A few weeks back, in a guest-post on Engaging Matters, Roberto Bedoya extended an invitation for others to join him in blogging about “how the White Racial Frame intersects with cultural policies and cultural practices.†The proposition grew out of a series of posts (largely written by a bunch of white people, like me) focused specifically on the Irvine Foundation’s new participatory arts focus and, more generally, on (funding) diversity in the arts. I don’t feel qualified to address this topic and I’m positive I do not do it justice, but this is my sincere attempt to unpack some small part of this large issue. (You can read my previous posts on the the Irvine strategy here and here.)

Prologue on the white racial frame

A  few days ago, DC theater director Eissa Goetschius posted on her Facebook page:

Because I was curious, I just looked through the archives of the Shakespeare Theatre online to try to see how many directors of color have worked there over the years. Unless I missed some – which might be possible as this was only as scientific as googling the names I didn’t know – there have been two in all of their years of existence. Harold Scott directing OTHELLO and Rene Buch directing FUENTE OVEJUNA both as part of the ’90-’91 season. I REALLY HOPE I’M WRONG ABOUT THIS. SOMEONE TELL ME I’M WRONG. ‘Cause this means they haven’t had a person of color direct a show in over twenty years.

In a similar vein, about a week ago someone mentioned to me that it seemed like all the AJ bloggers were white. I don’t know all the AJ bloggers, so can’t confirm whether they are all white; and Elissa also gives the caveat that her search was possibly flawed. But if these figures are true, or even nearly true, they should strike us as remarkable. The question is, do they? On a day-to-day basis? Or do we take for granted that there is nothing all that strange about an absence of non-white directors and bloggers?

I am embarrassed that, for instance, I never noticed all the other AJ bloggers may be white.

When Roberto Bedoya issued his invitation/challenge, I felt I needed to read a bit about the “White Racial Frame” (a term credited to Joe Feagin). Here’s a paragraph I found to be useful (from Wikipedia):

The dominant white racial frame generally has several levels of abstraction. At the most general level, the racial frame views whites as mostly superior in culture and achievement and views people of color as generally of less social, economic, and political consequence than whites—as inferior to whites in the making and keeping of the nation. At the next level of framing, whites view an array of social institutions as normally white-controlled and as unremarkable in the fact that whites therein are unjustly enriched and disproportionately privileged. (Italics added.)***

There has been an ongoing discussion for decades now about the need and desire to diversify the arts sector; and notable progress has been made at individual organizations. But if statistics like those showing up in Clay Lord’s recent graphs, and Elissa Goetschius’s Facebook post are accurate and indicative of the field generally, it would seem that much of the striving is insincere … or the efforts are sincere but ineffective/inadequate … or that we’re striving in vain because we have misidentified the problem … or the goal … or … ???

Growing diversity and the emergence of the cultural hierarchy

In his widely read 1990  book, Highbrow Lowbrow, Lawrence Levine documents the transition in America from the 18th and early 19th centuries—a time when Shakespeare and opera and classical music were popular forms of entertainment enjoyed, re-purposed, and performed by, for, and at the will of the people alongside jugglers, animal tricks, and Yankee Doodle Dandy—to the late 19th and early 20th centuries when cultural hierarchies emerged as a tool for not only defining the “highbrow†arts and segregating them from the “lowbrow” arts (a/k/a “popular”, which became a derogatory term) but defining the “cultural elite†and segregating them from the rest of society. While this history is understood by many in the arts sector, I feel compelled to revisit it in light of the topic of this blog.

Describing the fragmentation and subsequent loss of a shared public culture in the late 19th century, Levine writes:

Theaters, opera houses, museums, auditoriums that had once housed mixed crowds of people experiencing an eclectic blend of their expressive culture were increasingly filtering their clientele and their programs so that less and less could one find audiences that cut across the social and economic spectrum enjoying an expressive culture which blended together mixed elements of what we would today call, high, low, and folk culture. (P. 208)

What was motivating this shift? Levine tells us:

It was not merely the audiences in the opera houses, theaters, symphonic halls, museums, and parks that they [they champions of culture] strove to transform; it was the entire society. They were convinced that maintaining and disseminating pure art, music, literature, and drama would create a force for moral order and help to halt the chaos threatening to envelop the nation. (P. 200)

The “chaos†to which Levine refers related (in large part) to the arrival of new immigrants that “made an already heterogeneous people look positively homogeneous.â€Â Culture was increasingly portrayed as both a force with which to “transform the American people” and as an “oasis of refuge from and a barrier against them.”

