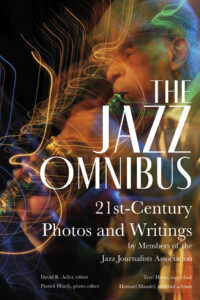

I’m proud of my two published books (Miles Ornette Cecil – Jazz Beyond Jazz and Future Jazz) and my unpublished ones, too; the two iterations of the encyclopedia of jazz and blues; I edited, and my collaborations with some musicians creating their own books — but right now I’m crazy enthusiastic about The Jazz Omnibus: […]

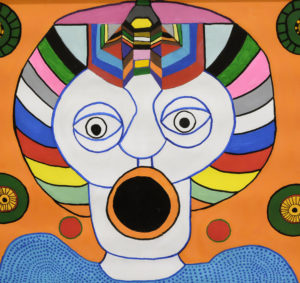

“Supermusician” Roscoe Mitchell’s paintings revealed!

Roscoe Mitchell — internationally renown composer, improviser, ensemble leader, winds and reeds virtuoso who has pioneered the use of “little instruments” and dramatic shifts of sonic scale in the course of becoming a “supermusician . . .someone who moves freely in music, but, of course, with a well established background behind . . .”* reveals […]

Who plays the saxophone? And why?

I love the sound of a saxophone, or rather the broad range of sounds available from this family of reeds instruments. Breathy, vocal-like, smooth, light, penetrating, gritty or greasy, able to cry and/or croon (sometimes both at once), it strikes me as capable of the most personal of musical statements, although that’s probably a projection […]

Listening to Coltrane’s “Ascension,” and what I’ve done. . .

Yesterday’s Concert dropped a podcast in which I offer guidance in listening even to challenging jazz recordings such as John Coltrane’s ambitious, gnarly Ascension. And semi-shameless self-promotion: Music Journalism Insider has published a comprehensive career interview with me. For Todd L. Burns’ invaluable, subscription-supported newsletter/platform about music journalism, I lay out at his request the […]

City of Chicago, music promoter

Lollapalooza 2021 had some 385,000 attendees (without significant Covid-19 outbreak, fortunately) but featured little of host Chicago’s indigenous talent or styles. And that’s just wrong, declared Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events commissioner Mark Kelly, launching the month-long Chicago in Tune “festival” at a reception August 19. Here’s the still-evolving event calendar of hundreds […]

Chicago Jazz Fest expanded review & Deutsch photos

My DownBeat review of the 39th annual Chicago Jazz Festival held over Labor Day weekend in and spilling out of Millennium Park, highlights the best I heard — including the specially organized big band led by trumpeter Jon Faddis, making big fun from his mentor Dizzy Gillespie‘s fresh-as-fire arrangements dating 60 to 70 years back. (Gotta wonder what a […]

Great new jazz photography: Sánta’s faces of Northsea Jazz Fest

The faces of jazz musicians Sánta István Csaba hears, sees and snaps are indelibly expressive — like the memorable phrases, inspired improvisations and magical connections these players play, so meaningful to listeners in the moment, remembered or recorded. JazzTimes magazine has published some of Sánta’s images from the Northsea Jazz Festival in early July — here are […]

Great new jazz photography #2: Lauren Deutsch’s Made in Chicago portfolio

“Made in Chicago” is true of the photography of Lauren Deutsch, and also the name of the four-day-long collaborative jazz festival she’s organized in Poznan, Poland for the past 12 years as artistic director (formerly with Wojceich Juszcsak) on behalf of the Jazz Institute of Chicago. The theme of this year’s fest was “Freedom.” The photos here […]

Patti Smith’s New Year’s Eve vow: “We must not behave!”

Ushering in 2017 with Patti Smith and band at Chicago’s Park West New Year’s Eve was inspiriting for us of a certain age and artsy disposition. Grey-haired but loose and limber — funny, fierce, profane and poetically incantatory — Smith celebrated her 70th birthday in the city of her origin as if for all boomers and our […]

Jazz warms Chi spots: Hot House @ Alhambra Palace, AACM @ Promontory

There are good arguments for building venues just for jazz. But speaking of arts communities in general: Most are moveable feasts, fluid, transient, at best inviting to newcomers to the table. It’s demonstrable that when jazz players and listeners alight at all-purpose spaces such as Chicago’s Alhambra Palace, where Hot House produced the trio of saxophonist David Murray, bassist […]

Chicago’s free summer music cornucopia – Deutsch, PoKempner photos

With a 10th annual Latin Jazz festival produced in the neighborhood Humboldt Park by the Jazz Institute of Chicago and dynamite downtown concerts with headliners such as Nigerian juju star King Sunny Adé and Afro-Cuban progressive Eddie Palmieri put on by DCASE, the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events, Chicago’s free summer music programs […]