Lollapalooza 2021 had some 385,000 attendees (without significant Covid-19 outbreak, fortunately) but featured little of host Chicago’s indigenous talent or styles. And that’s just wrong, declared Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events commissioner Mark Kelly, launching the month-long Chicago in Tune “festival” at a reception August 19. Here’s the still-evolving event calendar of hundreds […]

Tania Leon interview 1989

Tania Leon, 2021 winner of the Pulitzer Prize for music composition, has not often been interviewed in the popular press, so here’s a Q&A I conducted with her as published in 1989 by Ear magazine, and Jeremy Robins’ 2007 Composers Portrait of her, commissioned by American Composers Orchestra. Tania Leon, Assistant conductor of the Brooklyn […]

Boogie-man Helfer bounces back from covid-depression

Erwin Helfer, the 84-year-young Chicago pianist of heartfelt blues, boogie, rootsy American swing and utterly personal compositions, has told his tale of covid-19-related profound depression, hospitalization, treatment and recovery to the Chicago Sun Times. I’m a longtime friend, ardent fan and two-time record producer of Erwin’s, and had lunch with him soon after the article […]

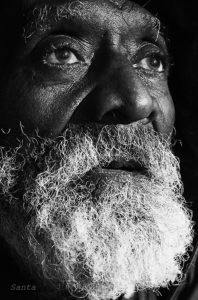

Revered jazz elders, deceased: portraits by Sánta István Csaba

As a generation of jazz elders leaves our world — some hastened by the pandemic — their faces as photographed by Sánta István Csaba become even more luminous, haunting, iconic. Originally from Transylvania and currently living in Turin, the northern Italian area with heaviest covid-19 infections, Sánta reports that he is healthy, employed at the […]

JazzOnLockdown: Musicians, venues, .orgs — writers? — turn to live-streaming

It’s the most obvious, available and so far low-cost option for anyone who can cast a performance online for public consumption — jazz musicians specifically included: Live-streaming. Fred Hersch has been first out of the box, committing to live-streaming daily mini concerts from his living room, 1pm Eastern Daily Time (10am PST, 7pm in Europe) […]

Jazz vs. lockdown: Blogs w/ vid clips defy virus muting musicians

Jazz doesn’t want to stay home and chill — so members of the Jazz Journalists Association launched on Monday, 3/15/2020, JazzOnLockdown: Hear It Here, a series of curated v-logs featuring performance videos of musicians whose gigs have been postponed or cancelled due to coronavirus concerns. The initial JOL post, by Madrid blogger Mirian Arbalejo (of […]

Mardi Gras’ lewd Krewe, Marc Pokempner’s photos

Satirical, scatalogical New Orleans parade floats by Krewe du Vieux Carré, via photojournalist Marc PoKempner

Chicago Jazz fest images, echoes

The 41st annual Chicago Jazz Festival has come and gone, as I reported for DownBeat.com in quick turnaround. I stand by my lead that the music was epic — cf. Marc PoKempner‘s beautiful image of the Art Ensemble of Chicago at Pritzker Pavillion, facing east towards Mecca just before their African percussion-driven orchestral set. And […]

Transcending Toxic Times with street poetry & music

My DownBeat article about Transcending Toxic Times, the compulsively listenable, critically political album by the Last Poets produced by electric bassist/composer Jamaaladeen Tacuma, includes a lot of quotes from my interviews with him and poet Abiudon Oyewale. I reproduced some of the searing imagery/lyrics on the recording, and provided background on how these men have […]

Digging Our Roots videos, speakers inspire engagement

Musicians and journos with insights into historic hits can offer curious audiences low-cost interactive experiences that bond most everybody present, like any successful performance.

Audio-video jazz improv: Mn’Jam Experiment, w/teens

What’s really new in improvisational music? Where else can innovation go? Mn’JAM Experiment — singer Melissa Oliveira and her visual/electronics/turntablist partner JAM — are daring to mix high-tech audio-with-video media in live performance, and as they say, it’s an experiment, in a direction that live performance seems sure to go. Grounded in jazz fundamentals (call […]

2018 jazz, blues and beyond deaths w/ links

Not a happy post, but a useful one: here are the hundreds of musicians and music industry activists who died in 2018, as compiled by photographer-writer Ken Franckling for the Jazz Journalists Association. Ken scoured local newspapers, the Jazzinstitut Darmstadt newsletter, AllAboutJazz.com, Wikipedia, the New York Times, Legacy.com, Rolling Stone, Variety, JazzTimes.com, blogs, listserves, Facebook pages and […]

Legacies of Music Makers

The deaths of multi-instrumentalist Joseph Jarman, best known as the face-painted shaman of the Art Ensemble of Chicago, and Alvin Fielder, re-conceptualizing drummer, remind us that artists’ contributions to music extend beyond recordings and awards. Read my essay at NPR Music, commissioned by Nate Chinen of WBGO, on the enduring legacies of Jarman and Fielder, […]