Related to (and perhaps stemming from) these contradictory messages, the more people were told that “the arts” were a certain kind of fare for a certain kind of people, (that is, the more they were told that art was serious and sacred and required education and civilized behavior to be appreciated), the more they felt disqualified (and disinterested) to participate. Hence the emergence of two worlds—a cultural gulf, in the words of Levine—moving in opposite directions, each less accepting and understanding of the other over time.

Sound familiar?

While the mid-20th century brought challenges to the cultural hierarchy in America and renewed (and sometimes even sincere) efforts to integrate, diversify, and democratize the arts, Levine suggests that by the close of the 20th century not much progress had been made. In the epilogue to his book, he offers as evidence the key propositions in Allan Bloom’s 1987 book, The Closing of the American Mind. Describing views of Bloom (and others—Levine notes that Bloom is not a lone voice), he writes:

There is, finally, the same sense [as existed at the close of the 19th century] that culture is something created by the few for the few, threatened by the many, and imperiled by democracy; the conviction that culture cannot come from the young, the inexperienced, the untutored, the marginal; the belief that culture is finite and fixed, defined and measured, complex and difficult to access, recognizable only by those trained to recognized it, comprehensible only to those qualified to comprehend it. (P. 252)

The emergence of a cultural hierarchy in the early 20th century was a tool for social and ethnic exclusion and from its inception this segregation was led by wealthy individuals in society—at the time, white people, often men. The production of high art may have required patrons (productions costs rose while the patron base shrunk); but, more importantly, patrons demanded that the worlds of high and low art be separated.

I wish I could say that this does not still feel like “the natural state†for the arts in the US.

Disrupting the hierarchy

A few years back Clay Lord interviewed me about the work on intrinsic impacts that Theatre Bay Area and Alan Brown were doing (which, as I understand it, found that a production at a small community theater in the upper Midwest had greater intrinsic impact on its audiences than any production by a professional theater in the study). At one point I said that I hoped their work could “help reframe the conversation about social value and about what it means to be a leading organization.†I asked Clay:

Can we somehow use these new metrics to help us see the world [differently]? … Who’s at the top? Who’s at the bottom? Who’s considered leading? These are rankings that were established decades ago and it’s nearly impossible for even an incredibly worthy and high-performing entrant to displace one of the ‘pioneering’ incumbent organizations at the top of the pyramid. We need data that can help us see the field differently.

Well, it would appear the Irvine Foundation has collected it. Moreover, armed with data and having gained a new understanding of the culture sector in its region, Irvine appears to be attempting to invert (or flatten?) the cultural hierarchy. (That’s my read, at any rate.) Its new strategy is to fund organizations/programs that use hands-on participation to engage nontraditional audiences ahead of (or alongside?) organizations/programs designed primarily to provide passive entertainment for those already inclined to participate. (It’s hard to tell from what’s been written whether the new strategy is intended to complement or displace the old one.)

Understandably, this shift has been a bit of a jolt to the cultural sector of the region. As Nina Simon reported on her blog, the move has been characterized as being “ahead of the field” and has not been embraced by as many arts organizations as Irvine hoped or expected. Throughout its process Irvine has welcomed input and has responded graciously to questions and critiques.

The critical response to Irvine’s new program is telling. Irvine’s new strategy is backed by solid research. As I’ve noted elsewhere, it’s not a capricious move. This strategy is more thoughtfully conceived than many funding strategies to hit the arts sector in the past several years.

So, what’s the problem?

Irvine is disrupting the status quo.

The reason it’s difficult for even incredibly worthy newcomers to rise in our sector is because incumbents continue to be privileged by the system. Over and over again we see rewards (fame, status, economic advantage) accruing to a small number of already established leading organizations—what Robert Merton in 1968 coined the Matthew effect, a term taken from a verse in the bible:

For unto every one that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance: but from him that hath not shall be taken even that which he hath.

