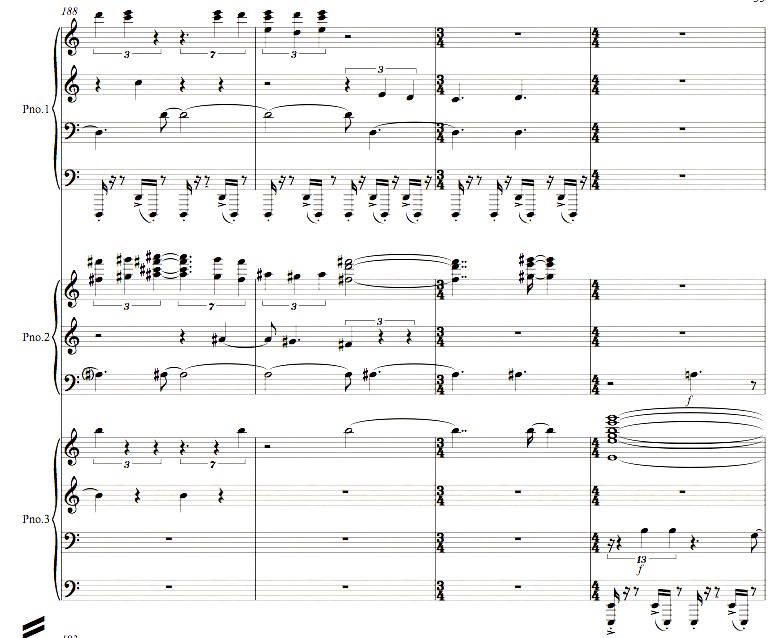

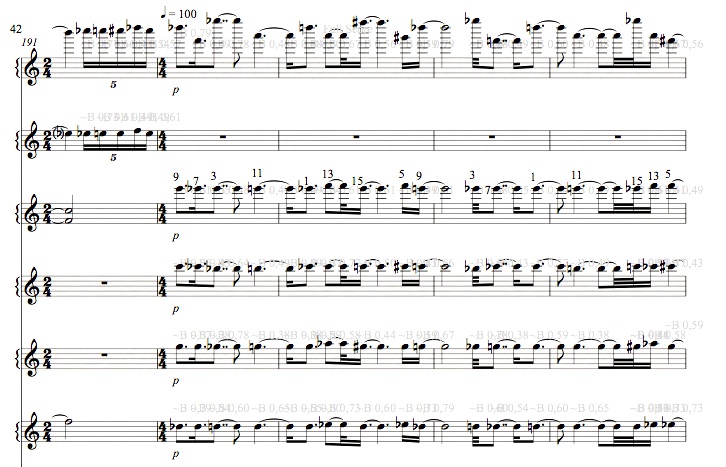

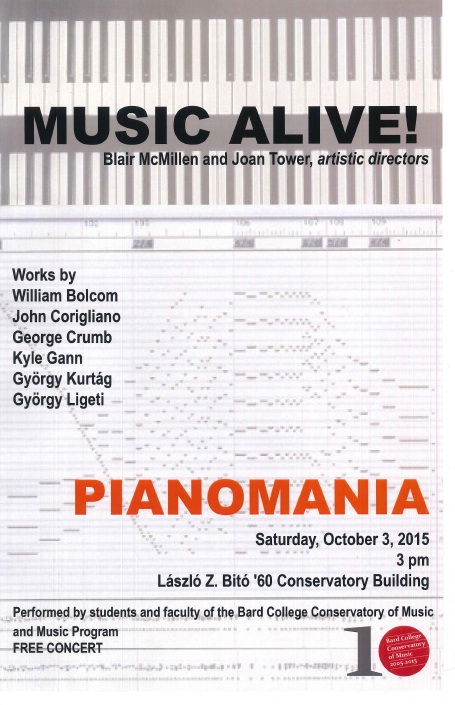

I’ve got a performance coming up at Bard College [where I teach] this Saturday. My office Disklavier will play my Bud Powell homage Bud Ran Back Out, and famous composer Joan Tower, no less, is slated to play the second dance, “Sad,” from my Private Dances. As you can see from the accompanying poster, Kurtág, Corigliano, Ligeti, and I are making a once-in-a-lifetime appearance on the same program. If it weren’t for Crumb and Bolcom I’d feel a little out of place. The MIDI graphic on the poster is a section from my Nude Rolling Down an Escalator, taken from my eponymous CD cover.

I’ve got a performance coming up at Bard College [where I teach] this Saturday. My office Disklavier will play my Bud Powell homage Bud Ran Back Out, and famous composer Joan Tower, no less, is slated to play the second dance, “Sad,” from my Private Dances. As you can see from the accompanying poster, Kurtág, Corigliano, Ligeti, and I are making a once-in-a-lifetime appearance on the same program. If it weren’t for Crumb and Bolcom I’d feel a little out of place. The MIDI graphic on the poster is a section from my Nude Rolling Down an Escalator, taken from my eponymous CD cover.