I’ve built up quite a backlog of unheard music, and now after a long dry spell it’s beginning to flow public-ward again. On December 7 Michelle McIntire sang a pre-premiere of most of my Ezra Pound song cycle Proença (five songs out of the six) at Missouri Western State University, and I’ve got recordings! Here are the three that I thought came out best:

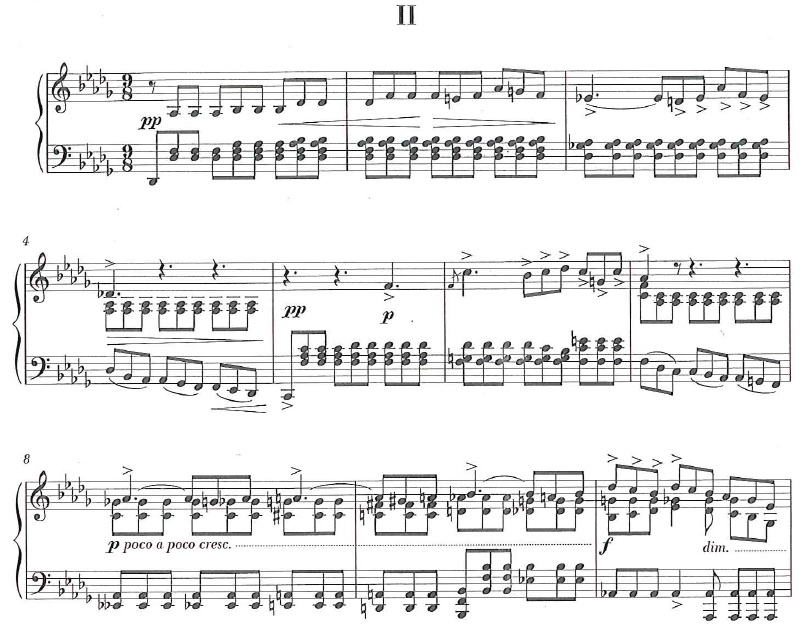

2. Na Audiart (7:05)

3. Alba (En un vergier sotz fuella d’albespi) (5:14)

5. L’aura amara (8:47)

The first is a poem by Pound about Bertrans de Born; the others are Pound translations of troubadour songs. The performers are:

Michelle Allen McIntire: voice

Virginia Q. Backman: flute

Jennifer Wagner: vibraphone

Jennifer Lacy: electric piano

Brian Padavic: electric bass

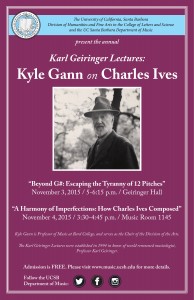

and the recording is by Jon Robertson, who will be recording engineer next summer when they produce the whole cycle (50 minutes) for David McIntire’s Irritable Hedgehog label. The group was going to give the official premiere in Kansas City on February 13, but that’s the night I’m at Illinois Wesleyan University for the premieres of my Implausible Sketches and Transcendentalist Songs. So they’re going to try to delay by a week, and they’ll also play the piece at Bard College soon after, probably in early March. I’ll give all the details when known. I am, among other things, the vocal-music composer at Bard, with choral pieces, operas, and more than two dozen songs in my output, and it’s great to finally get that music out there. Thanks to Michelle and David and the others for their tremendous dedication. They’ve been rehearsing weekly for months.