quick Thrust and other works with similar rhythmic tendencies in an article in a 1994 issue of the academic journal Contemporary Music Review. Possessing entire file cabinets full of unpublished scores by composers of my generation, I could write another article like this every month. But very few people have seen that article, and articles in academic journals pretty much disappear into libraries, to be scoured at rare intervals by the occasional researcher. I’ve got tenure, I don’t need any more resumé lines, thanks. Now that I can put both score examples and recordings on the internet, I would far rather publish here, where I am am actually read. And since few people who weren’t immediately involved in the scene were aware of techniques used by the music I’ve spent my life writing about, I hope that with this method of presentation I can bring the underground history of the 1980s and ‘90s out into the open and help the world catch up. Does it sound like I’ve finally begun that book on Music After Minimalism that I’ve been threatening for years? I guess I have.