Jock Soto retires from the New York City Ballet’s stage on June 19 at the age of 40, after 25 years with the company. For the latter part of that period he has been extolled as a partner—as if that were his main (even sole) virtue, as was, essentially, the case with the company’s Conrad Ludlow in the past and Charles Askegard today. Yes, Soto’s an astute, often sublime, partner, but—having been around when he first showed up at the School of American Ballet and set the corridors abuzz with excited whispers: “Have you seen the new boy? Down the hall, taking class. He’s amazing !”—I think back to him as a dancer.

Memory is a tricky thing. Led by sentiment—for an artist’s personality, for the  terrain on which he operated, for the sheer accumulation of history—it can transform dross into gold. So I looked for more concrete evidence of the qualities I remembered in Soto from the early part of his career and found them, where you can see them too, in a videotape of The Magic Flute, choreographed by Peter Martins for the School of American Ballet’s Annual Workshop Performances in 1981. It was right after these performances that Balanchine invited the 16-year-old playing Luke, the male lead, to join the corps of the New York City Ballet.

terrain on which he operated, for the sheer accumulation of history—it can transform dross into gold. So I looked for more concrete evidence of the qualities I remembered in Soto from the early part of his career and found them, where you can see them too, in a videotape of The Magic Flute, choreographed by Peter Martins for the School of American Ballet’s Annual Workshop Performances in 1981. It was right after these performances that Balanchine invited the 16-year-old playing Luke, the male lead, to join the corps of the New York City Ballet.

The ballet itself is a charmer. Like Ashton’s La Fille mal gardée, the model of the genre, it’s a romantic pastoral comedy. Martins adds to the mix a commedia dell’arte element that he no doubt absorbed in his youth from the traditional pantomimes given in Copenhagen’s Tivoli Gardens.

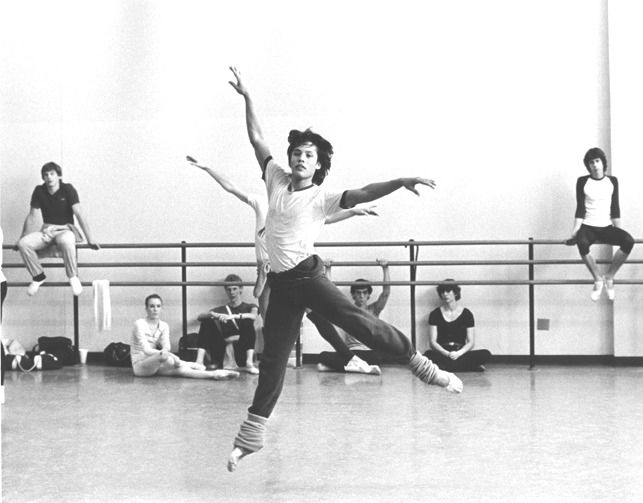

The adolescent Soto recorded here is utterly disarming, and not just because of a frank, luminous smile that is well-nigh irresistible. Of course there are plenty of raw edges in the performance. He’s gawky here and there, unpolished, impetuous, giving himself over to a very simple joy in the moment. You could say he’s only a kid, though no adolescent in serious training for a career in ballet can be simply a kid. Granted, there’s no sign here of the gravitas that would distinguish Soto’s mature work, but the nascent professional is already evident. His placement is very secure and very beautiful. In motion, he’s not merely fluid but also extremely, if casually, graceful. His dancing is consistently soft and floating. On take-offs and landings, his feet seem to caress the floor. (After one lovely solo passage, his fellow students, breaking stage decorum, come out of character and applaud him.) He takes his acting responsibilities seriously and carries them out naturally, as if he’d discovered that Luke had a personality not too far from his own.

