When Pluto splashed into our collective consciousness last month suddenly ready for its closeup, I learned a lot I hadn’t known. For instance, that although the orbits of Pluto and Neptune overlap, they are prevented from colliding by the stable 2-to-3 ratio in their rotations around the sun; Pluto goes around the sun in 247.94 earth years, and Neptune in 164.8, and 247.94/164.8 equals 1.50449…. This kind of mutually influenced periodicity, as it turns out (how was I an astrologer for thirty years without learning this?), is common among pairs, trios, quadruples of planets, moons, asteroids, and so on, and is called orbital resonance. Three of the moons of Jupiter exhibit rotational ratios of 1:2:4, and there’s even an asteroid that has a 5:8 dance going with respect to the earth. This is truly the harmony of the spheres, the surprisingly simple mathematical relations that planets in a rotational system fall into in response to each other’s gravity.

Chalk it up to my personal eccentricities that this suddenly gave me a whole new way to compose. I have an obsession with repeating cycles at different tempos, and it has sometimes been an aesthetic problem for me when the articulation points of those cycles coincide by chance. But the solar system, as it turned out, had been waiting with the solution all along. Inspired by this new knowledge, I realized I could use simpler ratios than I had been attempting (3:4, 5:6:7 instead of 17:19:23), but shift each one a slight amount so that the articulated beats would never coincide. It gave me a new way to create melody from the beats articulated among the different cycles. I immediately started a new piece, and five weeks later here it is, an extended pitch-and-rhythm study for three retuned Disklaviers:

