A keynote address I delivered in 2012 for the Nancarrow festival in London is going into Music Theory Online, the web journal of the Society for Music Theory. The above link [updated 3.25.14] was put up for my proof-reading convenience, and I don’t know how long it will remain before being whisked behind some paywall or something [it won’t be]. But it explicitly states that I own the copyright, so for now knock yourselves out. Readers of my Nancarrow book will not find anything particularly new here, though I do talk more, I think, about Nancarrow’s place in American music in general than I have elsewhere. But the prize is at the end: an mp3 of Nancarrow’s piano roll RR, one of his most elaborate finished works that isn’t one of the canonical (and I don’t mean canonic, I wish my students could grasp the difference) player piano studies.

Search Results for: nancarrow

Nancarrow, American

We’re having a pretty tedious reversion war over at Wikipedia vis-a-vis the Nancarrow article. I refer to Nancarrow as an American composer who moved to Mexico. I would be happy to call him an “American-born and -trained composer who took Mexican citizenship.” But a couple of guys, including Conlon’s late-life assistant Carlos Sandoval, insist that he must be referred to as a “Mexican composer.” I find this misleading, cognitively dissonant. Nancarrow did take Mexican citizenship in 1955, but he had few friends among Mexican composers, who were more oriented toward European than American music. I once asked him if his music had been in any way influenced by Mexican music or culture, and his characteristically laconic response was a flat “no.” Conlon spent his life working out ideas he had found in Cowell’s New Musical Resources, and he was championed and lionized by American composers (Carter, Cage, Garland, Amirkhanian, Reynolds, Mumma) long before the Europeans discovered him; his tiny influence on Mexican music has been mostly posthumous (one might cite the Microritmia duo).

This is a trivial fight, surely. But can you feel comfortable talking about “Alfred Hitchcock, American film director”? “Isang Yun, German composer”? “T.S. Eliot, British poet”? “Igor Stravinsky and Arnold Schoenberg, American composers”? Is an artist’s country of upbringing and training, the crucible in which his artistic vision was formed, to be so lightly cast aside because, for whatever political or personal reasons, he later in life had to live somewhere else?

Rouse Mastery, Nancarrow Mystery

Mikel Rouse’s music for Merce Cunningham’s dance eyeSpace, which I witnessed at the Joyce Theater in New York last night and is playing again tonight, was brilliantly post-Cagean. Cunningham and John Cage, as you know, made a decades-long joint career by making music and dance whose interaction was unplanned. Cage would make 20 minutes of music, Cunningham the same length dance, then just combine them, so that random coincidences could happen beyond the control of the creators. Mikel took the idea a step further – the dancers don’t even hear the music, because it’s on iPods. So the entire audience sat there listening with headphones to Mikel’s music, and because each iPod was on shuffle mode, each audience member was hearing different tracks and experiencing a different accompaniment to Merce’s dance.

And to make it even more interesting, Mikel and Merce’s sound designer Stephan Moore were playing tracks of environmental sounds into the hall – car horns, people talking, subway noise – at greatly varying volumes. Sometimes the environmental sounds would intrude into the iPod music, either because the noises got very loud or Mikel’s music very soft. So it was a partly communal experience, and more unpredictable than just listening to a series of Mikel’s gently ambient songs, because the noises and songs interacted randomly, and you weren’t always sure which sounds came from where. The whole concept realized Cage’s kind of unpredictable liveliness on a new level, one that allowed for Mikel’s pop-flavored beat. And one of the advantages to Mikel’s and my kind of multitempo music, as we semi-joked afterward, was that no matter what kind of rhythm the dancers were making, there was probably some background tempo being articulated by the music that went right along with it.

Mikel’s wife Lisa Boudreau (pictured) is one of Cunningham’s dancers, and this was the first time she’d ever had the chance to dance to Mikel’s music.  The dancers were forming and reforming in pairs, and wore elastic bands that they would tie each other together with intermittently. Forgive me for not describing more: dance is the most difficult art form for me to grasp, and I’ve never had any vocabulary for it. It looked like the picture.

The dancers were forming and reforming in pairs, and wore elastic bands that they would tie each other together with intermittently. Forgive me for not describing more: dance is the most difficult art form for me to grasp, and I’ve never had any vocabulary for it. It looked like the picture.

As if that weren’t enough excitement for one evening, the concert also featured the original choreography (as recalled by Carolyn Brown and others) of Merce’s dance, titled Crises, for Conlon Nancarrow’s first seven Player Piano Studies, done back in 1960. The Cunningham Dance Group kept that in their repertoire until 1964, and there’s apparently a primitive video that they were able to use in the reconstruction. (This Cunningham Dance tour eventually led to the short-lived 1969 Columbia recording of the early Studies.) The dance was kind of robotic and hiply modernist, in skin-tight yellow, red, and salmon tights. In Cage-Cunningham fashion, switches from one Study to the next were not synchronized with sections in the dance. I was paying especially close attention because next May in Boston, Mark Morris is choreographing some of my Disklavier Studies, and I was curious for something to comare with.

The strange thing, that several of us had a big powwow about afterwards, was that one of Conlon’s Player Piano Studies was one no one recognized. Trimpin had supplied MIDI files of the early studies so they could dance to a Disklavier (Cunningham always uses “live” music), but they found that the current MIDI files (which I also have) didn’t match the early tape. So they had to use the old tape, in the middle of which was there was a three- or four-minute Nancarrow study that I’d never heard before. Its melodic quirks sounded exactly like Nancarrow’s style, except that the tune was a little more repetitive and sing-songy, more influenced, perhaps, by the jazz that Conlon had played on trumpet in his jazz gigs of the 1930s. Various theories were advanced, including the possibility that David Tudor had improvised something, but given Conlon’s tendency to become dissatisfied with works and disown them, I strongly suspect that this was an early study that he threw away, probably because the jazz influence was too undigested. I’m going to get a recording and see if I can analyze the tempo relationships. Had they asked me a couple of months ago, I’m sure I could have supplied them with a MIDI version.

