In an interview given to The Art Newspaper for one of its Frieze editions last week, Nicholas Penny, director of London’s National Gallery, gave his view of a theme I’ve mentioned here once or twice — and went a step further. The topic? The similarity of contemporary art collections in U.S. museums.

Penny, lamenting the influence of the Museum of Modern Art, said:

Penny, lamenting the influence of the Museum of Modern Art, said:

… it has been hugely influential, so that almost all of the other museums in America have a modern wing attached to them. And frankly these wings impress me as deadly: the same white walls with the same loud, large, obvious, instantly recognisable products lined up on them. Nothing in the so-called academic institutions of the 19th century approach them in orthodoxy and predictability.

I agree, and have said so many times. He also took up another lament of mine — the lack of sharp criticism in the art world, saying:

There is a lamentable lack of critical debate about contemporary art. If you think about the way Modern and contemporary art was received in the 19th century, there was always a tremendous amount of critical defence and attack, far more than is the case today

And:

Exhibition in a museum—and, even more so, acquisition—is an endorsement which has become a substitute for critical appraisal. There seems to be a belief that the reputations of artists in museums will never be challenged. This is a valuable myth for the market. It may be that once a certain amount of public money has been invested in art it will be valued forever. But I doubt it.

So naturally, I want to highlight this interview — more of which will be published in the November Art Newspaper — as reinforcement.

Meantime, a hat tip to Charlotte Higgins, writing in the Guardian on Monday, for pointing me to the Penny interview. She focused more on what she called Penny’s “writing off” of performance, video and conceptual art — which is true. For example, he said:

The art form I don’t relate to – I’d put it more strongly actually – is video because it seems to me so often merely to be an incompetent form of film, made with the excuse that it is untainted by the professionalism associated with the entertainment industry. I’m not very impressed by conceptual art nor very often by performance art. I’m uneasy with some aspects of the legacy of Marcel Duchamp.

Agree or not, it’s the debate that’s important — it may well sharpen everyone’s perceptions.

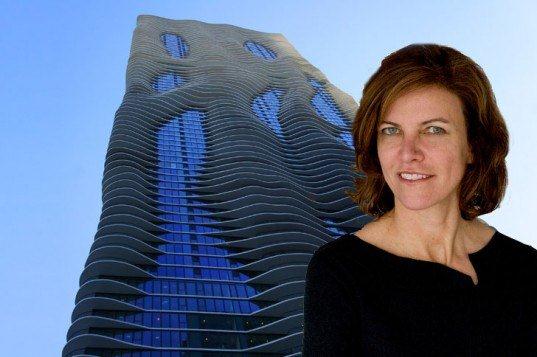

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the National Gallery