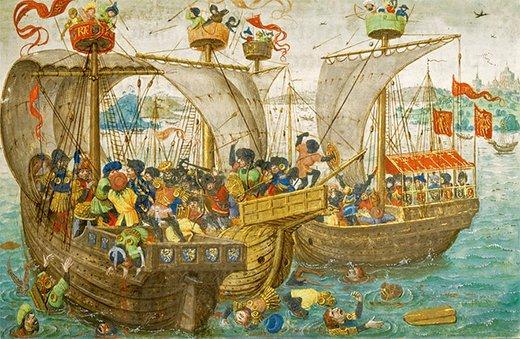

We can quarrel with MoMA’s video game escapade, but everyone’s got to agree that the illuminated manuscript acquired by the Getty museum today is a masterpiece and a beauty. And it makes perfect sense for the Getty’s collection.

The Roman de Gillion de Trazegnies, by Lieven van Lathem (1430–1493), was purchased at Sotheby’s today for nearly $6.2 million. Van Lathem is considered to be the most accomplished painter of secular scenes in the golden era of Flemish manuscript illumination, the museum said.

The Roman de Gillion de Trazegnies, by Lieven van Lathem (1430–1493), was purchased at Sotheby’s today for nearly $6.2 million. Van Lathem is considered to be the most accomplished painter of secular scenes in the golden era of Flemish manuscript illumination, the museum said.

The manuscript consists of “eight brilliantly painted half-page miniatures and forty-four historiated initials” and, as the book was rarely copied. this “romance appears in only three other manuscripts.” The work had been lent to the Getty Museum for its beautiful 2003 exhibition titled Illuminating the Renaissance.Â

According to the Getty’s press release:

The only documented manuscript by Lieven van Lathem, the Prayer Book of Charles the Bold, is already in the Getty Museum’s permanent collection, having been acquired in 1989. This primary work provides the basis for all other Van Lathem attributions. The Roman de Gillion de Trazegnies is regarded as the artist’s preeminent secular work, and this acquisition represents an unrivalled opportunity to unite masterpieces of both secular and devotional illumination by Van Lathem in a single collection.

While this announcement was being made by Timothy Potts, director of the J. Paul Getty Museum, late of the Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge, his replacement was being announced there: it’s Timothy Knox (right), currently the director of Sir John Soane’s Museum* in London. I was just there, and Knox has done a wonderful job of restoring that gem — and I’m far from alone in thinking that.

While this announcement was being made by Timothy Potts, director of the J. Paul Getty Museum, late of the Fitzwilliam Museum at Cambridge, his replacement was being announced there: it’s Timothy Knox (right), currently the director of Sir John Soane’s Museum* in London. I was just there, and Knox has done a wonderful job of restoring that gem — and I’m far from alone in thinking that.

Photo Credits: Courtesy of the Getty (top) and the Soane Museum (bottom)

*I consult to a Foundation that supports the Soane