The Nancarrow of Fargo

I went to Fargo to visit Henry Gwiazda. He used to make sampling pieces in virtual audio, placing sounds in three-dimensional space. He despaired of that, because it only worked with the listener in a certain relation to the loudspeakers, which meant that he could only play his music for one person at a time. (Though the effect, captured in his piece Buzzingreynoldsdreamland, is pretty astonishing. You can experience the piece on an Innova CD, but you have to set up your stereo speakers just right.) He’s more recently gotten involved in a video-animation/sound art fusion instead. He’s got some new pieces coming out on an Innova DVD that’s going to be beautiful. (My interview with him will be an extra feature on the DVD, and that’s what we were doing.) I think of Henry as the Nancarrow of my generation, because he’s reclusive, few people know his work, he’s working with technologies no one else is using, and yet he also has a kind of low-tech element to his work, since his sound samples and video models all come from commercial sound libraries and modeling software. He picks up old technology no one had thought of using creatively and makes evocative poetry with it, the way Nancarrow did with the player piano. Of course you’ve never heard of him: he’s 53, and Nancarrow was discovered at 65.

I’ve put up one of Gwiazda’s virtual audio works, thefLuteintheworLdthefLuteistheworLd, for you to listen to, but you HAVE to use headphones, with left and right channels in the appropriate ear, to get the piece’s amazing three-dimensional spatial effects.

Henry and I have argued for years about the meaning of modernism. At present, he defines modernism as the assertion that the world is more complex than we can understand; he defines postmodernism as the assertion that the world is more complex than we can understand, and that’s fine, we don’t need to understand it. He’s recently distanced himself from both positions, and feels that we both can understand the world, and urgently need to do so. (I consider this postminimalism, but we haven’t come to agreement on that yet.) Consequently, he’s making animated videos that capture extremely mundane moments in the protagonists’ lives, and drawing attention to small, sensuous details as a way of attuning the viewer to details in his own surroundings. It’s lovely, resonant work, that does make you see the world a little differently afterward.

But Henry’s given up on the new music scene, on the grounds that most composers consider themselves musicians but not artists, and cultivate imitative, recreative thinking rather than creativity. He showed me an article in this week’s Scientific American Mind (Henry is one of the most science-conscious composers I know), which defines creativity as divergent thinking, imaginative leaps into the unknown, but notes that almost all education emphasizes only convergent thinking, which consists of learning well-trodden paths and honing in on singular correct answers. Most of the way we teach composition, Henry feels, is scientifically mistaken, because we teach by examples and models already used by others instead of encouraging off-the-wall thinking and problem solving. Hindemith, he thinks, did tremendous damage to American music by encouraging composers to think of music as a matter of craftsmanship. Henry is himself one of the most off-the-wall, imaginative artists I know, someone whose mind is well accustomed to jumping off at bizarre angles. In the other arts that’s valued; in music, it always seems a little suspect.

Also, like Feldman, Henry has a refreshing way of seeing through the blinkered assumptions of the composing world. A story he told me suggests partly where he got it, from one of his composition teachers at Cincinnati College-Conservatory (where Nancarrow was also educated): one Scott Houston, since departed. On Henry’s oral doctoral exam, Houston asked the question, “Say you’re writing a piece for woodwind quintet. What considerations do you think about when you start out?” Henry muttered something about the relative ranges of the instruments. “Wrong.” He tried eight or nine other platitudes, all greeted with, “Wrong… wrong… wrong.” Finally, in some exasperation, Henry blurted out, “Well to tell you the truth, I’d never write a woodwind quintet, because it’s an ugly combination of instruments.” “DAMN RIGHT!,” shouted Houston, slamming his first on the table. That was the answer he was looking for.

Convergent thinking, true, but what a refreshing example.

The Nancarrow Saga Continues

Conlon Nancarrow, like all artists interesting to read about, was a fount of idiosyncracies. One was the tendency to bring out earlier music, often abandoned works from his early years, as brand new music. His most spectacular instance of this was renumbering his Player Piano Studies Nos. 38 and 39 as Nos. 41 and 48 because he was using them to fulfill commissions, and didn’t want his patrons to know that they were paying for works that had already been completed prior to the commission. (No shame in this, by the way; Stravinsky did it as a matter of course, and recommended the practice.) As a result, in the complicated numbering of Nancarrow’s 50-odd studies, Nos. 38 and 39 do not exist.

Now this personal quirk is occasioning some interesting wrinkles in Nancarrow scholarship, and I’ve spent the week unraveling some of the mysteries I wrote about last week. First of all, the Three Movements for Chamber Orchestra, his last work, since it’s receiving it’s US premiere with Alan Pierson and the Alarm Will Sound ensemble this Saturday, Feburary 19, at Columbia University’s Miller Theater. Around 1993 Conlon received a commission from New York’s Parnassus ensemble. Having already suffered a stroke, and not feeling up to conceiving a major work from scratch, he was rumored to have gone through some of his abandoned player piano works (of which there are dozens) and orchestrated them. Now, thanks to files Alarm Will Sound has sent me, I’ve been able to confirm this.

Trimpin labeled all the unknown piano rolls alphabetically, A through Z, then AA through ZZ, up through BBB. Some of these are mere sketches or jokes, some apparently early versions of studies you’re familiar with, others entirely completed works he abandoned for some reason, and one of them remarkably Romantic in tonality, kind of Lisztian. The Three Movements for Chamber Orchestra is based on three separate rolls, marked R, AA 39 A (because either Trimpin or I once thought this had something to do with #39/48), and “UK Finished A,” so labeled by Trimpin – “UK” meaning unknown, and “Finished” to indicate that it was clearly a completed work. (If memory serves, this last roll is one of the ones Trimpin presented at the Kitchen in 1993.)

R is only a rhythmic canon using five pitches, and might have been presumed to have been written for Conlon’s abortive experiments with a percussion machine in the 1950s; however, I’m not so sure of that, because the five pitches are spaced out at octaves, and the percussion rolls seem to used a chromatic scale over a much smaller range. Alan Pierson confirms that the first movement is only for percussion, and that the tempo relationships (which I couldn’t quite figure out from the piano roll) are 75:96:105:120:126. This doesn’t quite correspond to the roll, which seems to be 75:84:96:105:120; some change must have been made while arranging. Also, this is a remarkably complex ratio for Conlon, the kind of number series he used in his last few works, but never in his early music. I wonder if that suggests a more recent time period.

