There are good arguments for building venues just for jazz. But speaking of arts communities in general: Most are moveable feasts, fluid, transient, at best inviting to newcomers to the table. It’s demonstrable that when jazz players and listeners alight at all-purpose spaces such as Chicago’s Alhambra Palace, where Hot House produced the trio of saxophonist David Murray, bassist […]

Dr. Richard Wang, enabler of AACM experimentalists, RIP

In his first college teaching job at Wilson Junior College during the early 1960s, trumpeter Dick Wang encountered a cadre of exploratory young Chicago musicians who would soon form the AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians). He encouraged them. He introduced Roscoe Mitchell, Joseph Jarman and Malachi Favors, Anthony Braxton, Henry Threadgill, Ari Brown […]

African roots, Middle Eastern extensions in Hyde Park Jazz Fest

Pianist Randy Weston, a magisterial musician at age 90 inspired by jazz traditions and its African basics, and trumpeter Amir ElSaffar, who has devoted himself to incorporating the Middle East’s modal, microtonal maqam legacy into compositions for jazz improvisation by members of his Two Rivers Ensemble, were highlights of last weekend’s 10th annual Hyde Park Jazz Festival. Both […]

Chi jazz fest 2016, details in photos and words

My DownBeat overview of the 38th annual Chicago Jazz Festival, comprehensive as I could make it, didn’t go into depth on any of the couple dozen performances I heard from Sept 1 through 4 in downtown Millennium Park and the Cultural Center. So here, with imagery by my photojournalist colleagues and friends Marc PoKempner and Michael Jackson (whose photo […]

Thomas Chapin on film, with TromBari in Normal IL

Glenn Wilson, a terrific baritone saxophonist and flutist based in Normal, IL, is also a major mensch. Last Saturday, at the end of Normal’s Sweet Corn and Blues festival, he organized a free concert and screening of Thomas Chapin: Night Bird Song, a comprehensive documentary about his friend, the usually exuberant alto saxophonist, flutist and composer who died of leukemia […]

A Great Migration suite from trumpeter Orbert Davis: Audio interview

Orbert Davis — trumpeter, composer and leader of the Chicago Jazz Philharmonic, has been commissioned by the Jazz Institute of Chicago to write and perform a suite about the Great Migration for the 38th annual free Chicago Jazz Festival. “Soul Migration,” for octet, will be heard Sept 1 at 8 pm in Millennium Park’s Pritzker Pavillion. […]

MCA-Chicago’s Terrace concerts, acing outdoor presentation

Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art has aced outdoor music presentations with its Tuesdays on the Terrace series, most recently featuring the string trio Hear In Now performing strong yet sensitive chamber jazz. Drawing a thoroughly diversified crowd to enjoy fresh, creative music in open space on a summer afternoon for free (food and beverages extra) shouldn’t be […]

Gospel (not my usual bag) keyboards revelations

I’ll never be an avid fan, much less an aficionado, of gospel music — but Lift Me Up, Chicago Gospel Keyboard Masters, new from The Sirens, a local independent label, is clearly full of joy and inspiration. It also is notable for documenting a seldom spot-lit but obviously thriving American roots music scene. Art arising from or meant to beget religious transcendence […]

Chicago’s free summer music cornucopia – Deutsch, PoKempner photos

With a 10th annual Latin Jazz festival produced in the neighborhood Humboldt Park by the Jazz Institute of Chicago and dynamite downtown concerts with headliners such as Nigerian juju star King Sunny Adé and Afro-Cuban progressive Eddie Palmieri put on by DCASE, the city’s Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events, Chicago’s free summer music programs […]

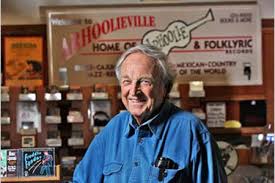

Arhoolie Records (a dozen faves) to Smithsonian

Excellent news on the archival recordings front: Arhoolie Records, the 55-year old treasury of American folk and vernacular musics, has been acquired by Smithsonian Folkways, the non-profit record label of the Smithsonian Institution. So a broad, odd, historic, incomparable cultural catalog, founded and run since 1960 by producer Chris Strachwitz (now 84) enters the public trust. Smithsonian […]

Historic days for US and Cuba, accompanied by jazz

Congratulations to the U.S. and Cuba for advancing our long overdue reset. It’s about time. Jazz at its best has linked our nations for decades, through the tangled history of corrupt dictatorship and revolution, missile crisis, failed invasion, bad relations and trade embargo — and in this recent historic moment, Afro-Cuban-American music is exploding with exciting new recordings. A hint of accords and collaborations […]

Ornette Day, bits of wisdom with video clips

Ornette Coleman’s birthday is today, and his son Denardo has invited everyone to a walk with him from noon to three in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx, where his father, the prophet of Harmolodics, is interred near Duke Ellington, Miles Davis, Max Roach, Celia Cruz — a very good neighborhood. In Ornette’s honor here are excerpts of […]

Chicagoans’ albums reviewed, author’s edition

My reviews of recordings  by Chicago pianists Larry Novak, Laurence Hobgood and Robert Irving III, percussionist Art “Turk” Burton, and saxophonists Caroline Davis and Roy McGrath appeared in DownBeat‘s January issue, but the print edition limited their length. DB’s rating system ranges from one to five stars (*s), poor to masterpiece. Here’s my text as […]