Orbital Resonance (2015), 11:31

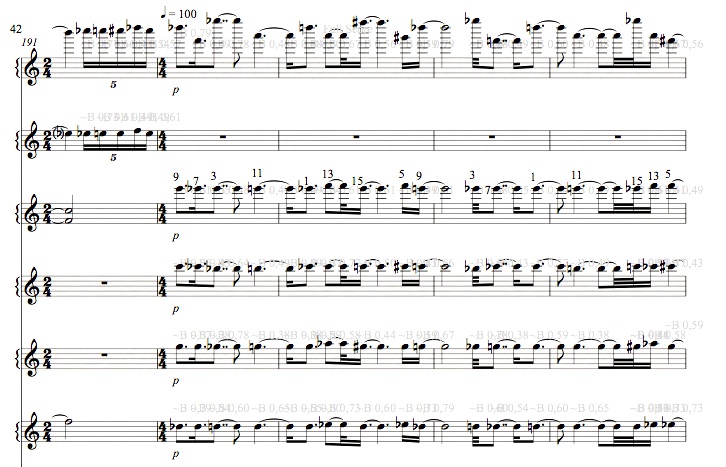

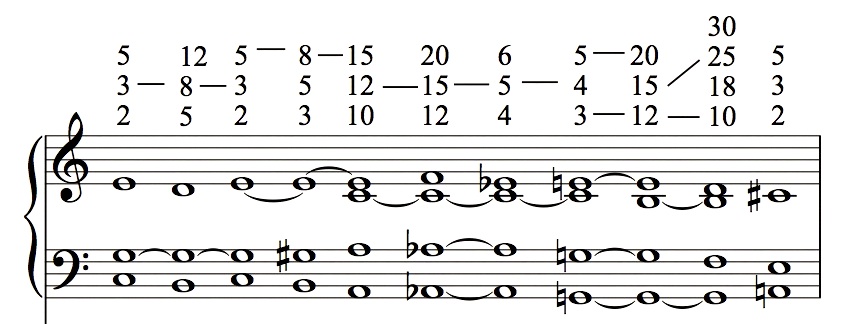

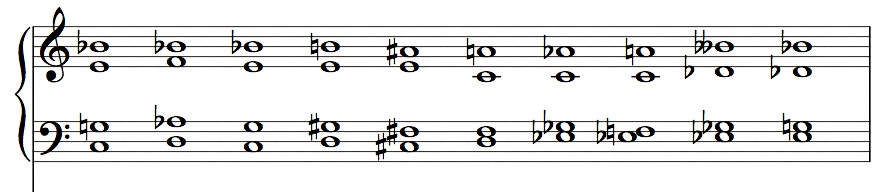

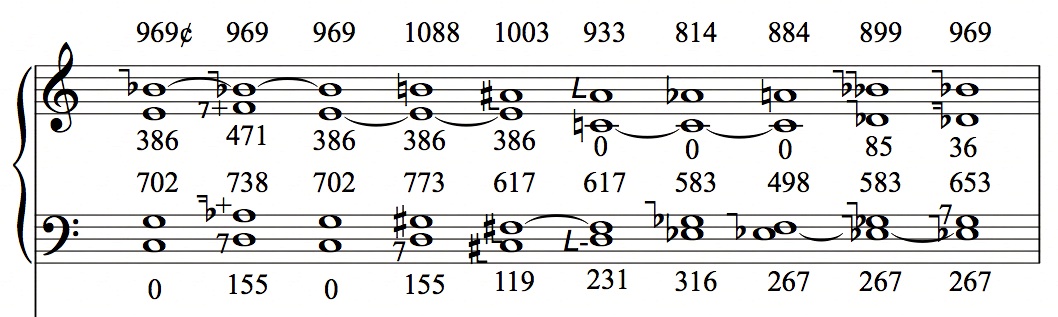

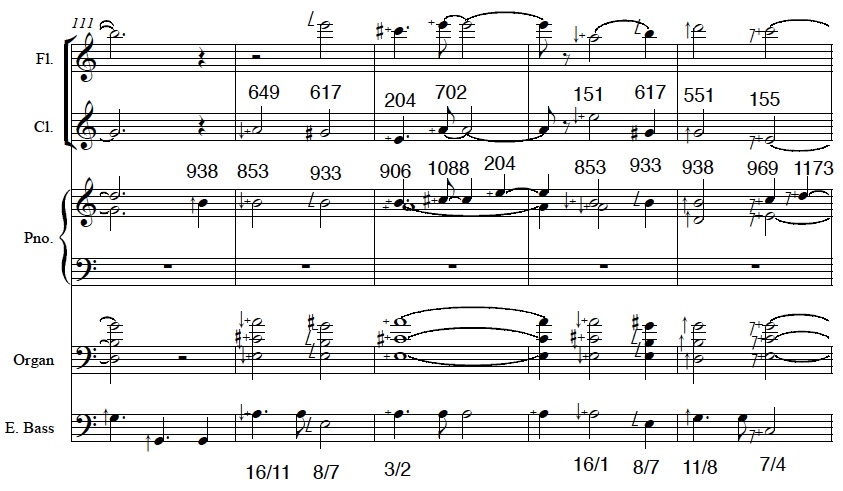

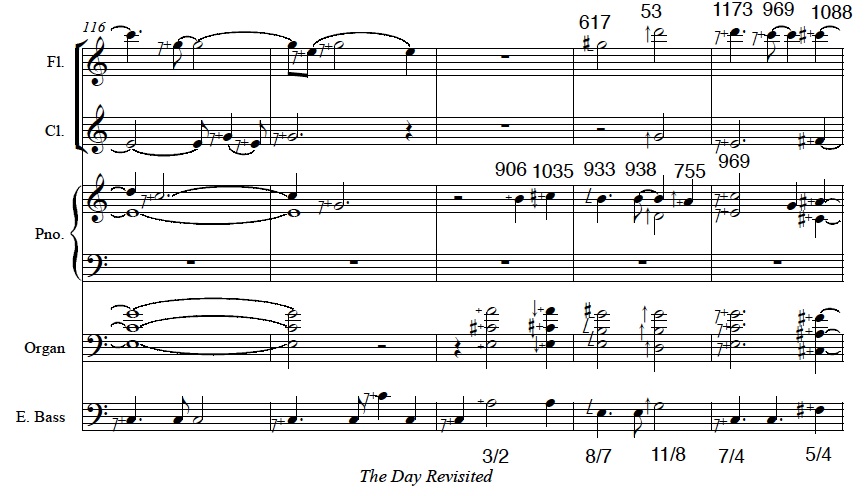

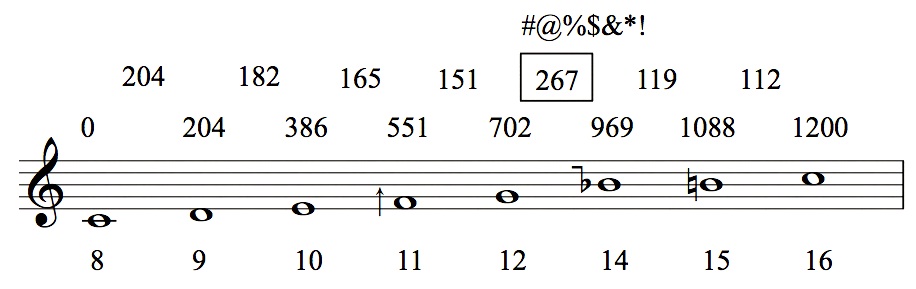

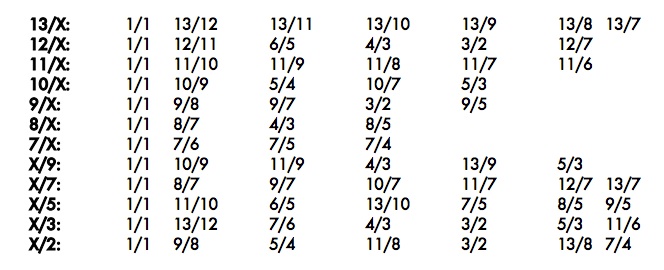

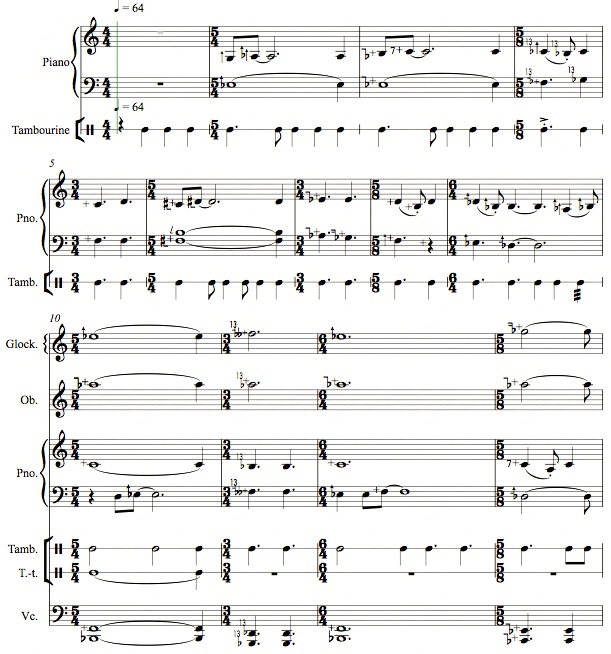

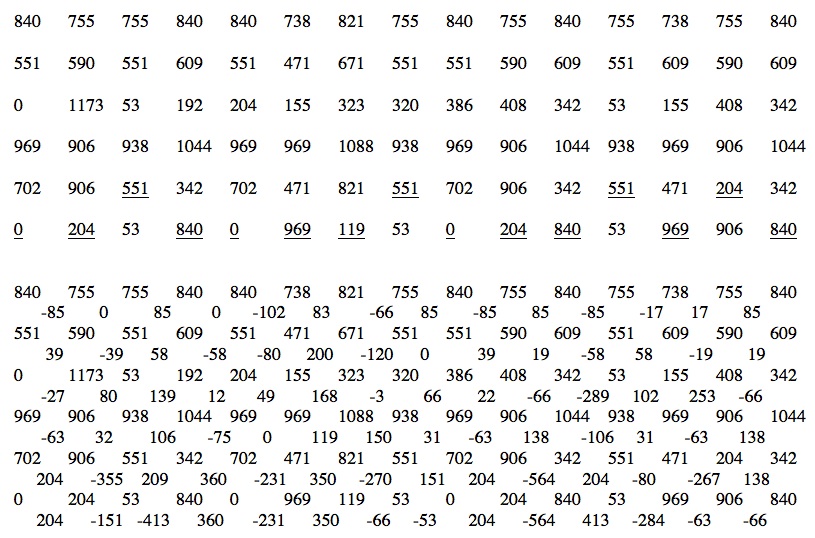

This is in what I call my 8×8 tuning, eight harmonic series built on the 1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th, 9th, 11th, 13th, and 15th harmonics of Eb, making 33 pitches in all. This is a complicated way to compose. First I had to write the piece for 17 pianos, one staff each, because I sometimes had 17 different pitch bends at once, and each pitch bend requires its own channel. After finishing the piece I had to figure out a workable retuning for three pianos to accommodate the 33 pitches. Next I had to map all those thousands of notes (sometimes in several different tempos achieved by tuplets) onto a three-piano score of six staves each. So I composed in something that looks like this (and if you can see all the little grayed-out numbers, those are the pitch bends on every note, along with harmonic series numbers so I could keep track):

