All right, it looks like, once again, the fate of postclassical music rests in my hands. So gather for the official announcement:

The 2014 John Cage Award ($50,000) from the Foundation for Contemporary Arts has been given to Phill Niblock.

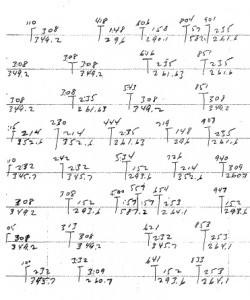

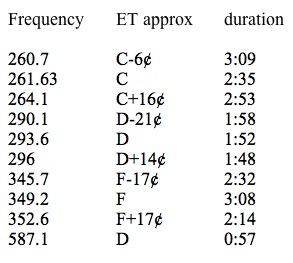

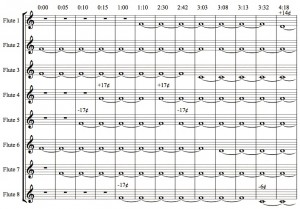

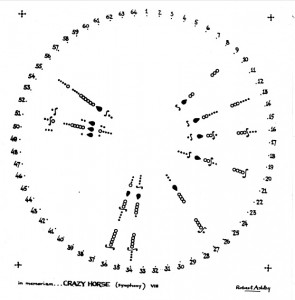

Phill Niblock (b. 1933) started as a conceptualist filmmaker and, untrained as a composer, began making musical scores for his films based on charts of pitch frequencies in cycles per second. In so doing he pioneered the use of small pitch complexes and very slow glissandos (pitch slides) often moving gradually between extreme consonance and extreme dissonance. For example, A Trombone Piece (1977) employs only the following frequencies, appearing in all combinations: 55, 57, 59, and 61 in one octave, 110, 113, 116, 119, and 121 in the next, and 220, 224, 228, and 232 in the highest octave. Rich in acoustic phenomena and almost imperceptibly slow metamorphoses, Niblock’s music sometimes involves the use of live performers moving around the audience and playing along with loudly amplified prerecorded drones. In recent years he has written, in similarly austere terms, for multiple orchestras, with great effect. Ever since his early recording Nothing to Look At, Just a Record, his titles have tended to be drily descriptive, but he has been a major influence on Downtown composers, such as Band of Susans, David First, Lois Vierk, and Glenn Branca, since the 1960s. Pieces available on commercial recording include Five More String Quartets, Held Tones, Hurdy Hurry (especially recommended), A Y U aka “As Yet Untitled,” Yam Almost May, A Third Trombone, Four Full Flutes, Disseminate Ostrava, and many others. (Read my 1999 Village Voice article on Niblock, “Master of the Slow Surprise.” No recordings are given here only because the acoustic phenomena in Niblock’s music aren’t captured adequately in the mp3 format.)

Phill Niblock (b. 1933) started as a conceptualist filmmaker and, untrained as a composer, began making musical scores for his films based on charts of pitch frequencies in cycles per second. In so doing he pioneered the use of small pitch complexes and very slow glissandos (pitch slides) often moving gradually between extreme consonance and extreme dissonance. For example, A Trombone Piece (1977) employs only the following frequencies, appearing in all combinations: 55, 57, 59, and 61 in one octave, 110, 113, 116, 119, and 121 in the next, and 220, 224, 228, and 232 in the highest octave. Rich in acoustic phenomena and almost imperceptibly slow metamorphoses, Niblock’s music sometimes involves the use of live performers moving around the audience and playing along with loudly amplified prerecorded drones. In recent years he has written, in similarly austere terms, for multiple orchestras, with great effect. Ever since his early recording Nothing to Look At, Just a Record, his titles have tended to be drily descriptive, but he has been a major influence on Downtown composers, such as Band of Susans, David First, Lois Vierk, and Glenn Branca, since the 1960s. Pieces available on commercial recording include Five More String Quartets, Held Tones, Hurdy Hurry (especially recommended), A Y U aka “As Yet Untitled,” Yam Almost May, A Third Trombone, Four Full Flutes, Disseminate Ostrava, and many others. (Read my 1999 Village Voice article on Niblock, “Master of the Slow Surprise.” No recordings are given here only because the acoustic phenomena in Niblock’s music aren’t captured adequately in the mp3 format.)