The gift for partnering is apparent, too, lacking only the fine-honed skills and increasingly sensitive intuition that experience would bring. Self-confident, Soto exudes a quiet assurance that, vis-à-vis his partner, he will be in the right place in the right way at the right time. Along with this technical aplomb, he displays an easy sympathy toward his lady (the 18-year-old Katrina Killian—tiny, light, and quick) as well as a devotion and respect that might well be termed chivalric. He knows how to frame her, creating an aura around her like a halo, and he knows how to get the hell out of her way. Close-up shots reveal his large, capable hands and strong back. When supported pirouettes are on the agenda, he’s an enabler first class. You can see how, even in these early days, he “roots” his partner, stabilizes her in her most precarious positions and dangerous moves. He’ll stand at a slight distance—waiting, alert, ready—and then simply move in and become her center.

It should be remembered that it was Martins himself who chose Soto to play Luke. Perhaps he recognized the similarity between them as dancers, both in the buoyant, cushioned solo work and the suave partnering. There’s little physical resemblance between them. Martins was tall, blond, Greek-god beautiful. Soto is of medium height, jet-haired and olive skinned, with an Aztec cast to his features. His build is undeniably stocky, with a larger head and shorter neck than classical ballet, obsessed with harmonious proportion, prefers for its princes. Soto’s distinctive anatomy would eventually add to his onstage presence not merely dignity but also intensity, enhancing a key aspect of his temperament—a darkness and ferocity that seized the viewer and refused to let him go.

Now Soto’s audience must let him go, with thanks.

For succinct bios of Jock Soto, along with lists of ballets created for him and the many other roles he danced with the New York City Ballet, use these links:

http://www.nycballet.com/about/print_sotobio.html

http://www.sab.org/faculty_soto.htm

Photo: Steven Caras: Jock Soto, rehearsing Peter Martins’s The Magic Flute for the School of American Ballet’s Annual Workshop Performances, 1981

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

corners of the stage, briefly converges at the center of the space, then moves on (though a pair pauses briefly, side by side), each person simply continuing along the diagonal path prescribed by his or her first step. The ending reiterates this action, which is clearly the simple message of the dance: We exist alone; we meet when we occupy a common space; we interact in passing, our identity left essentially unaltered; we part—because it is only natural that we should.

corners of the stage, briefly converges at the center of the space, then moves on (though a pair pauses briefly, side by side), each person simply continuing along the diagonal path prescribed by his or her first step. The ending reiterates this action, which is clearly the simple message of the dance: We exist alone; we meet when we occupy a common space; we interact in passing, our identity left essentially unaltered; we part—because it is only natural that we should.

Graham’s 1943 Deaths and Entrances, an evocation of the turbulent lives of the Brontë sisters, its emotional climate as roiling as that of Emily’s Wuthering Heights. The piece centers on one of the sisters (originally danced by Graham herself, and whom we can take to be Emily, the one cursed by genius, Charlotte and Anne being merely immensely gifted). This figure works out her terrible conflicts and achieves some sort of ecstatic resolution in a matrix peopled by her sisters, incarnations of their three child selves, rival suitors evocatively called The Dark Beloved and The Poetic Beloved, a pair of auxiliary gentlemen, and an enigmatic collection of props. A transparent goblet, an enormous seashell (the kind that lets you hear the ocean’s implacable waves in the cleft formed by its swollen pink labial folds), and a pair of phallus-like chess pieces are manipulated by the dancers as if they, at least, knew exactly what the objects signified.

Graham’s 1943 Deaths and Entrances, an evocation of the turbulent lives of the Brontë sisters, its emotional climate as roiling as that of Emily’s Wuthering Heights. The piece centers on one of the sisters (originally danced by Graham herself, and whom we can take to be Emily, the one cursed by genius, Charlotte and Anne being merely immensely gifted). This figure works out her terrible conflicts and achieves some sort of ecstatic resolution in a matrix peopled by her sisters, incarnations of their three child selves, rival suitors evocatively called The Dark Beloved and The Poetic Beloved, a pair of auxiliary gentlemen, and an enigmatic collection of props. A transparent goblet, an enormous seashell (the kind that lets you hear the ocean’s implacable waves in the cleft formed by its swollen pink labial folds), and a pair of phallus-like chess pieces are manipulated by the dancers as if they, at least, knew exactly what the objects signified.