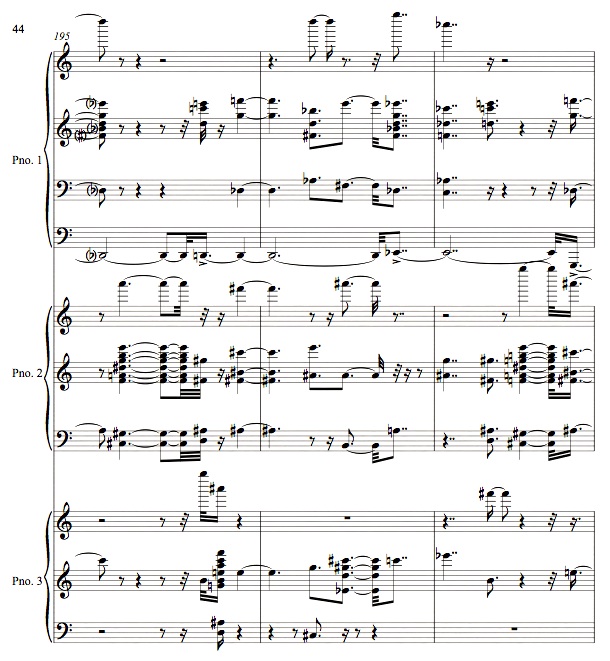

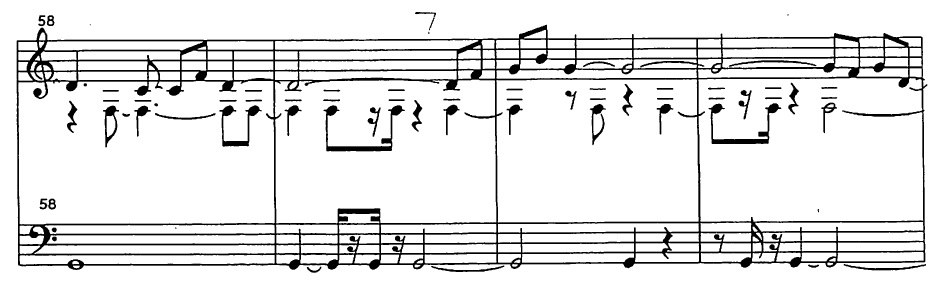

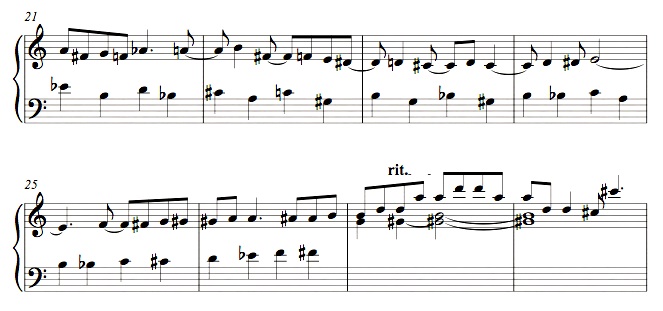

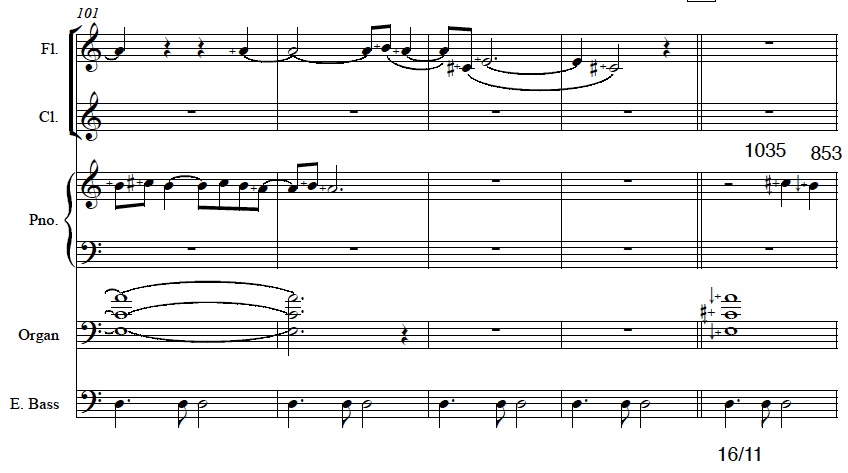

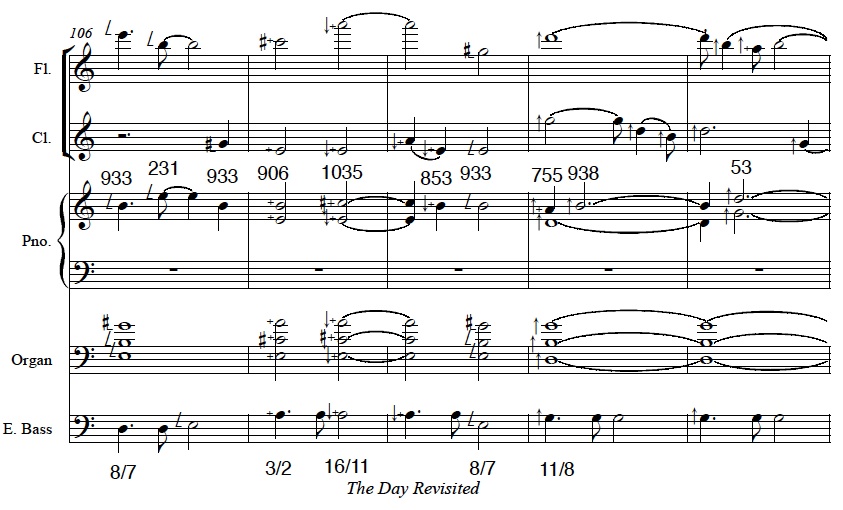

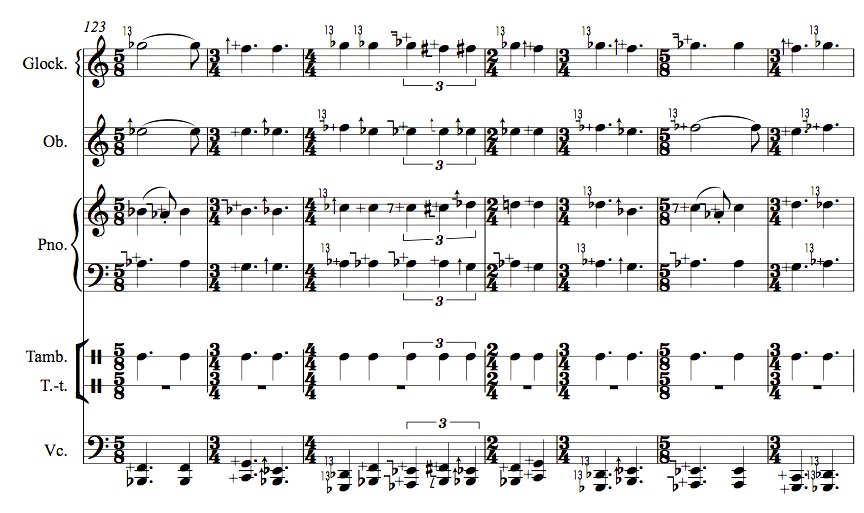

Then I transferred the notes to my three retuned pianos. The solution I came up with for distributing the pitches came out serendipitously. The harmonic series’ on 1 and 7 are mostly on piano 1, those of 11 on piano 2, and 13 on piano 3; the other harmonic series’ get divided up somewhat, but I use polytonal contrasts of 7, 11, and 13 a lot, so I tried to group those notes. It’s really not a piece for three pianos, but for one piano with 264 keys, but it could (after I’m dead and if someone ever wants to put the money into retuning three Disklavier grands) be played “live” on three pianos. And I like the fortuitous and wildly scattered way the sonorities bounce back and forth, like some whacked-out serialist extravaganza:

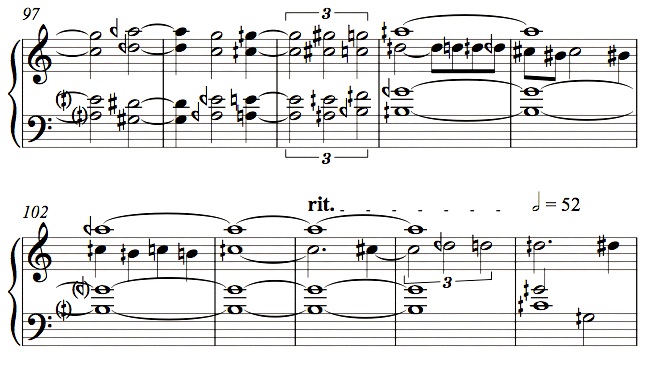

I think I can rest assured that no humans will ever attempt to play this. (If you look closely, you could find that, aside from the bass line articulating the 9-rhythm, there are always nine notes in every “simultaneity,”* and that the voice-leading is extremely chromatic; it’s pretty minimalist.) In order to get the kinds of rhythms suggested by the orbital resonance inspiration, I had to offset each cycle by a 32nd-, 64th-, or god help me 128th-note (I almost got used to double-dotted 