The second movement seems pretty literally based on AA 39A. The third starts off based on UK Finished A, but some notes are missing and altered, and I’m still curious as to how this differs from the original. UK Finished A contains a large canon, but one somewhat obscured by an additive process in which chromatic pitch gestures repeated over and over with one more pitch added each time. I’ve put up a MIDI version of UK Finished A here, if you’d like to listen and compare it with the third of the Three Movements being premiered this weekend.

As for the named earlier works for player piano cited by Helena Bugallo in her dissertation, she’s kindly clarified their provenance for me. The Didactic Studies are all different versions of Study #2a, simply the same tune and ostinatos but with a variety of different tempo relationships. I had found these scores and piano rolls in Nancarrow’s studio, and wrote about them, and they are almost certainly a product of the 1950s when he was first starting out. But apparently in a 1980 interview he referred to them by the title Didactic Studies and avowed an intention of publishing them as a set. Perhaps he really did return to this piece as late as 1980, but it seems odd. I think he had abandoned any such intention by 1988, because I looked at those scores then with his supervision, and he said no such thing. The other work, For Ligeti, was apparently presented publicly in 1988 (though he also never mentioned this to me either). This, according to Sacher Foundation archivist Felix Meyer, has been found to be an early study originally intended as Study #3, but withdrawn. I’m eager to get more information.

In addition, two readers wrote to inform me that, while several of the recordings of the Canons for Ursula contain only two canons, there are two recordings that include the third, or rather middle, canon. One was a 1996 recording by Joanna MacGregor which may soon be rereleased on her own label. The other is the brand-new Wergo recording by Helena Bugallo herself, on which, in addition to some player piano study transcriptions that she plays with her duo partner Amy Williams, she also plays all three canons. Sorry I missed this fact.

There are doubtless new Nancarrow works yet to come to light; a few years ago at a Nancarrow conference in Mexico City someone showed me a couple of brief 1940s piano pieces found among his papers, and I myself had discovered a movement for large orchestra apparently intended for an expanded version of his Piece No. 1 for Small Orchestra from about 1942. But I suspect most of what we have to look forward to comes from the piano rolls, and perhaps I’ll have time to get some of my MIDI files of them into performance shape. If so, I’ll post them to Postclassic Radio.

Conlon Nancarrow, Posthumously

In my book on Conlon Nancarrow I analyzed 65 of his works, which was everything known to me at the time. However, like Schubert, Conlon goes on producing music posthumously, and recently I’ve been getting information on three pieces I didn’t include. First, pianist Helena Bugallo, who has been performing his player piano works in piano duo arrangements, has just completed her doctoral dissertation at SUNY Buffalo, entitled Selected Studies for Player Piano by Conlon Nancarrow: Sources, Working Methods, and Compositional Studies. (It’s available from the ever-helpful UMI Dissertation Services.) She lists two works I’d never heard of, called Didactic Studies and For Ligeti, with dates 1980 and 1988 respectively, but neglects to mention what medium they’re written for. [2/14 UPDATE: They’re for player piano. I’ll be writing more extensively to give all the details soon.] These may have come from about 60 unnamed (and unnumbered) player piano rolls that Conlon had left in his studio as unfinished or abandoned works or sketches. Bugallo did her research in the Nancarrow archive at the Paul Sacher Foundation in Basel, whence all of Nancarrow’s materials were moved before he died. I knew that a group of odd little piano pieces (for live player) had been found, but they were written clearly in Conlon’s 1940s style, and can’t have been the Didactic Studies referred to if the latter truly came from 1980.

Something else Bugallo provides is a renotated complete score, recreated from the player piano roll, of Conlon’s Study #47, the final score of which had been lost. Very welcome.

More excitingly at the moment, the chamber orchestra Alarm Will Sound is giving the US premiere next Saturday, Feb. 19, at Miller Theater in New York, of Nancarrow’s Three Movements for Chamber Orchestra, supposedly his last work, written in in 1993. I had heard from Conlon’s assistant Carlos Sandoval that this was an arrangement of music from some much earlier player piano rolls. Nancarrow had a stroke (actually a stroke-like condition brought on by pneumonia) in January of 1990, and afterward his music became much simpler, almost naive, in a not unattractive way. He was commissioned by Parnassus for an ensemble piece, and – so the story I heard goes – had Carlos help him arrange something from an unnumbered player piano study, since he didn’t feel up to conceiving a major new work. (Some of the abandoned player piano rolls are complete multi-movement works, so this is plausible.) But I had also heard the work was a quintet, and virtually unplayable, and it turns out to be for three winds, three brass, five strings, percussion, and piano. So this is a mystery, and I’m eager to get it cleared up.

One further Nancarrow mystery, which I’ve never addressed in public: You’ll occasionally read references to Nancarrow’s “Three Canons for Ursula,†which he wrote for Ursula Oppens, but on the available recordings there are only “Two Canons for Ursula.†The third canon required the pianist to play four tempos at once. Conlon showed me its opening pages, but told me he had abandoned the piece as too difficult to play. So Ursula premiered the Two Canons, and in recent years the third canon has surfaced, and has apparently been played by a pianist in Europe. English composer Thomas Ades, in a review of my book, lambasted me for “hiding†the existence of this third canon, but Conlon had told me he was deleting it from his catalogue; I believe he hadn’t even finished it at the time, and didn’t plan to. Since I published my book while he was still alive, I felt that I should limit my assertions about his music to ones that he didn’t contradict. Now that he’s gone and the archive at Basel is being organized and mined by scholars, however, new Nancarrow music is coming to light, and it’s certainly true that he wrote a lot more pieces than he officially acknowledged.

Did Nancarrow Have Days Like This?

I’ve had a couple of opportunities to play my Disklavier pieces lately, in New York and at Bard. A Disklavier, just to be very clear since so many get the wrong idea, is an acoustic piano, with real strings struck by felt hammers and vibrating in the air, but operated from a computer (or disc) via MIDI instructions. The keys move, just as though a pianist were playing them. It’s a modern player piano, only the paper piano roll is now replaced by a sequence of digital information.