The 2014 Robert Rauschenberg Award ($30,000) from the Foundation for Contemporary Arts has been given to Elodie Lauten.

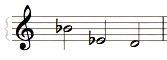

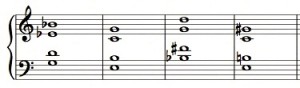

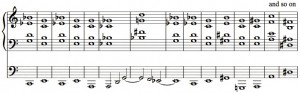

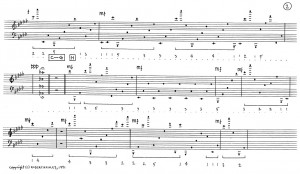

Elodie Lauten (b. 1950), the daughter of jazz drummer Errol Parker, came from her native Paris to New York in 1972 where she sang female lead for a band called Flaming Youth and fell in with the circle around poet Allen Ginsburg. She studied with La Monte Young and improvised many of her early keyboard works, composing within what she called “universal correspondence systems”, in which correlations were drawn among Indian Vedic cosmologies, hexagrams of the Chinese I Ching, astrological signs, scales, keys, and rhythmic patterns. Much of her music is cloudy, meditative, and static in its textures, though she also has a more neoclassic mode marked by melodic lyricism grounded in ostinatos; either way a haunting mysticism is rarely absent. Starting with The Death of Don Juan (1987), a ground-breaking work in which she would set a pattern for Downtown opera by performing vocally and on a harp-like instrument of her own invention over electronic backgrounds, she drifted toward opera and oratorio, and many of her recent works are quite large, including Waking in New York (based on poems chosen for her to set by Ginsburg); Orfreo (an opera based on the suicided conceptual artist Ray Johnson); and Deus ex Machina, a 100-minute cycle for Baroque-instrument ensemble and singers. (Read my 2001 Village Voice article on Lauten, “East Village Buddha.”) Listen to movement 1 of Lauten’s Variations on the Orange Cycle; “Jumping the Gun on the Sun” from Waking in New York; and “The Exotic World of Speed and Beauty” from Deus ex Machina.

Elodie Lauten (b. 1950), the daughter of jazz drummer Errol Parker, came from her native Paris to New York in 1972 where she sang female lead for a band called Flaming Youth and fell in with the circle around poet Allen Ginsburg. She studied with La Monte Young and improvised many of her early keyboard works, composing within what she called “universal correspondence systems”, in which correlations were drawn among Indian Vedic cosmologies, hexagrams of the Chinese I Ching, astrological signs, scales, keys, and rhythmic patterns. Much of her music is cloudy, meditative, and static in its textures, though she also has a more neoclassic mode marked by melodic lyricism grounded in ostinatos; either way a haunting mysticism is rarely absent. Starting with The Death of Don Juan (1987), a ground-breaking work in which she would set a pattern for Downtown opera by performing vocally and on a harp-like instrument of her own invention over electronic backgrounds, she drifted toward opera and oratorio, and many of her recent works are quite large, including Waking in New York (based on poems chosen for her to set by Ginsburg); Orfreo (an opera based on the suicided conceptual artist Ray Johnson); and Deus ex Machina, a 100-minute cycle for Baroque-instrument ensemble and singers. (Read my 2001 Village Voice article on Lauten, “East Village Buddha.”) Listen to movement 1 of Lauten’s Variations on the Orange Cycle; “Jumping the Gun on the Sun” from Waking in New York; and “The Exotic World of Speed and Beauty” from Deus ex Machina.

Pardon the lateness of this announcement, which became official two months ago and has gone almost unnoticed. Not since Meredith Monk’s 1995 MacArthur Award has any music award announcement made the world seem like such a benign place.