The biggest tourist thing I did in Vienna was visit the Zentralfriedhof, the big cemetery where many famous composers (more than I’d realized from my research) and artists are buried, even though some of them were first buried elsewhere and then moved. So here are some photos. It seems silly to include so many photos of myself (taken by my wife Nancy), but after all, you can probably find most of the tombstones on Wikipedia, and the point is to prove I was there. (Click on photos for better focus.)

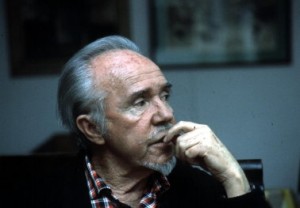

Here I meet the Great Man himself:

But here was where I got sentimental and weepy:

and with Johannes I felt a little confrontational (that damn lullaby, dontcha know):

Alex Ross told me to make sure I found Ligeti, and I did:

The monument is odd in that, if you look from the right angle, and only then, you can read his birth and death dates:

I’ve been told that Ligeti looked at my book on Nancarrow and pronounced the verdict: “Too American.” Thanks, György. Nearby was Ernst Krenek, whose name on the lower, flat rock has unfortunately become almost illegible:

Zemlinsky’s tomb, if attractive, was rather pretentiously jazzy, I thought, for someone whose music I usually find a mite turgid; there are some lovely songs and Die Seejungfrau is nice, but the Lyric Symphony has never impressed me:

I was surprised to run into Hans Erich Apostel, a name you don’t hear much these days (if indeed one ever did):

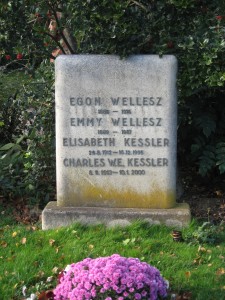

And also Egon Wellesz; I realized with a start that, for so familiar a name, I couldn’t remember ever having heard a note of the old man’s music, so while I was there I snapped up a disc of his 1st (unabashedly Mahlerian) and 8th (unconvincingly near-atonal) symphonies:

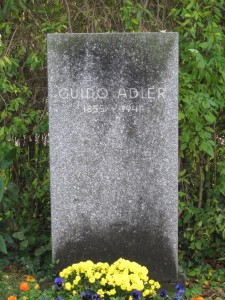

While we’re at it, Wellesz’s teacher the musicologist Guido Adler:

I actually fulfilled my threat of having my photo taken at Schoenberg’s tomb with a sign that read “LONG LIVE HAUER” – but I’m going to save that one for some future special purpose; it would give too much ammunition to all those who consider me the nefarious enemy of everything great in music.

I was amused to run across the arrogant-looking Franz von Suppé, whose Light Cavalry Overture I quote in my piece Scenario, so I do owe him something:

Gluck was there:

and Hugo Wolf, looking menacing despite the nude couple making out nearby:

Also Johann Nepomuk David, whose music I once had to write a program note for:

and Johann Strauss, whose waltzes I am fond of, though I found it inexcusably lazy that all the local Muzak systems relied solely on “Blue Danube” and “Wine, Women, and Song”:

His dad, too:

And to tell you the truth, one of the tombs I most wanted to visit was that of Franz Schmidt, whose chamber works and last two symphonies I’m very fond of (I hummed the Fourth the rest of the trip); I’m sure it’s supposed to be his muse, but the design suggests that he dreamed of scantily-clad young women, which I do too, but it’s not what I’d want to be immortalized for:

The only composers I had read were there and couldn’t find were Pfitzner and Czerny, but I’m not sentimental enough about either of them to consider the trip unfulfilling. I felt like I had seen enough of the old gang.