Play Without Words takes off from Joseph Losey’s memorable 1963 film The Servant. The ominous screenplay by Harold Pinter tells—in words and even more provocative silences—the black tale of a privileged fellow who hires a “man” (a combination butler-housekeeper-valet) who, playing upon varieties of erotic desire laced with class struggle, proceeds to undo his master. Each of these chaps has a woman in his baggage. Our deplorable/unfortunate hero comes equipped with a fiancée, though neither member of that cold couple has the wits to acknowledge that the gentleman is, at the very least, bisexual. The servant, having made himself indispensable in the household, introduces his “sister” as a maid. The irresistibly provocative miss is, of course, the servant’s bedmate; her real job, to consolidate working-class power by seducing the boss, which she does, ironically, with genuine pleasure.

Play Without Words takes off from Joseph Losey’s memorable 1963 film The Servant. The ominous screenplay by Harold Pinter tells—in words and even more provocative silences—the black tale of a privileged fellow who hires a “man” (a combination butler-housekeeper-valet) who, playing upon varieties of erotic desire laced with class struggle, proceeds to undo his master. Each of these chaps has a woman in his baggage. Our deplorable/unfortunate hero comes equipped with a fiancée, though neither member of that cold couple has the wits to acknowledge that the gentleman is, at the very least, bisexual. The servant, having made himself indispensable in the household, introduces his “sister” as a maid. The irresistibly provocative miss is, of course, the servant’s bedmate; her real job, to consolidate working-class power by seducing the boss, which she does, ironically, with genuine pleasure. wear in George Cukor’s Camille. Executed in black velour, it has a reticent cut—a demure sweetheart neckline, a snugly fitting bodice. From the trim waistline, a generous skirt falls with cushioned weight, extending slightly at the back as if to hint (only hint, mind you) at a train. A spray of black tulle capping the shoulders suggests a pair of wings, the gown’s sole concession to the frivolity of lightness. A modest “brooch” formed from bits of crystal and metal, is anchored dead center on the bosom, like a family heirloom dutifully displayed. But, shooting out a few slender bronze rays, letting fall a sprinkling of minute sparkles that might be stars, it introduces the idea of a celestial universe. This theme expands—explodes, actually—on the skirt, which looks as if a lavish and reckless hand had flung a galaxy across it. The glittering, gleaming incrustation contains clusters of crystals in myriad shapes—squares, rectangles, elongated diamonds, teardrops, five-pointed stars—and graduated sizes. Raised squares and domed circles are emphasized by marcasite-style frames, while flocks of small and even smaller pewter gray sequins create the illusion of stardust. This evocation of a galaxy recalls the work of Schiaparelli’s “Zodiac” collection (with its extravagant beading by the House of Lesage), but where Schiaparelli’s fantasy glories in its ostentation, Adrian’s treatment is more innocent, like something out of a child’s dream.

wear in George Cukor’s Camille. Executed in black velour, it has a reticent cut—a demure sweetheart neckline, a snugly fitting bodice. From the trim waistline, a generous skirt falls with cushioned weight, extending slightly at the back as if to hint (only hint, mind you) at a train. A spray of black tulle capping the shoulders suggests a pair of wings, the gown’s sole concession to the frivolity of lightness. A modest “brooch” formed from bits of crystal and metal, is anchored dead center on the bosom, like a family heirloom dutifully displayed. But, shooting out a few slender bronze rays, letting fall a sprinkling of minute sparkles that might be stars, it introduces the idea of a celestial universe. This theme expands—explodes, actually—on the skirt, which looks as if a lavish and reckless hand had flung a galaxy across it. The glittering, gleaming incrustation contains clusters of crystals in myriad shapes—squares, rectangles, elongated diamonds, teardrops, five-pointed stars—and graduated sizes. Raised squares and domed circles are emphasized by marcasite-style frames, while flocks of small and even smaller pewter gray sequins create the illusion of stardust. This evocation of a galaxy recalls the work of Schiaparelli’s “Zodiac” collection (with its extravagant beading by the House of Lesage), but where Schiaparelli’s fantasy glories in its ostentation, Adrian’s treatment is more innocent, like something out of a child’s dream.