Anyway, the response I get is kind of deadeningly repetitive. The pieces I usually play are jazzy, impressively fast, and sort of humorous, and generally make a good impression. But afterward, I’m invariably approached by two or three or four people who ask, “Gee, isn’t there some way to make it possible for live pianists to play those pieces?†They ask as though they suspect it’s a possibility I’ve never considered, as if they expect me to strike my forehead and shout, “Of course – a live pianist! Why didn’t I think of it?”

Now, number one: I get a big kick out of watching the Disklavier. It’s fun to watch all those keys ripple up and down the keyboard; I take the front cover off, when it’s an upright, and you can watch the hammers fly by as well. In Australia I also hooked up my computer to a projector, so the audience could watch the Digital Performer file scroll by, which looks exactly like a player piano roll, only with the notes running horizontally instead of vertically. I got the idea from watching Conlon Nancarrow’s player pianos, which were incredibly more fun to watch live than to listen to a recording of. You’d see a diagonal line of holes appear on the piano roll, and know that a huge glissando was coming, and it would blast in a split second later – it was like being on a sonic roller coaster, because you could see what you were headed for just a second before it happened. I love watching player pianos as much as I’ve ever loved watching a live pianist.

Number two: I’ve written a lot of piano music and a lot of Disklavier music, and I approach them with different mindsets, just as though they were different instruments. When writing for Disklavier I don’t even think about spacing the notes so that a human hand can reach them. If I want to write a melody in lightning-fast quintuple octaves, or a whole string of six parallel sixths, I go right ahead. And the whole point is to be freed from downbeats and meters, so the first thing I’ll do is lay out a whole set of nested tempo relationships, like 7-against-9-against-11-against-13-against-17, and then fill in the notes, knowing that notes in one line will coincide with notes in another line only at downbeats, and then I try to avoid putting notes on downbeats. By doing that I get exactly what I want, which I feel is a wonderful spontaneity of notes bubbling up, not randomly, but like corks bobbing up and down on brisk waves, with patterns that are repetitive but wholly unsynchronized.

I know that there are pianists, like Ursula Oppens, who have trained themselves to play some pretty complex rhythms; in fact, the Helena Bugallo-Amy Williams Piano Duo played some of Conlon Nancarrow’s early Player Piano Studies in New York this past Thursday, and I couldn’t be there because I was impersonating Abraham Lincoln that night. (Scroll down if you really have to know why.) But it’s one thing to play a 22-tuplet over a 4/4 beat in a Chopin nocturne, it’s something else to play steady lines of 13-against-29-against-31 for several measures at a time. I imagine it can be done. What I don’t imagine is that it would sound the way I want it to sound, with the same spontaneity and bubbly effect. I did, by request, transform one of my Disklavier pieces (Folk Dance for Henry Cowell) into a live-pianist piece (Private Dance No. 2), and I’ve never been totally convinced by the result. In addition, pianists fudge rhythms like these, and I frequently change harmony in mid-measure among several lines at once, the notes all changing chord suddenly like a flock of birds mysteriously reversing course with one mind. I don’t see how a pair or trio of pianists would be able to “sort of†play all these tempos at once, and also be able to so closely synchronize that when one switches to the E minor triad on the fifth note of a 17-tuplet, the other switches to that chord on the corresponding fourth note of a 13-tuplet.

Maybe it could be done. If someone can figure out how to do it, I’ll applaud. But the other thing I can’t understand is, why would anyone want to go to that much trouble? Why are so many people so dissatisfied watching the Disklavier, even people who visibly enjoy it? Sometimes the question comes from a pianist who is dazzled by the music and wants to play it, and that’s flattering. I wish I could interest these pianists in the eight or so piano pieces I’ve written for human players, but I rarely do. One person said that the Disklavier doesn’t give the feel that a live pianist can. Well, that’s a point, I guess; but unlike the old player pianos, I can adjust the dynamic (hammer velocity) separately for every note, and I do a tremendous amount of fine-tuning to accent just the right note in a phrase, humanize the attack points, create the effect of a live pianist hesitating on a high note or beginning a trill slowly. I simulate live performance with what strikes me as a high degree of realism, and I am strongly tempted to assume that psychology plays a role in perception here – the music often sounds nuanced, tentative, slightly irregular just the way a pianist would play it, but since there is no pianist, the listener fools himself into believing that it sounds regular and mechanical.

Or is it just that people don’t enjoy watching machines play music? I’ve seen an entire orchestra of MIDI-operated machines play music in Trimpin’s studio in Seattle, and it was one of the great musical thrills of my life. Computer-operated acoustic instruments are coming, folks – they’re part of your future. Get used to ‘em or ignore ‘em, but you can’t stop ‘em.

I know Conlon used to be bothered by similar queries. In his day, there was always the complaint (he got it from Aaron Copland, among others) that a player piano performance was the same every time, that there was no interpretive deviation from one playing to the next. Conlon’s usual response was, a Picasso painting is the same every time you see it; a Shakespeare sonnet is the same every time you read it; why is only music required to be different every time or you can’t enjoy it? Today’s audiences, however, are so inured to recordings and even near-identical performances that that objection seems to have disappeared. But for some reason people are just bothered by using a computer to do something that humans have always done, and they seem willing – as I am not – to put up with any compromise to transfer that activity back into the traditional realm of the performer-audience relationship. I wish I understood why. Because, sadly, I think people who strongly feel that way are just going to have to listen to someone else’s music, and there’s a lot out there.

