Composer and Sequenza 21 loiterer Steve Layton ran across this article pairing the two of us and discussing our gradual divergences from minimalism. It’s the kind of composer-centered thinkpiece that I didn’t think anyone wrote anymore except to praise Ligeti, Boulez, Adès, and that crowd that people praise to look cultured. Seems like old times.

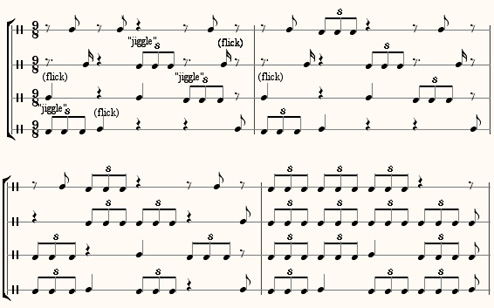

The most frequent and bitter complaint I’ve gotten about my book on Nancarrow over the years has been about the price. But I’ve just learned – over the

The most frequent and bitter complaint I’ve gotten about my book on Nancarrow over the years has been about the price. But I’ve just learned – over the