What makes your museum — the one you love, the one you promote, the one you work at, the one you most visit — different? Special?

Some museums are lucky enough to have a true, world-class masterpiece or two — the Frick’s Bellini, MoMA’s Starry Night, the Art Institute of Chicago’s Sunday on La Grande Jatte, etc. Better yet, some museums have specific, unduplicatable collections: If you are interested in Max Beckmann, you really must go to the St. Louis Art Museum, to name one example.

Back when I wrote a lot about corporations, and more particularly about corporate strategies, this differentiation was a big concern: what made Home Depot different from Lowe’s, or Cover Girl mascara different from Revlon’s? Marketing might do the trick — think Tide detergent’s sales over Cheer’s. But the companies that really did well were those that had more substantive product differentiation.

Back when I wrote a lot about corporations, and more particularly about corporate strategies, this differentiation was a big concern: what made Home Depot different from Lowe’s, or Cover Girl mascara different from Revlon’s? Marketing might do the trick — think Tide detergent’s sales over Cheer’s. But the companies that really did well were those that had more substantive product differentiation.

I thought of that the other day when I got a press release from the Denver Art Museum, announcing a $1.5 million 1 to 1 matching grant from the Mellon Foundation to support the creation of a $3 million endowment of a full-time, permanent textiles conservator, plus $250,000 to support a fellowship in textile conservation. I had already written about SPUN: Adventures in Textiles — the campus-wide docket of exhibitions related to textiles this summer, and I knew that SPUN was triggered by a $3 million gift to the DAM’s textile department.

So I asked the museum, how did the new grant come about? Did it ask the Mellon, was it taking the strategic course to put a lot of muscle into developing its textiles collection?

Indeed, the answer came back — this is not rocket science, but everyday good management — Christoph Heinrich, the museum’s director, and a development official visited Mellon in New York “to tell them about our Textile Art Department expansion and gauge interest in a proposal. They really liked the attention to textile arts, a medium they feel is underserved nationally, and invited us to apply for the grant,” spokeswoman Ashley Pritchard wrote back.

I also asked if I was reading the situation properly: DAM is known for Spanish Colonial art and Native American art, but other departments — which may have interesting pieces — are not considered to be exceptional (excepting British art, thanks to the Berger collection). Was it trying to add textiles to that short list? Again, from Pritchard:

We have a strong core collection of textiles in the textile art department, as well as the textiles held by other curatorial departments (Native Art, most notably). The curator is working to refine the collection – add to strengths, build out in certain areas, etc. We will become nationally known not only for our textile art collection and department but for our commitment to textile art conservation through this endowed position and the fellowship. A fellowship means that we are a center for conservation professional training, especially as it relates to textile art conservation, an underserved area.

This is smart. Especially in contemporary art, many museums have cookie-cutter collections. Textiles is a broad area that few museums focus on.

You can read more, in the museum’s press release on the Mellon grant. And here’s a link to some of the museum’s textiles in Spun – Adventures in Textiles_Image Highlights.

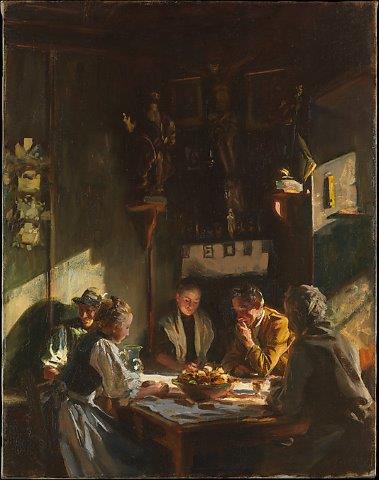

Photo Credit: Native American textiles at DAM, © Judith H. Dobrzynski