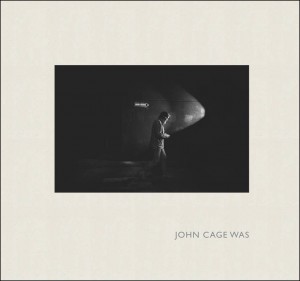

I am in receipt of James Klosty’s handsome new coffee-table volume John Cage Was, a book of photographs of John Cage, many of them rare and unseen before, all of them telling. For the margins Klosty asked a lot of people connected with Cage to write descriptions of him of a hundred words or less, using the words “John Cage was….” For those who are unlikely to shell out for the book, here’s what I wrote:

I am in receipt of James Klosty’s handsome new coffee-table volume John Cage Was, a book of photographs of John Cage, many of them rare and unseen before, all of them telling. For the margins Klosty asked a lot of people connected with Cage to write descriptions of him of a hundred words or less, using the words “John Cage was….” For those who are unlikely to shell out for the book, here’s what I wrote:

John Cage was the figure who, for thousands of musicians, opened the door to the world beyond rationality. By introducing us to the I Ching, and showing us how to use it both artistically and practically, he made it seem safe and creative and irresistible to explore not only Eastern thought and Buddhism, but astrology, Tarot, Jungian theory, and any discipline based in an ineffable synchronicity. He freed us to not understand what we were doing, and making art has been more interesting ever since.

In college I did indeed spend years consulting the I Ching, though I found it rather opaque, and never settled into it well; it seemed to be forever telling me that “it furthers one to cross the great water.” In retrospect, I guess it was directing me to expatriate to Europe posthaste, and I wish I’d complied. Tarot cards (which Cage used in composing 4’33”, though no one knows how) I found attractive, and still do, but wasn’t intuitive enough to interpret them with any subtlety. Astrology was the synchronicity system that clicked with my mathematical brain. I once consulted with Cage’s astrologer, Julie Winter, and many of the books I read on astrology early on were by another composer whose music I am devoted to, Dane Rudhyar. The new-agey/occult side of Cage’s influence gets whitewashed from his public persona, but for some of us it was explicit.