16th notes) so that no points in the cycles would ever coincide. So it’s a sustained study in a quality of rhythm I’d never used before, and one which better allowed for melodic connections among the cycles. If you follow me. If you’re technically inclined I’ve got program notes that go further into the form, which is more logical than may appear on first hearing.

For years I’ve been trying to write something more elaborate both microtonally and polyrhythmically (and polytonally) than Custer and Sitting Bull (1999), and this is it: Nancarrow fused with Ben Johnston and La Monte Young with a dash of Piano Phase thrown in. (And by the way: this is not spectralist music, which approximates the harmonic series. This music actually employs the harmonic series, as Harry Partch, Ben, and La Monte were doing decades before the spectralists got started. The piece opens with the 65th and 66th harmonics of Eb and closes with the 54th, 55th, and 56th. Neither European 1/8th-tones nor Bostonian 72tet are sufficient for such distinctions.) I’ve got several other pieces for this setup started, and hopefully I’ll finish some of those as well. I’m hoping I might so well internalize the outlay of notes on the three pianos that I can skip the pitch-bend step and reduce the tedious part of the workload. There’s a PDF score on my score page if you’re technically intrigued. And as with Custer, I’ve dedicated the piece to Ben, who in 1984 started me down this incredibly labor-intensive road.

*I am a professor.