My latest installment of “More than Music” on NPR explores racial attitudes in Boston and New York at the turn of the twentieth century. During Antonin Dvorak’s historic American sojourn (1892-95), he was classified by Boston’s music critics as a “Slav” – a rung below Anglo-Saxons like Beethoven. The leading Boston critic, Philip Hale, also called Dvorak a “negrophile” and decried his influence on Boston’s leading composer, George Chadwick. Hale considered African-Americans “barbarians.”

As this line of thought – hierarchizing race – was once ubiquitous, we may be shocked but unsurprised. It is the New York response to Dvorak that is truly surprising. When New York’s critics assessed Dvorak, racial hierarchies were never invoked. In fact, no less than Dvorak when he espoused “Negro melodies,” many New Yorkers looked to Black America for musical instruction and guidance.

It was at Manhattan’s Madison Square Garden Concert Hall that Dvorak led an inter-racial orchestra, an all-Black chorus, and two stellar Black soloists in his arrangement of Stephen Foster’s “Old Folks at Home” in 1894. Three years later, William Randolph Hearst rented the Metropolitan Opera House for a fundraiser featuring the Black vaudeville stars Bert Williams and George Walker alongside excerpts from Aida and Rigoletto. Those events were unthinkable in Boston.

In short: New York was a city of immigrants. In Boston, you were an American if your forebears descended from the Mayflower. My own writings – in particular, comparing Boston and New York in Classical Music in America: A History of Its Rise and Fall (2005) – have long explored the surprising fluidity of race in late Gilded Age New York.

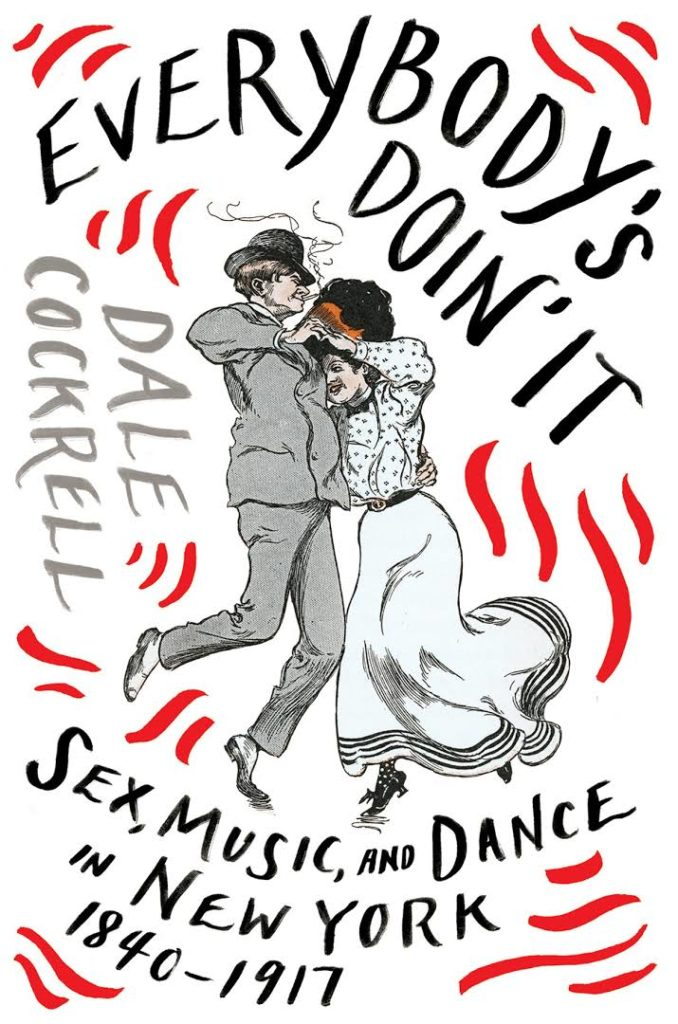

A comparable perspective, also sampled on “A Tale of Two Cities,” is detailed in Dale Cockrell’s remarkable 2019 book, Everybody’s Doin’ It — Sex, Music and Dance in New York: 1840 to 1917. Cockrell’s methodology was to scour the reports of undercover agents working for a well-heeled vigilante group: The Committee of Fourteen. They infiltrated saloons, hotels, dance halls, and brothels. The “disorderly behavior” they successfully terminated was specifically inter-racial: music, dancing, and sex. Segregation set in just after World War I. Harlem’s famous Cotton Club, where Black musicians entertained white audiences, was one result.

“I don’t know where this myth got established,” Cockrell says of Gilded Age stereotypes emphasizing snobbery and privilege. Applied to musical New York, “it’s just wrong.”

As I remark on NPR: “The iconic image is Edith Wharton’s account of going to the opera, in her 1920 novel The Age ofInnocence – a world of snobbery, wealth and fashion. But look again and Wharton is only describing one stratum of the audience at the Academy of Music: the boxholders. We know from other accounts that the Academy’s opera audience was roiling with boisterous Germans and Italians. During intermissions, they would congregate with the singers, amid clouds of cigar smoke and liquor fumes, in a basement lager beer cavern.”

To read my “Wall Street Journal” review of Dale Cockrell’s book, click here.

To read a review of “More than Music” in the Boston Musical Intelligencer, click here.

LISTENING GUIDE (to hear the show, click here):

PART ONE: Dvorak sets “Old Folks at Home” in New York; Music critics hierarchize race in Boston

PART TWO (12:00) : Celebrating Boston’s George Chadwick — “the most maligned and misunderstood American composer.” [Thomas Wilkins leads the Boston Symphony in Chadwick’s Third Symphony at Tanglewood this summer, on July 20.]

PART THREE (29:50) : Boston debates Arthur Nikisch’s Beethoven 5; Dale Cockrell expounds racial fluidity in NYC before WW I

More to the story though… In turn-of-the-century Boston, New England Conservatory was educating several significant African-American musicians—Florence Price and Rosamond Johnson among them.