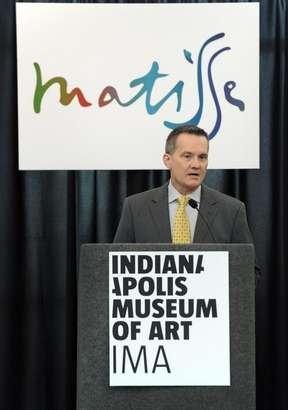

When Charles Venable got the job as director of the Indianapolis Museum of Art last August, I thought it would be a good thing. Now I am not so sure.

Venable came from the Speed Museum, where he had done several things of which I approved — mounting a series of one-painting (masterpiece) exhibitions, for example, and launching a comprehensive review of the Speed’s permanent collection.

Venable came from the Speed Museum, where he had done several things of which I approved — mounting a series of one-painting (masterpiece) exhibitions, for example, and launching a comprehensive review of the Speed’s permanent collection.

But a recent article in The Indianpolis Star has me rethinking; was I fooled, has Venable changed his spots, or is he obeying a board that has its priorities in the wrong order?

The Star article shows Venable to be more concerned about money than about art and quality. It begins this way:

Charles Venable, the new director at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, envisions a giant car show — right there in the museum — an automobiles-as-art thing. Picture super high-end rides like Bugattis. Maybe it’s timed to coincide with an Indianapolis 500.

People would come, Venable is certain of that. They would come in the hundreds of thousands.

Customers. Dollars. Please exit-through-gift-shop. Cha-ching.

An art museum may be a place of beauty and truth and inspiration and epiphanies.

But it’s also about money.

Later it says:

In an interview with The Star, he voiced his displeasure at a recent exhibit of Islamic art because it drew 7,000 people but cost $500,000 to stage. He talked about the importance of packing the house.

After mentioning a coming Matisse exhibition, the article continues:

He sees the Matisse exhibit as the first of many blockbuster shows.

He plans to meet soon with Ken Gross, curator of last summer’s “Speed: The Art of the Performance Automobile†at the Utah Museum of Fine Arts. A highlight of the exhibit was a public chat between Gross and talk-show host Jay Leno, a noted car collector; museum patrons ponied up $200 to see that.

Ken Gross, a guest curator, is described on his Amazon page as the former “Executive Director of the Petersen Automotive Museum, in Los Angeles, California, for five years following a career in advertising and marketing. His car, travel, and motorcycle writing has appeared in Robb Report, The Rodder’s Journal, Automobile Magazine, and Road & Track.” No mention of concerns about the design of cars.

The article continues:

[Venable] rearranged the [IMA’s] organization chart so that all curators now report to Preston Bautista, who joined the staff in 2011. Bautista has a Ph.D. in art history but also studied advertising and knows statistics.

Ok, there’s nothing wrong with concern about the audience for art. It’s when audience considerations drive the art choices that things are out of whack.

The Star reveals Venable as a prodigious fundraiser and that’s good — the IMA, it says, overspent and drew down too much from its endowment during the tenure of former director Max Anderson.

I agree with Venable that the way back to balance is through programming. He should not cut back on programming; but it’s possible, even in a sports-crazy town like Indianapolis, to organize exhibitions that will be big draws. I’ve seen other museums do it; why not Indy?

Here’s another sad comment, though: The Star article — which should have had an impact on the city’s art lovers — was published on Feb. 21. Five days later, not a single comment was left beneath it, whether refuting, agreeing, showing concern, or applauding.

Is Indianapolis really that apathetic about its art museum?

Photo Credit: Matt Kryger, Courtesy of The StarÂ