A Critical Conspiracy

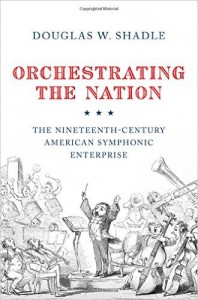

Two books I’ve read recently had a notable impact on me. One was Orchestrating the Nation: The Nineteenth-Century American Symphonic Enterprise (Oxford) by Douglas Shadle, who’s at Vanderbilt. It’s a history of the relationships among 19th-century American composers, critics and conductors, and particularly of the Europhile bias American composers had to face at every step. Music critics were enamored of what came to be called The Beethoven Problem: a composer of symphonies had to both imitate and expand on the Master’s principles. They developed a set of binary goalposts that could be relocated to frustrate any American contender: If your music was too similar to Beethoven’s, it was derivative; if not similar enough, it failed to build on eternal principles. If it followed the Mendelssohn-Schumann line it was timid; if it veered toward Liszt and Wagner, it was damned for being mere program music. If it used American source material, it lacked “symphonic dignity”; if not, it represented inauthentic European wannabe-ism. If audiences loved it though the critics didn’t, then it merely appealed to the superficial; and even if critics liked it and audiences didn’t, then it may be intellectual but will never appeal to the common man. Meanwhile, Europeans as minor as Jan Kalliwoda were enthusiastically welcomed into the repertoire. As Shadle puts it, “critics relegated the music of nineteenth-century American composers to the dustbin of history while applying mutable standards of criticism to each new crop [p. 263]”. And so each new American symphonist – Anthony Philip Heinrich, William Henry Fry, George Frederick Bristow – would create a frisson of public excitement only to be forgotten and dismissed in short order, creating a mistaken impression that no history of American symphonic music existed.

Two books I’ve read recently had a notable impact on me. One was Orchestrating the Nation: The Nineteenth-Century American Symphonic Enterprise (Oxford) by Douglas Shadle, who’s at Vanderbilt. It’s a history of the relationships among 19th-century American composers, critics and conductors, and particularly of the Europhile bias American composers had to face at every step. Music critics were enamored of what came to be called The Beethoven Problem: a composer of symphonies had to both imitate and expand on the Master’s principles. They developed a set of binary goalposts that could be relocated to frustrate any American contender: If your music was too similar to Beethoven’s, it was derivative; if not similar enough, it failed to build on eternal principles. If it followed the Mendelssohn-Schumann line it was timid; if it veered toward Liszt and Wagner, it was damned for being mere program music. If it used American source material, it lacked “symphonic dignity”; if not, it represented inauthentic European wannabe-ism. If audiences loved it though the critics didn’t, then it merely appealed to the superficial; and even if critics liked it and audiences didn’t, then it may be intellectual but will never appeal to the common man. Meanwhile, Europeans as minor as Jan Kalliwoda were enthusiastically welcomed into the repertoire. As Shadle puts it, “critics relegated the music of nineteenth-century American composers to the dustbin of history while applying mutable standards of criticism to each new crop [p. 263]”. And so each new American symphonist – Anthony Philip Heinrich, William Henry Fry, George Frederick Bristow – would create a frisson of public excitement only to be forgotten and dismissed in short order, creating a mistaken impression that no history of American symphonic music existed.

Critics had more power back then than they do now, but Shadle makes clear that star conductors like Theodore Thomas nurtured similar sets of shifting criteria to save themselves the trouble of performing American works. The book’s arch-villain, though, is famous Boston music John Sullivan Dwight. For decades I’ve tried to find something to admire about the guy because of his connection to the Transcendentalists, but he was the worst of the worst of those who thought the Europeans had said it all and so Americans shouldn’t bother trying, and Shadle hangs him with his own hypocritical words again and again. (I’d like to think his type of critic died out with the late Andrew Porter.)

Meanwhile, Shadle also elucidates the aesthetic strategies of the American Romanticists in a way that made me hear them differently. I had always found Fry’s Santa Claus: A Christmas Symphony rather silly, but Shadle discusses it in terms of Italian operatic stereotypes and Fry’s deliberate rebellion against German paradigms, and I now hear it as narrative and somewhat moving. I also developed some admiration, if not affection, for John Knowles Paine’s Second Symphony, as an attempt to master the Liszt/Wagner vocabulary without giving in to programmatic tendencies. The book introduced me to George Templeton Strong’s programmatic Second Symphony Sintram, which is quite impressive and better than the other music I’d heard of his – another work widely lauded and then quickly forgotten. And in the 1880s the next great American composer was supposed to be Brooklynite Ellsworth Phelps (1827-1913), who is almost entirely forgotten today, and the score to his Emancipation Symphony tragically lost. Shadle and I both consider Bristow overdue some major attention, and he includes some excitingly long musical examples from his 1893 Niagara Symphony, about which I’d never been able to find any information.

More than anything else, Orchestrating the Nation illuminates the origins and myriad strategies of the classical music world’s eternal animus against American composers. As I teach every week among student composers who can’t be bothered with Ashley or Nancarrow but sing the praises of Kurtag and Lachenmann, Saariaho and Haas, I feel like little has changed. If it takes a hundred points to achieve parity with Beethoven, you get fifty free points just for being born in Europe. Shadle shows how long that’s been going on.

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

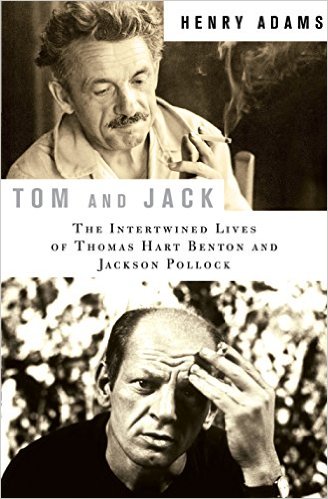

The other book is by art scholar Henry Adams, Tom and Jack: The Intertwined Lives of Thomas Hart Benton and Jackson Pollock (Bloomsbury Press). Benton and Pollock have long been two of my favorite painters – my adolescent worship of Pollock has toned down a little over the years, but my fascination with Benton only increases. But the art world, as it turns out, hates Benton for reasons parallel to the condescension of composers toward Sibelius and Rachmaninoff, for his too-late-representational, cheesy-narrative Americana-ness. And so, every account of Pollock’s life soft-pedals his indebtedness to Benton, who was his teacher and lifelong confidant. In the official narrative, Benton was only useful to Pollock as someone to rebel against.

