My post on the postclassical paradigm for meter, though it dealt with Janacek, was particularly relevant to progressive music of the last 20 years. The tendency to think about meter as quantity, without heirarchical subdivisions of the measure, was avidly developed by the composers who were part of the totalist movement of the 1980s and ‘90s: Mikel Rouse, Michael Gordon, John Luther Adams, Art Jarvinen, Ben Neill, Evan Ziporyn, Tim Brady, Diana Meckley, David First, Larry Polansky, myself, arguably Glenn Branca and Rhys Chatham, and a few others. In the wake of minimalism we created a new conception of ensemble rhythm that left the traditional concept of meter behind. (I speak of totalism in past tense now, because I have no clear evidence that the movement is continuing as such, most of its original proponents – myself included – having more or less moved on to other issues, relegating rhythmic complexity to the background.) Minimalism is still, to this day, ignorantly caricatured as a simplistic music. But by 1983, the young composers most impressed with it were hearing it as a technical basis for a new rhythmic practice so sophisticated that there are still only a handful of music ensembles who have learned to negotiate it.

In particular, totalism was, almost centrally, concerned with using conventional musical notation as a language with which to generate a feelable and performable rhythmic complexity. Some of the simple polyrhythms (usually 3-against-2 or 4-against-3) embedded in Steve Reich’s and Charlemagne Palestine’s music, as well as the irregular phrase rhythms found in Phil Glass’s early work, suggested that minimalism’s stasis might support even greater rhythmic complexity. Of course, the previous few decades had been awash in rhythmic complexity, but mostly of a conceptually abstract kind: the polyrhythms of Elliott Carter, Stockhausen, et al usually avoided articulating a steady beat for any period long enough to register tempo contrasts. Inspired by minimalism, rock, and world music, the totalists wanted a music of steady beats that allowed the listener to focus on tempo contrasts in a sustained way. Nancarrow’s player piano music offered a model, but his music generally wasn’t performable, nor was his emphasis often on sustained steady beats. What the totalists wanted was a new kind of ensemble performance that retained minimalism’s clear, doubled lines and motoric rhythm, but also offered a perception-stretching simultaneity of rhythmic layers, usually within the confines of comfortable live performance.

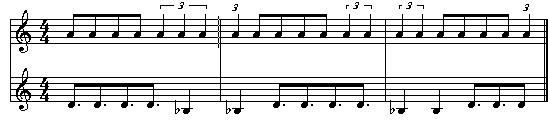

The trick was to use the inherent polyrhythmic implications of different note durations. The most common totalist strategy was to mix different pulses of quarter-notes, dotted quarter-notes, and triplet quarter-notes. Michael Gordon had gone down this road as early as 1983 with his Thou Shalt!/Thou Shalt Not!. By 1993, in pieces like Yo Shakespeare, he had stripped down to almost pure rhythm (the doubled instruments here being guitars and electric keyboards):

(Hear the excerpt here. I have chosen the excerpts here for their rhythmic clarity, not because they are the most well-developed or beautiful examples of the style. If I were trying to convince the reader that totalist music is a compelling repertoire, I might in some cases have chosen other and more recent examples. My purpose at present is merely to prove that in the ‘80s and ‘90s, these composers were generating their music from strikingly similar rhythmic ideas.) Note the use of triplet quarter-notes in groupings of other than three. This was not unprecedented; Henry Cowell suggested it in New Musical Resources, Boulez toyed with the idea in Le Marteau sans Maitre, and I used it myself starting with my I’itoi Variations of 1985. What it means performance-wise is that the performer has to forget about the meter entirely (though it still conforms to 4/4 in this example) and, having internalized the tempo of the triplets, play them in tempo irrespective of bar lines. The meter’s 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 must be forgotten about.

The most fertile totalist contrast was that between triplet quarter-notes and dotted 8th-notes, either of which could easily be sustained against a dominant quarter note beat. The typical totalist ensemble circa 1993 would keep a quarter note beat in common by tapping their feet or nodding their heads, and achieve a faster 8-against-9 rhythm by having half the ensemble play triplet quarters and the other half dotted eighths. It was amazingly effective – even if the effect of everyone nodding their head to a beat no one ever played was, visually, a little humorous.

My own technique has often been not to play these tempos simultaneously, but to shift back and forth between them, as in my Snake Dance No. 2 of 1994:

![]()

(Hear the excerpt here.) By this point, of course, the “meter†has become an irrelevant bookkeeping activity: the fact that 13/8 follows 23/16 is of no importance whatever, for either the performers or the listener. One performs this music by getting a feel, throughout the piece, for how fast to go when the beats are quintuplet 8ths, how fast when they are dotted 8ths, and so on. It takes awhile to rethink your rhythmic sense this way. The day the group Essential Music started rehearsing Snake Dance No. 2, I came home to two answering-machine messages from percussionist Chuck Wood. The first was: “We just started rehearsing your piece. We hate you.†The second, from an hour later: “Actually, we’re getting the hang of it. It’s going to be all right.â€

Some totalist rhythmic strategies bear a closer conceptual relationship to minimalism. For instance, one can see the influence of Reich’s Piano Phase and other phase-shifting pieces in Murphy-Nights by Art Jarvinen, in which the keyboard plays an ostinato in 8/4 (32 16th-notes long) while the bass simultaneously plays an ostinato in 33/16, thus going out of phase one 16th-note with each repetition:

(Hear the excerpt here.) The other instruments come in over this in 6/4 meter. To this day I have no idea how the California E.A.R. Unit achieved this in performance, since it doesn’t seem possible to conduct it.

