Pianist extraordinaire Sarah Cahill, whose browser somehow won’t let her interact with Arts Journal comments pages, nevertheless chimes in on the dynamics issue:

Leo Ornstein… was an excellent pianist himself, and wrote fabulously for the piano. But most of his piano scores have absolutely no dynamic markings whatsoever. He believed that it was the pianist’s responsibility to come up with dynamics in the process of interpretation. It’s so interesting, because there will be a passage which to one person is a climax, to be played forte, and to another person it will be an opportunity to back off and have it be more powerful as a pianissimo passage. So his scores can be played in a variety of ways, and it’s fascinating to hear different performances.

…[W]hen a piece leaves dynamics out, it makes us as performers explore it in an entirely different way. We can’t rely on superficial expression (playing dynamic markings as notated), we have to dig deeper and get to the heart of the piece to figure out what’s going on, how to best interpret it, and how dynamics figure into that interpretation. It can be a more satisfying experience.

Not that everyone should compose the way Ornstein did – but if someone’s imagination works that way, why shouldn’t he be allowed to do it? How did conformity become such a cherished attribute among composers? And I can’t resist re-quoting the following note that Ellen Zwilich appended to her Lament for piano of 1999, a warning that Chopin would have found ludicrously obvious, but that today’s notation neuroses have made necessary:

Throughout, whether the passage is marked liberamente or not, the performer should feel free to ‘sculpt’ the rhythm and dynamics for expressive purposes in order to give a spontaneous, improvisatory quality to the piece. It would be ideal if no two performances were exactly alike.

The most frequent and bitter complaint I’ve gotten about my book on Nancarrow over the years has been about the price. But I’ve just learned – over the

The most frequent and bitter complaint I’ve gotten about my book on Nancarrow over the years has been about the price. But I’ve just learned – over the

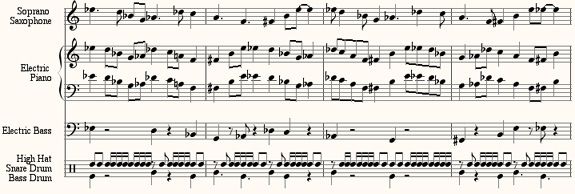

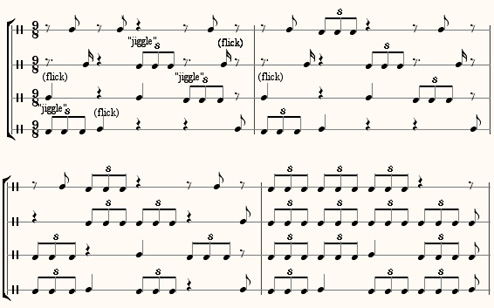

I had never heard Mosko’s music, but was well aware of his activities as a conductor. I once reviewed his Newport Classic recording of Feldman’s For Samuel Beckett as being the best available. Last week Art Jarvinen was kind enough to send me the O.O. Discs CD of Mosko’s music, performed by the California Ear Unit, and he tells me there’s a hard-to-find one on Cambria as well. I had no idea what to expect. Mosko’s music is thorny – or gnarly, in the parlance of our time – but his time sense is distinctive. Even when the music’s individual gestures are quick, it sustains its focus for many moments in succession, and changes slowly. It is quasi-atonal in a way that allows tonal passages to happen in a non-quotation-like way, almost as if it simply makes no distinctions among sonorities. Therefore it is playful rather than tense, with highly soloistic instrumental writing, and reminds me, more than anyone else, of Stefan Wolpe’s music. There is much stasis, dotted by delicate bursts of activity that build up no momentum. His early influences include Webern, Feldman, Cage, Icelandic folk music, and Sufi music, the first three more evident than the others.

I had never heard Mosko’s music, but was well aware of his activities as a conductor. I once reviewed his Newport Classic recording of Feldman’s For Samuel Beckett as being the best available. Last week Art Jarvinen was kind enough to send me the O.O. Discs CD of Mosko’s music, performed by the California Ear Unit, and he tells me there’s a hard-to-find one on Cambria as well. I had no idea what to expect. Mosko’s music is thorny – or gnarly, in the parlance of our time – but his time sense is distinctive. Even when the music’s individual gestures are quick, it sustains its focus for many moments in succession, and changes slowly. It is quasi-atonal in a way that allows tonal passages to happen in a non-quotation-like way, almost as if it simply makes no distinctions among sonorities. Therefore it is playful rather than tense, with highly soloistic instrumental writing, and reminds me, more than anyone else, of Stefan Wolpe’s music. There is much stasis, dotted by delicate bursts of activity that build up no momentum. His early influences include Webern, Feldman, Cage, Icelandic folk music, and Sufi music, the first three more evident than the others.