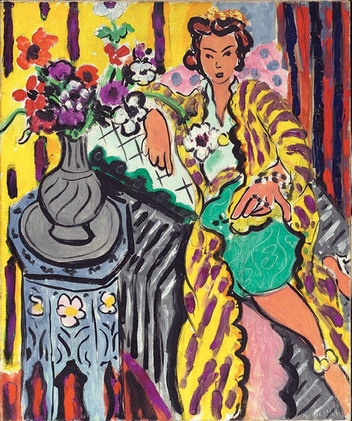

San Francisco beckoned me because of the Matisse/Diebenkorn exhibition at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Both artists are nothing if not seductive and, as I wrote in my review of the exhibition for The Wall Street Journal, published in yesterday’s print edition, “Rarely—if ever—in the history of modern art has a renowned artist been as deeply and openly inspired by another artist as Richard Diebenkorn was by Henri Matisse.”

So this was a natural, and like so many other naturals, surprising in that it had never been done in depth before. I loved it, as you will read, and I found different elements to admire in both venues: I saw it late last year at the Baltimore Museum of Art, where it was slightly smaller but just as great.

The curators, Katy Rothkopf in Baltimore and Janet Bishop in San Francisco, made different juxtapositions and were working with a different suite of galleries; each installation has its merits. For example, in Baltimore, the show seemed to build to a climax with Diebenkorn’s “Recollections of a Visit to Leningrad‖which visitors saw on its own large wall as they rounded a corner (though they likely stopped before getting to it to see other works on the way). The Baltimore wall label, as I recall, said “Recollections” was a summation of all Diebenkorn had learned from Matisse. Then they moved on to a large gallery that showed off all the Ocean Park series along with the Matisse paintings that helped inspire them. It practically glowed.

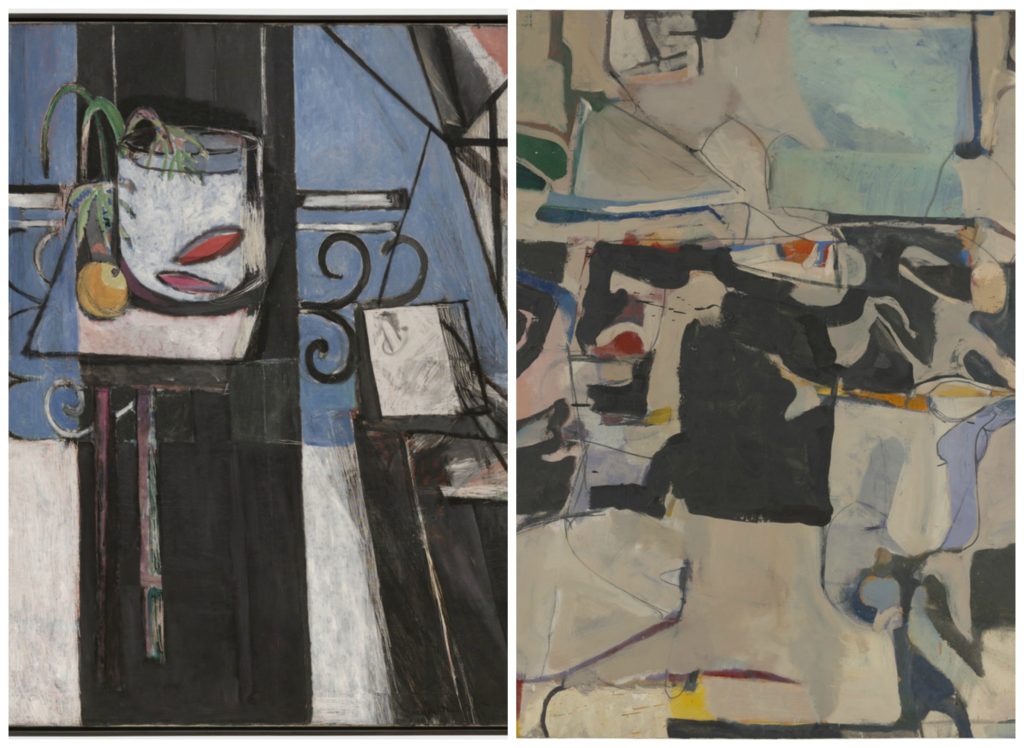

In San Francisco, Â the hang seemed more evenly paced. But, in a brilliant move, Bishop hung Matisse’s “Goldfish and Palette” nearer the start, alongside “Urbana #6.” The pairing stopped me in my tracks from the get-go. Have a look:

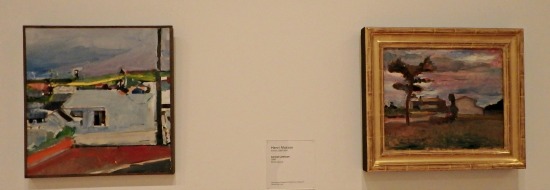

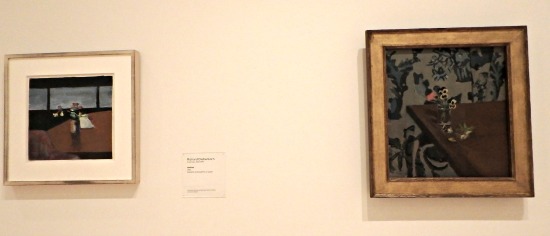

But in SF, I think, “Recollections” was less prominent, just one painting in a gallery of several, and the space there required the splitting of the Ocean Park series into two galleries. Still, Bishop made this revealing sequence (maybe Baltimore did too, I do not recall).

Both installations encouraged the close looking that affords real insight into both artists’ minds.

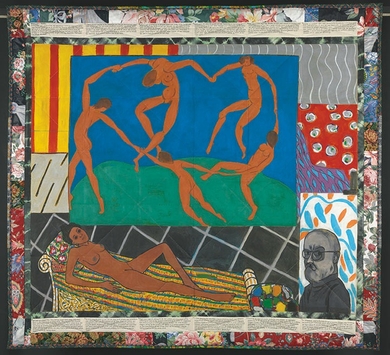

Diebenkorn seemed destined for a great career in art–at 26, he had already won a solo exhibition at the California Palace of the Legion of Honor. He was making abstract works then, and he continued to so do for years. But, as this show, which illustrates his evolution over the decades, he owes his greatness to his early exposure to Matisse. The works are accompanied by archival materials. Diebenkorn collected a vast library of publications about him, and he often later glued in color versions of the books’ black-and-white images. He would make notes, like the dimensions or the dates.

In fact, I came to the conclusion that a solo exhibition of Diebenkorn’s work would have been far less interesting than this dual show. (Not so for Matisse, obviously–he always looks great, to me.)

Here are a few more installation shots that I took at the SF exhibition–some, to my mind, more interesting than others.

UPDATE, 3/14: I just discovered this article written for SF MoMA that explains more about this exhibition and collaboration between Bishop and Rothkopf, which you can read here.

I don’t have too much to add to my review–if I had had more space, I would have explained some connections. For example, Roy Lichtenstein’s appropriation of a Matisse gold fish bowl in a bronze sculpture works because Lichtenstein used different means–open spaces in the bronze and vertical blocks of yellow and white color–to create the light reflections off the glass bowl that Matisse created in paint.

I don’t have too much to add to my review–if I had had more space, I would have explained some connections. For example, Roy Lichtenstein’s appropriation of a Matisse gold fish bowl in a bronze sculpture works because Lichtenstein used different means–open spaces in the bronze and vertical blocks of yellow and white color–to create the light reflections off the glass bowl that Matisse created in paint.