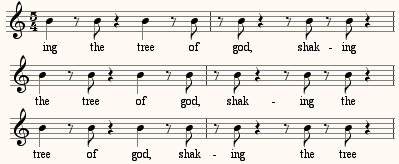

Mikel Rouse has engineered some of the most complex effects of totalism, inspired by his readings in A.M. Jones’s Studies in African Music and also his early immersion in Schillinger technique. Early pieces like Quick Thrust (1984) were based entirely on rhythms generated from patterns like 3-against-5-against-8. Much of his 1995 opera Failing Kansas was energized by five-beat phrases falling across the 4/4 meter, or the superimposition of 4/4 in the accompaniment with 12/8 in the lyrics (the 8th-note being equal). Mikel has also used intricate isorhythmic effects in which lyrics (and/or pitches) go out of phase with repeated rhythms, such as this devilishly difficult passage from “Never Forget a Face†on his 1994 album Living Inside Design:

(Hear the excerpt here.)

Too, John Luther Adams has achieved more notationally conventional but still difficult polyrhythmic textures by dividing a standard measure into 4, 5, 6, and 7 equal beats, much as Cowell suggested and as Nancarrow continued doing his entire life. Simply from rhythms alone, Adams’s In a Treeless Place, Only Snow (1999) is not too visually different from Nancarrow’s Piece for Small Orchestra No. 2:

Unlike all the other totalists, though, John’s music is soft and gentle, creating cloudy textures rather than perceptible tempo clashes.

Much more loudly, Rhys Chatham and Glenn Branca used totalist rhythmic structures in their works for massed electric guitars. Glenn has used simultaneous tempos of 3:4:5 in his Symphony No. 6 (1987-88) and a quasi-tempo canon of 7:8:12 in the second movement of his Symphony No. 10 (1994). In An Angel Moves Too Fast to See for 100 electric guitars (1989), Rhys solved the problem of many guitarists not being able to read music by employing a totalist strategy. He gave various sections of the guitar orchestra single chords to play at varying rhythmic intervals: every 5 beats, another evert 7, 8, 9, 11, and 16, the music resulting naturally from the rhythmic process. (Hear the excerpt here.)

Not all totalist music is live-ensemble-oriented. Ben Neill and Larry Polansky have both made computer-generated tempo continua with rhythms similar to those of the enesmble composers. For instance, Neill in his 678 Streams performs on trumpet over a computer-generated ambient texture in which tempos of 6-against-7-against-8 are apparent. Among many other types of experiment, Polansky has made rhythmic canons of prerecorded samples, using similarly Nancarrovian tempo relationships. My own Disklavier pieces, notably Unquiet Night, have gone much further out than my ensemble pieces, articulating steady beats of 7:9:11:13:15:17. Even so, the principle remains the same: the fact that we use inherent notation-based properties of MIDI sequencing means that we’re still using notation to generate ratio-based tempo relationships.

In terms of live performance, however, there’s a limit to how far one can take these rhythmic relationships, which strikes me as one reason totalism has probably ceased to cohere as a movement. Rouse, having reached the perceptible extreme of his type of complexity, has become more interested in overlayings and spatial separation in his home-produced recordings. Gordon has been writing for orchestras, which can’t be trained to execute these rhythms in any reasonable manner. As I write more and more for existing ensembles, I’ve had to sublimate my rhythmic schemes to the more subtle background level of structure. Perhaps only Adams continues to write in the same rhythmic style, and he was always more interested in a certain kind of cloudy sound and texture than in discrete rhythmic perception anyway. Many of these rhythms can’t be conducted; Essential Music can feel my 23/16 followed by 13/8, but how would you indicate it with hand motions? I’m not convinced there’s not a way, but the gung-ho incursion of strictly totalist music into the repertoire of conventional classical ensembles was never a very feasible option. Even so, classical musicians need to start learning to deal with some of these rhythmic techniques that have become quite common.

Of course, none of this is officially recognized in musical discourse. Some of the most authoritative critics in the business have stated publicly that the totalist movement never existed, so by mentioning it you’re likely to subject yourself to the most withering looks of condescension. If you happen to accidentally mention it, try to cover by saying, “Ohh… it’s just something I read in Kyle Gann,†with a dismissive wave of your hand, and you might get away with it. Remember: there’s no such thing as totalist music (wink, wink).