Even when foundations attempt to support diversity somehow old, large, and largely white, professional institutions seem to benefit. When philanthropists give money to flagship resident theaters to do black plays instead of giving money to small black theaters to simply stay in business they may do so in a sincere attempt to encourage diversity in largely white theaters but what they legitimize is not “diversity†but rather “white theaters.â€

And legitimacy cuts both ways. It’s hard to legitimize professionals without making amateurs illegitimate. It’s hard to legitimize large resident theaters without making every other kind of theater (e.g., ensemble theaters, ethnically specific theaters, community-based theaters, grassroots theaters) seem less legitimate.

Let’s stop talking about diversity and talk instead about equality … and policy

Of the many posts contributing to the Irvine/Diversity Funding discussion over the past month, I found myself returning to one by Linda Essig. Inspired by having heard urban theorist and former mayor of Bogotá Enrique Peñalosa speak about his vision for more sustainable and egalitarian cities, Linda wrote a post asking whether it was time for us to stop talking about diversity in the arts and talk instead about equality.

She writes:

One of the basic concepts he [Peñalosa] espouses is that in an egalitarian society, because every bus rider is equal to every car driver, a bus with eighty passengers should be given eighty times the road space of car with a single driver.  Further, bicycles in motion should be given higher priority than cars that are parked. In Bogotá, this meant dedicated bus lanes; it meant bike lanes protected from automobile traffic by a median for parked cars; it meant bike lanes and sidewalks were paved before parking lanes.

Linda then extends the metaphor to a discussion of diversity in the arts asking, for instance, whether we are giving equal attention, space, and opportunity to non-Greco-Euro-Anglo art forms. Reframing this diversity discussion in terms of equality resonates for me.

Awhile back I wrote a post on the extraordinarily high quality of the school system in Finland, which differs from the US education system in several ways, one of which is its focus on social equity rather than excellence.  The policy of Finland: “Every child should have exactly the same opportunity to learn, regardless of family background, income, or geographic location.†Education is seen not as way to produce star performers but as a way to achieve social equity.

Likewise the revered Venezuelan social program, El Sistema, which puts instruments in the hands of hundreds of thousands of children. Both programs demonstrate that excellence and equity need not be at odds. Finland has a far superior education system to the US public education system. El Sistema created Dudamel and many other talented musicians.

At the end of the post on Finland’s education system, I asked:

In ten or twenty more years does the nonprofit arts and culture sector want to be the US education system: excellent art for rich people and mediocrity, lack of resources, and lack of opportunity for everyone else? Or do we want to be Finland’s: high quality artistic experiences (or ‘an expressive life’ as Bill Ivey might say) for every man, woman, and child?

We always say that the US has no cultural policy, but is this true? Or is our implicit policy the one that was set by elites at the turn of the last century and served their social goals at the time? Moreover, is it possible that our resistance to creating a national cultural policy has become a method for maintaining those goals?

Late-19th-century policies and practices transformed the US cultural sphere and resulted in the loss of a shared public culture and the disproportional privileging of certain art forms, institutions, and people over others.

Shall this history continue to distort the way we see (and fail to see) our world?

Or shall we make an amendment to our default culture policy?

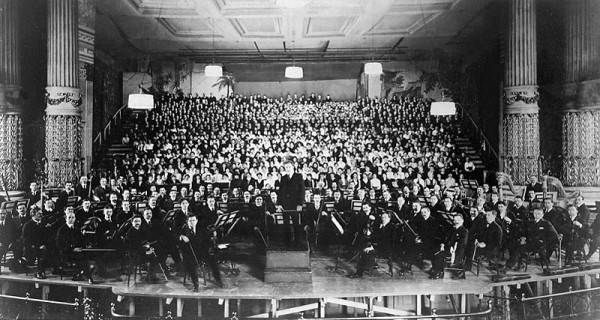

Photo:Â Philadelphia Orchestra, 1916

***Â (Leslie Houts Picca and Joe Feagin. 2007. Two-Faced Racism: Whites in the Backstage and Frontstage. New York, NY: Routledge)