The other book is by art scholar Henry Adams, Tom and Jack: The Intertwined Lives of Thomas Hart Benton and Jackson Pollock (Bloomsbury Press). Benton and Pollock have long been two of my favorite painters – my adolescent worship of Pollock has toned down a little over the years, but my fascination with Benton only increases. But the art world, as it turns out, hates Benton for reasons parallel to the condescension of composers toward Sibelius and Rachmaninoff, for his too-late-representational, cheesy-narrative Americana-ness. And so, every account of Pollock’s life soft-pedals his indebtedness to Benton, who was his teacher and lifelong confidant. In the official narrative, Benton was only useful to Pollock as someone to rebel against.

But Adams – whose ability to elucidate art in words is absolutely thrilling – shows at incontrovertible depth that Pollock used Benton’s methods for energizing a painting throughout his career, and especially at the end; that it was Benton who taught Pollock how to organize a painting, and the difference between Benton’s narrative painting and Pollock’s abstractions does not obscure the means they both used to focus energy within a flat canvas. Adams also takes issue with the whole Clement Greenberg ideology about how what was important about Pollock’s and all the abstractionist painting was the acceptance of flatness, which he finds completely wrong-headed given the evocations of three-dimensional depth in Pollock’s paintings. The book surprised me with how much I could learn about art, even art I was already familiar with, by reading about it. And I loved this musing, at the end, by Benton about what he considered lacking in abstract art:

If you notice: the careers of abstract artists so often end in a kind of bitter emptiness. It’s the emptiness of a person looking into himself all the time. But the objective world is always rich. There is always something around the next bend of the river. [p. 361]

Both books very highly recommended.

Postminimalism Takes Finland

The Fifth International Conference of Minimalist Music, in Turku and Helsinki (harbor above), Finland, was a smashing success. I ate sautéed reindeer and plenty of herring. We ended up Sunday night with only a few people left in the upstairs bar at the Torni Hotel, with Helsinki in the background (clockwise: my wife Nancy, Kay and Keith Potter, Dean Suzuki, Jonathan Bernard, Patrick Nickleson):

And here we are eating at the Sea Hors Restaurant: Dean, Nancy, Pwyll Ap Sion, Kay, Patrick, Keith, myself, and Jonathan:

A concert of mostly my music, including my Unquiet Night, Reticent Behemoth, The Unnameable, and Snake Dance No. 2, was presented at the gorgeous Music Centre building in the middle of town, its magnificent lobby shown here:

And I gave what I imagine is the first conference paper on the music of Elodie Lauten, whose reputation seems limited to New York; no one seemed to have heard of her. (I’ll put that paper up in this space soon, but it will take considerable reworking for non-oral presentation.) David McIntire spoke on Ann Southam, Frank Nawrot on Julius Eastman, Dean Suzuki on fine British postminimalist Andrew Poppy, Jedd Schneider on the surprising connections between Krautrock and American minimalism, and Dragana Stojanovic-Novicic on Conlon Nancarrow’s (generally negative) attitude toward, yet interesting connections with, minimalist process. Patrick Nickleson gave a fine paper on the curious ontological status of so much minimalist music, that it tends to not be score-based, but finalized by performance or recording, the score often constructed after the fact by someone other than the composer – with Marc Mellits’s Boosey and Hawkes score to Reich’s Music for 18 Musicians as the quintessential example. I told him that was almost my definition of Downtown music.

At the Finnish music panel I wrote down a slew of names of Finnish postminimalists to look up: Petri Kuljuntausta (whom I enjoyed talking with), Erkki Kurrenniemi, Jan-Olof Mallander, Pekka Jalkanen, Seppo Pohjola, Pekka Kuusisto, Adina Dumitrescu, Pehr Hendrik Nordgren, and of course Juhani Nuorvala, who co-directed the conference with John Richardson. None of us could make head or tail of the language. It seems that, despite some early appearances in Helsinki by Glass and Reich, minimalism and its offshoots have gained a foothold in Finland only in the last decade, largely thanks to Juhani’s efforts.

Here, waiting for the bus from Turku to Helsinki, are Justin Rito (whose paper was on David Lang), Joy and Andrew Granade just past him, Juhani with the glasses, and musicologist Robert Fink and wife in the back:

The Sixth International Conference is now tentatively scheduled for June of 2017 in Knoxville, Tennessee, in connection with the Nief-Norf festival run by Andrew Bliss. It gives me something to look forward to. The passage of my life is measured out in minimalism conferences.

Truly Music of the Spheres

When Pluto splashed into our collective consciousness last month suddenly ready for its closeup, I learned a lot I hadn’t known. For instance, that although the orbits of Pluto and Neptune overlap, they are prevented from colliding by the stable 2-to-3 ratio in their rotations around the sun; Pluto goes around the sun in 247.94 earth years, and Neptune in 164.8, and 247.94/164.8 equals 1.50449…. This kind of mutually influenced periodicity, as it turns out (how was I an astrologer for thirty years without learning this?), is common among pairs, trios, quadruples of planets, moons, asteroids, and so on, and is called orbital resonance. Three of the moons of Jupiter exhibit rotational ratios of 1:2:4, and there’s even an asteroid that has a 5:8 dance going with respect to the earth. This is truly the harmony of the spheres, the surprisingly simple mathematical relations that planets in a rotational system fall into in response to each other’s gravity.

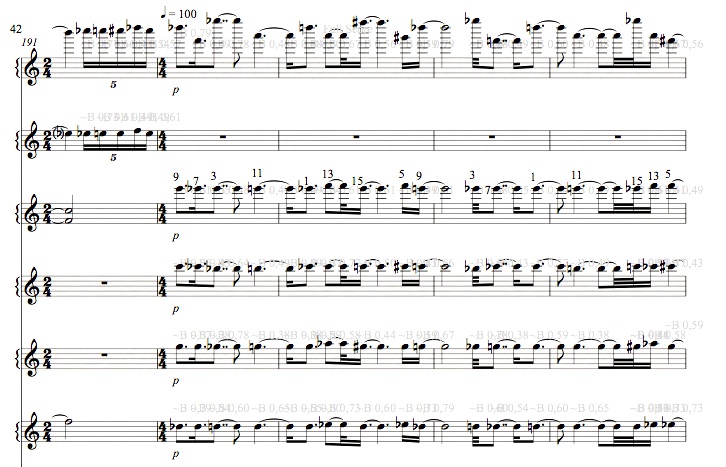

Chalk it up to my personal eccentricities that this suddenly gave me a whole new way to compose. I have an obsession with repeating cycles at different tempos, and it has sometimes been an aesthetic problem for me when the articulation points of those cycles coincide by chance. But the solar system, as it turned out, had been waiting with the solution all along. Inspired by this new knowledge, I realized I could use simpler ratios than I had been attempting (3:4, 5:6:7 instead of 17:19:23), but shift each one a slight amount so that the articulated beats would never coincide. It gave me a new way to create melody from the beats articulated among the different cycles. I immediately started a new piece, and five weeks later here it is, an extended pitch-and-rhythm study for three retuned Disklaviers:

