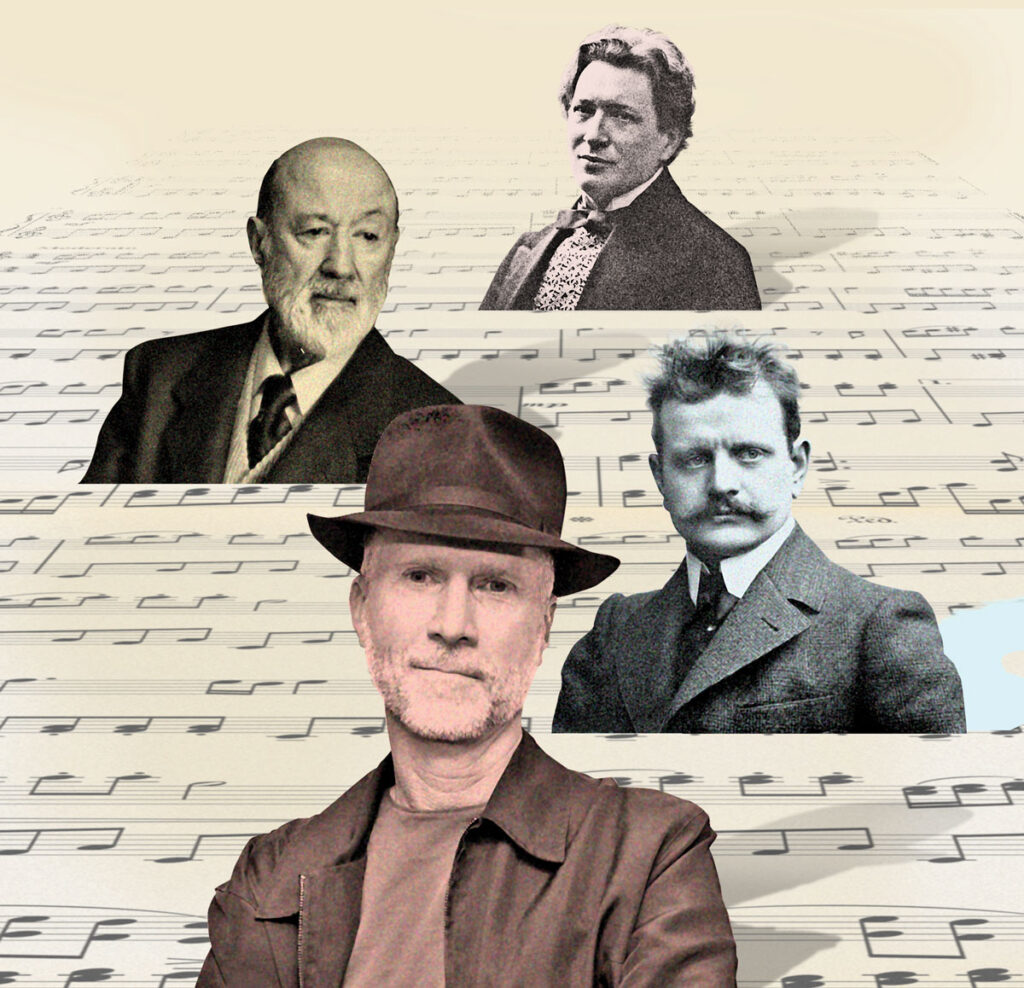

The current issue of The American Scholar includes a long piece of mine suggesting a possible new direction for contemporary classical music – versus the “makeshift music” that deluges our concert halls. I make reference to John Luther Adams, Charles Ives, Jean Sibelius, and Ferruccio Busoni. To read the whole piece, click here. To sample it, read on:

The American arts are receding and blurring. Cultural memory—a prerequisite—is fast disappearing. American orchestras, espousing the new, privilege a surfeit of makeshift eclectic music dangerously eschewing lineage. American opera companies flaunt new American operas that are here today and gone tomorrow. What is needed is an informed quest for orientation, for future direction.

The Italian-born composer-pianist Ferruccio Busoni was a clairvoyant who will never cease to magnetize a coterie of adherents. In his Sketch of a New Esthetic of Music (1907), Busoni proposed the notion of “Ur-Musik.” It is an elemental realm of absolute music in which composers have approached the “true nature of music” by discarding traditional templates. Sonata form, since the times of Haydn and Mozart a basic organizing principle governed by goal-directed harmonies, would be no more.

Half a century ago, Ur-Musik could be written off as a faint footnote to twin seminal 20th-century currents: Igor Stravinsky’s neoclassicism and Arnold Schoenberg’s serial rigor. But no longer. John Luther Adams, among the most esteemed present-day American composers for orchestra, embraces something like it. And his forebears include composers of renewed consequence: Jean Sibelius in his primordial tone poem Tapiola (1926) and Charles Ives in his unfinished Universe Symphony (begun in 1915).

Around the same time, before locking on his 12-tone rows, Schoenberg experimented with an unmoored nontonal style. He was concurrently corresponding with Busoni, who also conferred with Sibelius. In an email exchange, I learned from Adams that, while composing his Pulitzer Prize–winning Become Ocean (2013), “the only music I was listening to was Tapiola.” I brought up Ives’s Universe Symphony and suggested that Adams was “post-Ivesian.” He readily agreed. So there are dots—big ones—to connect.

Might there not be lineage here?

For much more on Busoni, click here.

You ask the big question about an orientation, a future direction, a way forward. The question has loomed over our musical culture, unanswered, ever since the serialist revolution. In an American context, I wonder what role you see for the composers of our African-American heritage: Still, Price, Burleigh, Dawson; Ellington, Strayhorn, Williams, Johnson; Monk, Parker, Davis, Mingus, Coltrane; Tristano, Brubeck, Evans (both Bill and Gil). Are Armstrong’s Hot Fives and Hot Sevens the foundation for one kind of American chamber music? As to a music that composes itself, what of Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, Keith Jarrett? Is there potential in a 21st-century Third Stream integration that brings all these strands together? As to Strayhorn specifically, Walter van de Leur, in his book Something to Live For, shows that Strayhorn’s harmonic and melodic language was in several ways quite close to Bartok’s axis system as described in Ernő Lendvai’s book on Bartok’s compositional methods, but independently developed. The music of the future is still to be created…