It must mean something that the highest creative achievement in American classical music is permanently controversial. When Porgy and Bess premiered on Broadway in 1935, a typical critical reaction was: “What is it?” American-born classical musicians (unlike their European-born brethren) marginalized George Gershwin as an interloper, a gifted dilettante. Later, in the 1950s, Porgy and Bess was widely criticized for “stereotyping” African-Americans. But this is a decade during which Porgy and Bess was not much seen, excepting a mis-cast, misconceived Hollywood version mangled by Samuel Goldwyn as a labor of love. Beginning in the 1970s, it belatedly entered the mainstream operatic repertoire – yet still excited discomfort (but not among singers who actually sang it).

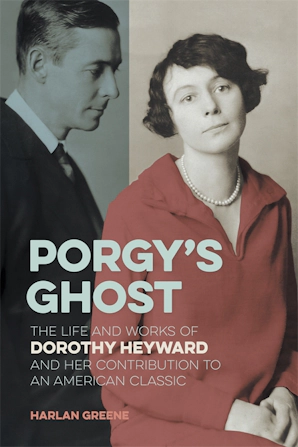

Not the least controversial aspect of Porgy and Bess remains: who created it? The Gershwin Estate mandates that all performances be billed “The Gershwins’ Porgy and Bess.” But that’s not right. First there was the 1925 novel Porgy – a glimpse of Carolina’s creole Gullah culture. It was written by DuBose Heyward, a genteel southerner whose curious arms-length view of the Gullahs was part cultural anthropology, part awed mythology. Then came the 1927 play Porgy, until now attributed to Heyward and his wife Dorothy; its success, however, was partly due to the machinations of its 29-year-old immigrant director, Rouben Mamoulian. Mamoulian’s elaborately stylized production, which spurned verisimilitude, was packed with music. Then Gershwin turned Porgy into an opera, also Mamoulian-directed, whose libretto closely followed the script of the play. The lyrics for its songs were mostly composed by DuBose Heyward, with an assist from Ira Gershwin. Thanks to Harlan Greene’s beautiful new biography – Porgy’s Ghost: The Life and Works of Dorothy Heyward and her Contribution to an American Classic — we now know that the play Porgy was essentially written by Dorothy Heyward. That means that the opera libretto, too, is basically hers.

Beyond correcting attribution, does it matter? Well, yes – because the genealogy of Porgy and Bess helps us understand its content and its tone. As Greene makes abundantly clear, Dorothy was a northerner whose attitude toward Black Americans was more enlightened than her husband’s. DuBose’s novel ends with Porgy drifting into obscurity after Bess has dropped him. Dorothy’s play ends with Porgy exclaiming “Bring my goat!” – he’s going to find her. DuBose’s Porgy is a curiosity, a loser; Dorothy’s attains stature as a cripple made whole, the moral compass of the community. This difference correlates with changes in plot and perspective both numerous and fundamental. Greene writes: “Her play is no longer just a peep over the color wall into an ’exotic’ community . . . The whole trajectory of the piece is changed, uplifted to loftier art and social commentary.” Greene also shows how Dorothy’s modesty, the eager self-abnegation with which she endeavored to ensure that her husband’s contributions to the opera were not overlooked, ultimately backfired. This excruciating tale, whose villains include Goldwyn, the Hollywood agent Swifty Lazar, and Ira’s wife Lee, culminated in Dorothy’s nervous breakdown.

Greene’s empathy for his subject, and the tenacity of his research, are beyond praise. At the same time, his loyalty to Dorothy inescapably colors his view of Ira Gershwin and also of Mamoulian. He regrets that Sporting Life, the snake in the grass who lures Bess away, is handed an irresistible Gershwin/Ira Gershwin song: “It ain’t necessarily so.” For Dorothy, Sporting Life is a darker force. For the Gershwins, for Mamoulian, for John Bubbles who first sang and danced the role, Sporting Life does not lack charm (in later life, criticizing a Los Angeles production, Bubbles insisted that Bess deserved a credible seducer). And Dorothy’s perspective was at odds with the epic showman in Mamoulian, whose template for both play and opera was indebted to his 1926 Rochester production of Maurice Maeterlinck’s Sister Beatrice: a miracle play with music yielding an ecstatic redemptive ending.

The Heywards did not want Mamoulian to direct Porgy and Bess. Gershwin did. These entanglements will never be wholly untangled: the opera’s vicissitudes are baked in, and archival documentation fails to clarify whether late changes to the play in Mamoulian’s hand – crucial changes — are his or Dorothy’s or a combination of both.

In later life, Dorothy’s output notably included Set My People Free (1948), about a free Black man convicted of planning an 1822 slave revolt. But she never wrote another play nearly as successful as Porgy. In Greene’s portrait of a creative woman caught in a man’s world, her failure to adequately assert herself is an ongoing motif. His biography ends: “Dorothy Heyward remains . . . the ghostwriter of the opera who flits past the audience to haunt Porgy and Bess. . . Her specter is present whenever the curtain goes up, and it is most especially present when it goes down on the transcendent ending she crafted for it, an ending so vastly different from the self-effacing one she fashioned for herself. But that, in the end, is how she wanted it.”

My pertinent book is “‘On My Way’ — The Untold Story of Rouben Mamoulian, George Gershwin, and ‘Porgy and Bess.'”

For a pertinent blog linking to my NPR show arguing that it’s OK for white baritones to sing Porgy, click here.

Thank you for sharing this, and for spotlighting Mr. Greene’s work. The “The Gershwin’s Porgy and Bess” billing appalled me at first, and I still can’t accept it. On the Summer Time -or- Summertime sheet music, it was “lyric by DuBose Heyward” for decades; then that changed too. Ira Gershwin was pleased and fully supportive of the streamlined, trim-the-recitatives 1942 production—–and he found the movie “quite beautiful,” just as Kay Swift said “this is the way George would have loved to see it.” It’s all complicated, isn’t it?

Only a handful of years ’til Public Domain catches up to the opera in the U.S.,, which I look forward to.

I was fortunate to see a wonderful production at Radio City Music Hall. It was glorious. Not burdened by operatic connotations, but fully voiced and acted as if a Broadway production with the finest voices.

Doesn’t anything by Ives count?