Orbital Resonance (2015), 11:31

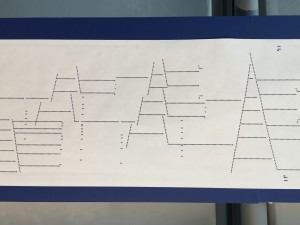

This is in what I call my 8×8 tuning, eight harmonic series built on the 1st, 3rd, 5th, 7th, 9th, 11th, 13th, and 15th harmonics of Eb, making 33 pitches in all. This is a complicated way to compose. First I had to write the piece for 17 pianos, one staff each, because I sometimes had 17 different pitch bends at once, and each pitch bend requires its own channel. After finishing the piece I had to figure out a workable retuning for three pianos to accommodate the 33 pitches. Next I had to map all those thousands of notes (sometimes in several different tempos achieved by tuplets) onto a three-piano score of six staves each. So I composed in something that looks like this (and if you can see all the little grayed-out numbers, those are the pitch bends on every note, along with harmonic series numbers so I could keep track):

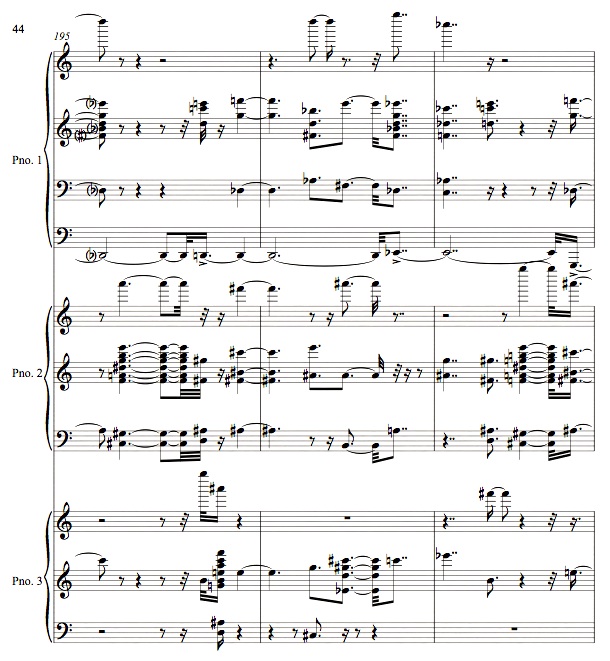

Then I transferred the notes to my three retuned pianos. The solution I came up with for distributing the pitches came out serendipitously. The harmonic series’ on 1 and 7 are mostly on piano 1, those of 11 on piano 2, and 13 on piano 3; the other harmonic series’ get divided up somewhat, but I use polytonal contrasts of 7, 11, and 13 a lot, so I tried to group those notes. It’s really not a piece for three pianos, but for one piano with 264 keys, but it could (after I’m dead and if someone ever wants to put the money into retuning three Disklavier grands) be played “live” on three pianos. And I like the fortuitous and wildly scattered way the sonorities bounce back and forth, like some whacked-out serialist extravaganza:

I think I can rest assured that no humans will ever attempt to play this. (If you look closely, you could find that, aside from the bass line articulating the 9-rhythm, there are always nine notes in every “simultaneity,”* and that the voice-leading is extremely chromatic; it’s pretty minimalist.) In order to get the kinds of rhythms suggested by the orbital resonance inspiration, I had to offset each cycle by a 32nd-, 64th-, or god help me 128th-note (I almost got used to double-dotted 16th notes) so that no points in the cycles would ever coincide. So it’s a sustained study in a quality of rhythm I’d never used before, and one which better allowed for melodic connections among the cycles. If you follow me. If you’re technically inclined I’ve got program notes that go further into the form, which is more logical than may appear on first hearing.

For years I’ve been trying to write something more elaborate both microtonally and polyrhythmically (and polytonally) than Custer and Sitting Bull (1999), and this is it: Nancarrow fused with Ben Johnston and La Monte Young with a dash of Piano Phase thrown in. (And by the way: this is not spectralist music, which approximates the harmonic series. This music actually employs the harmonic series, as Harry Partch, Ben, and La Monte were doing decades before the spectralists got started. The piece opens with the 65th and 66th harmonics of Eb and closes with the 54th, 55th, and 56th. Neither European 1/8th-tones nor Bostonian 72tet are sufficient for such distinctions.) I’ve got several other pieces for this setup started, and hopefully I’ll finish some of those as well. I’m hoping I might so well internalize the outlay of notes on the three pianos that I can skip the pitch-bend step and reduce the tedious part of the workload. There’s a PDF score on my score page if you’re technically intrigued. And as with Custer, I’ve dedicated the piece to Ben, who in 1984 started me down this incredibly labor-intensive road.

*I am a professor.

