Jane Fonda and other Hollywood stars are modeling their battle against the Trump regime’s “campaign to silence critics” on the Committee for the First Amendment, which was initially formed during the “Red Scare” of the 1940s.

Here’s what happened the first time around.

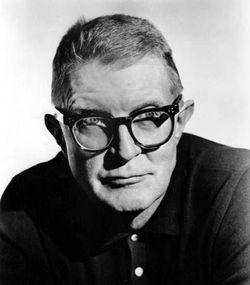

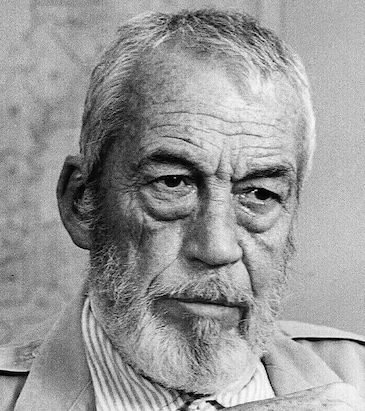

In late September 1947, more than forty people working in the movie industry received subpoenas to appear before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, headed by J. Parnell Thomas. He was about to convene a congressional hearing in Washington, D.C., on “alleged subversive influence in motion pictures.” Within days William Wyler met with two old friends, John Huston and the screenwriter Philip Dunne, as well as Alexander Knox, a prominent Canadian character actor. The four decided to rally opposition to the hearing. They called their campaign “Hollywood Fights Back,” soon after known as the Committee for the First Amendment.

“Our first meeting was at Lucey’s,” Dunne told me. “It was a restaurant across from the RKO and Paramount studios. I called the meeting. I talked it over with Willy first. It was Willy who called John in on it. [Huston was an officer in the Screen Directors Guild.] Alex began making phone calls. The thing snowballed. The next meeting, the big meeting, was at Ira Gershwin’s house. He had a large house and the place was packed. We changed the name of our group to the Committee for the First Amendment because we believed the ‘unfriendly’ witnesses who’d been subpoenaed would adopt a clear-cut constitutional defense.”

J. Parnell Thomas, the HUAC chairman, was a tiny, pink-faced Republican congressman from New Jersey who craved headlines and believed the easiest way to get them would be to attack the film industry. He had been out to Los Angeles five months earlier in May and had taken secret testimony at the Biltmore Hotel from fourteen so-called “friendly” witnesses. Thomas and HUAC’s chief investigator Robert E. Stripling briefed the press daily on what had been said behind closed doors.

Lela Rogers, Ginger’s mother, reportedly testified that she believed writers Dalton Trumbo and Clifford Odets were Communists. Her daughter, she said, had declined to utter a line (“Share and share alike, that’s democracy”) in one of Trumbo’s screenplays. The actor Adolph Menjou had called Hollywood “one of the main centers of Communist activity in America.” The infiltration of Hollywood by subversive elements, according to Thomas, had resulted in “flagrant Communist propaganda films,” among them Song of Russia, Tender Comrade, and The Best Years of Our Lives. This cried out for exposure. Among others who gave secret testimony were actors Robert Taylor and Gary Cooper and, reluctantly, Warner Bros. production chief Jack L. Warner.

With HUAC’s Washington hearings scheduled to begin October 20, 1947, the Committee for the First Amendment that convened at Gershwin’s house was in a defiant mood. The huge crowd of top stars that gathered that night included Edward G. Robinson, Danny Kaye, Judy Garland, Gene Kelly, Humphrey Bogart, Lauren Bacall, Burt Lancaster, Evelyn Keyes, Sterling Hayden, Jane Wyatt, Marsha Hunt, John Garfield, Henry Fonda, Ava Gardner, Myrna Loy, Gregory Peck, Paulette Goddard, and Katherine Hepburn. They prepared a declaration, went public with it several days later in full-page newspaper ads across the country and presented it to Congress in the form of a petition.

“We the undersigned, as American citizens who believe in constitutional democratic government, are disgusted and outraged by the continuing attempt of [HUAC] to smear the Motion Picture Industry,” it said. “We hold that these hearings are morally wrong because: Any investigation into the political beliefs of the individuals is contrary to the basic principles of our democracy; any attempt to curb freedom of expression and to set arbitrary standards of Americanism is in itself disloyal to both the spirit and the letter of the Constitution.”

During the meeting prearranged phone calls came from Washington with an update on the latest HUAC developments. After further discussion, the Committee for the First Amendment decided to send a delegation to the hearings as a further show of support. They chartered a TWA Constellation from Howard Hughes for thirteen thousand dollars. The tycoon “had no interest” in the protest, Huston told the press. “It was strictly a business deal.” The plane was called, by an unfortunate coincidence, Star of the Red Sea.

According to Dunne, the CFA founders retained control of the ad hoc group with the help of an informal steering committee: director Anatole Litvak, screenwriter Julius Epstein, actor Sheppard Strudwick, producers Joseph Sistrom (a conservative Republican) and David Hopkins (the son of FDR confidant Harry Hopkins). Volunteers recruited for the flight to Washington included many of the stars who had gathered at Gershwin’s. Wyler wanted to go but was advised by his doctors not to fly. “Originally Huston was going to go alone, without the two of us,” Dunne recounted. “But he called me in the middle of the night and said, ‘You’re not going to leave me with this bunch of maniacs.’ So the two of us went, and Willy stayed behind. We wanted someone to run things, anyway, while we were gone.”

The night before the October 26 flight, Wyler called a meeting at Chasen’s restaurant and reminded the delegation that they were likely to come under political attack. According to Dunne, Wyler cautioned, “If anyone aboard the plane is in the slightest degree vulnerable, our entire group and its cause could be discredited. If there is anything in any of your pasts that could hurt you or us, don’t’ go. You don’t have to tell us about it. Just don’t show up at the airport tomorrow morning.”

(Lauren Bacall remembers this warning rather differently: “Wyler told us we must not look like slobs. We were representing a lot of people in the industry, we must make a good impression — the women were to wear skirts, not slacks; the men, shirts and ties.”)

Wyler himself has recounted that he told the delegation to maintain a distance from the unfriendly witnesses. “I told them that the newspapers would say they were there to defend the Communists, but that they were going to Washington to attack the House Un-American Activities Committee and not to defend any Communists.”

The distinction later became a matter of controversy. Detractors of the CFA would claim that its stance ultimately betrayed the unfriendly witnesses by seeming to equivocate. Why wouldn’t the CFA stand up for Communists if it believed that citizens in a democracy had a right to their political beliefs? Defenders of the CFA would claim that the unfriendly witnesses themselves had muddied the constitutional waters by engaging in a vociferous debate with HUAC. Instead of declining to answer questions on the grounds of their First Amendment rights, many chose to answer some questions but not others. According to Dunne, that was a misguided attempt to defend themselves with self-righteous pronouncements.

“We had two specific goals,” Dunne recalled in his autobiography. “First, we timed our flight to Washington to support the scheduled testimony of Eric Johnston, the [president and] spokesman for the [Motion Picture] Production Association, who had publicly declared that the motion picture companies would never impose a blacklist nor submit to censorship. Second, we intended to confront Richard Nixon, the only congressman on the House Committee from our home state, and request that he either call off the hearings or insist on a reformation of its procedures.”

— from A Talent for Trouble).

To read what happened next, click here.

For anyone who hasn’t yet, this is an ideal time to read A TALENT FOR TROUBLE. One of my favorite books about Hollywood. A good time to RE-read it too.

Hi George. Nice surprise.! Thanks.for that.

I remember seeing you in Berkeley when the book came out.