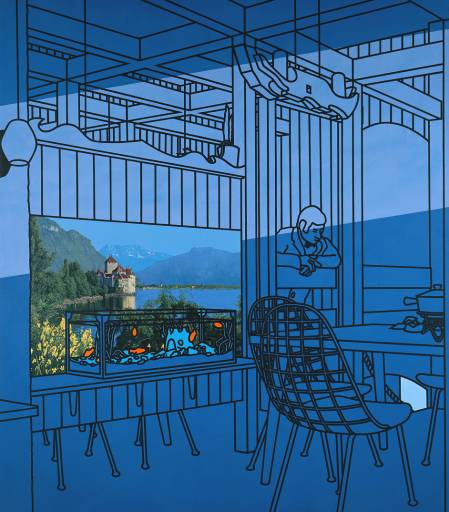

When I last wrote about Richard Koshalek’s plans to build a seasonal blue bubble atop the Hirshhorn Museum — in fall, 2010 — he had disclosed to me a $1 million-plus naming gift from the Bloomberg Foundation as well as his goal of creating a “cultural think tank” that would combine elements of the World Economic Forum at Davos and TED (Technology Entertainment Design) conferences, and thereby insert art into to the national and international dialogue. I laid out those plans and more in a Cultural Conversation with him in the Wall Street Journal. At the time, he needed to raise about $5 million for the bubble, pretty small for a museum addition, despite the expansive if nebulous thinking behind it.

Many people were negative about the idea, however. But Koshalek was sure, and he told me that programming would begin in late 2012, pending his fundraising success.

Many people were negative about the idea, however. But Koshalek was sure, and he told me that programming would begin in late 2012, pending his fundraising success.

Fast forward to now: not much has happened. The new launch date is fall 2014, and according to recent press reports the go or no-go date will occur soon.

Worse, the Inflatable Seasonal Structure, AKA the Bloomberg Bubble, has caused division at the museum. A recent article in Washington City Paper says “Three trustees have left the Hirshhorn’s board of trustees, with rumors of divisions caused by the Bubble following them through the doors of the Gordon Bunshaft–designed concrete donut.”

Ever brash and ebulient, ever more interested in architecture than art, ever ambitious — and those aren’t necessarily critical descriptions — Koshalek is still determined, but the time gap and other considerations (earthquake-proofing, for example) have sent the price tag to something on the order of $11.5 million. It has $4 million, plus another $4 million from the Smithsonian itself for programming, which doesn’t count against the capital cost.

The City Paper article suggests that trustee are worried about the costs of staffing the Bubble, though Koshalek basically shoots that down. I’d guess they are more leary about the very concept of the museum-as-policy-think-tank. From the beginning, Koshalek has never been able to articulate why the dialogue he seeks to start there would matter. It might be educational, as he argues, but would it change anything or be another elitist boondoggle?

The Washington Post, cited by City Paper, has covered the Hirshhorn developments here, Â here, and here. I remember the first, disclosing that board chair J. Tomilson Hill had resigned, but did not see the others, about the Bubble’s fate.

If I had to guess now, I’d say it’s over. It’s pretty hard to pull that much money out of a hat in a couple of months, especially when the structure has already been named.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the Hirshhorn