Don’t Shoot the Player Piano

Here’s an audience listening to a live performance of Nancarrow’s Study No. 25 at the Whitney Museum yesterday:

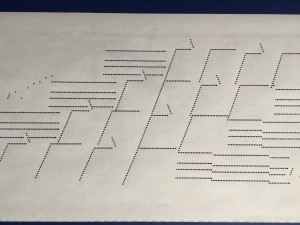

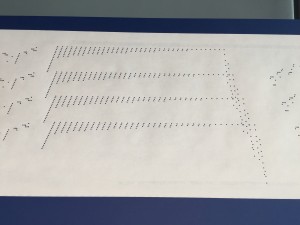

(As always, clicking on photos makes them appear in a new window in better focus. Don’t know why.) There was a player piano roll of Nancarrow’s Study No. 36 draped across one side of the room. Here are some high points:

And, via Susan Schied of “Prufrock’s Dilemma” blog fame, here I am standing in front of it. I had subconsciously chosen a shirt for the day that everyone thought was a player-piano-roll pattern:

High points of my evening took place at dinner with (L to R) Susan Schied, Liturgy guitarist Bernard Gann, his singer-girlfriend Heidi Farrell, my wife Nancy Cook, musicologist and Cage scholar Sara Haefeli, and one of those Pulitzer-Prize-type composers, John Luther Adams:

And in various other, more picturesque reconfigurations:

(Sara, who’s quite tall, is standing off the curb.)

Not pictured, unfortunately, because they’d already left: composers Mikel Rouse and Tom Hamilton, director of the John Cage Trust Laura Kuhn, and Nancarrow’s stepson Luis Stephens. Thanks to Jay Sanders of the Whitney and Nancarrow expert Dominic Murcott for involving me in a wonderful event.

An Embarrassment of Nancarrovian Riches

Several people have noted that I am mentioned in connection with the Nancarrow festival at the Whitney Museum this week. (I’ve been quoted in the Times and the New Yorker.) I will indeed be present for it next Wednesday, the 24th. At 1 PM and again at 4 I’m supposed to give an informal talk on Nancarrow, and bring up my favorite Player Piano Studies, which will then be played “live” on an Ampico player piano like Conlon’s. Sounds like a fun gig, but I can never decide which studies to play. The ones I wouldn’t play are easy to pick, but I always want people to hear nos. 3, 4, 6, 7, 20, 21, 24, 25, 27, 33, 36, 37, 40, 41, 43, and 48 and the unofficial roll M. It’s too much. I never know how to choose. No. 3 is so fun for the uninitiated, 4 is lovably cute, 6 is fun to explain, 24 is perfect, 25 is a riot, 40 is transcendentally exciting, 21 is a crowd-pleaser, 36 is a miracle, 37 is a modernist classic, 48 is hugely ambitious. I could do it all given enough time, but I never know where to start or stop. And I’ll have a dozen friends there to catch up with, including Luis Stephens, Nancarrow’s stepson by his second wife, who’s been an invaluable font of information about Conlon in the 1940s.

And to bring up another important composer, my friend John Luther Adams has a long excerpt from his upcoming memoir in this week’s New Yorker, in which he was kind enough to mention me. Good reading. John says I once told him, “John, you’re always so earnest, but I like you anyway.” John and I have been sober for a modest percentage of our times together. He greatly heightened my appreciation of expensive single-malt scotch, and I’ve never recovered.

Fear of Learning

The faculty is once again rethinking the distribution requirements, the obstacle course of varied classes every student has to take to make sure they all have a more well-rounded education than I do. So we’re having meetings about how to pitch courses to non-majors. I enjoy these. My colleagues in literature, the sciences, and the social sciences are so brilliant, so eloquent and thoughtful, that I’ve come to realize that I’m not all that smart – I’m just really smart for a musician. Today they asked what one thing I would want a non-music-major to get out of one of my classes. As so often happens, my mouth started rattling before my brain was even engaged, and what it said was good enough: “I want every student to realize that it is possible to fall completely in love with a piece of music that he or she didn’t like at all the first time they heard it.”

Because this is what I’m having a lot of trouble with. The closed-mindedness of some of my students seems like the worst thing about my life these days, and if that’s the biggest tragedy I’ve got to deal with, I guess I’ll survive. I’m talking about my composition students. I am prepared for our opera singers to turn up their noses at Stockhausen and Nancarrow, but these are young composers refusing to give modern masterworks a third hearing (actually, one of my singers is bugging me for the most dissonant Ives songs I can give her). I’ll play the Concord Sonata, or Bartok’s Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion, for a student, a music major, and they respond, “No no, I don’t like that, and I’m sure I never will.” Or I’ll play some astounding microtonal music, and they’ll say, “Oh, that just sounds out of tune, no one’s ever going to accept that.” No curiosity whatever, no openness, no wonder. Worse: it’s like, if they spend three hours listening to a 20- or 40-minute piece a few times, that’ll be three spoiled, precious hours of their life they’ll never get back. Or, maybe, if they learn to enjoy some peculiar-sounding piece, it will split them off from their peers, to whom they would have trouble relating the experience. I don’t get it. No one has ever called me un-opinionated, but when I was 18, I was going to be damned before I would admit that there was a piece of modern music in existence that I couldn’t understand. I’d listen to the same record a dozen times in a row until the piece started to make sense to me. I wasn’t committed to liking everything I heard, but I was going to understand every single piece well enough to understand why somebody liked it, even if I didn’t, and I was going to be able to articulate why, of all the complex and opaque pieces ever written, I’d decided I didn’t like this one. I withheld judgments for years, decades, until I felt I had done sufficient analysis to come to an opinion. After 20 years of full-time teaching, I’m still waiting to come across a student as totally committed to understanding the entire classical repertoire as I was at 18. Haven’t found one.

Part of the problem is that “the canon” carries no weight anymore (and little enough with me). Students come to school already knowing everything worth knowing, or so they think, having heard the first minute of thousands of mp3s, and with a calcified, corporate-determined idea of what is musically acceptable. With so many alternative histories of music available, why should mine be privileged? I like Giacinto Scelsi, but they like some hiphop artist I’ve never heard, so we’re even, right? But I’m the 59-year-old professor, and I can look back at the opinions I firmly held at age 20 with embarrassment and condescension. It alienates me from them. When they refuse to consider, despite detailed argument, that there may be incredible qualities in modern works that they haven’t understood yet, attempting to teach them becomes a tedious bore. What the hell are they in college for? Why am I baby-sitting people who aren’t impressed with my experience and opinion? Is this a generational thing? a product of iPod and internet culture? Why would smart, likable, upscale students be so determined that no one’s going to educate them?

And while I’m at it, get off my lawn.