Roscoe Mitchell — internationally renown composer, improviser, ensemble leader, winds and reeds virtuoso who has pioneered the use of “little instruments” and dramatic shifts of sonic scale in the course of becoming a “supermusician . . .someone who moves freely in music, but, of course, with a well established background behind . . .”* reveals […]

Electroacoustic improv, coming or going? (Herb Deutsch, RIP; synths forever?)

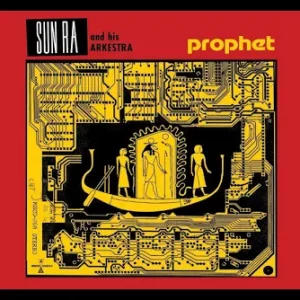

As the year ends/begins, I’m thinking electroacoustic music is a wave of the future. But maybe it’s been superseded by other synth-based genres — synth-pop, EDM, soundtracks a lá Stranger Things. Is Prophet, the just released 1986 weird-sounds bonanza from Sun Ra with his Arkestra exploiting the then new, polyphonic and programmable Prophet-5 synth, timeless […]

Tania Leon interview 1989

Tania Leon, 2021 winner of the Pulitzer Prize for music composition, has not often been interviewed in the popular press, so here’s a Q&A I conducted with her as published in 1989 by Ear magazine, and Jeremy Robins’ 2007 Composers Portrait of her, commissioned by American Composers Orchestra. Tania Leon, Assistant conductor of the Brooklyn […]

Record man Koester’s blues and jazz legacy

Chicagoan Bob Koester, proprietor of the Jazz Record Mart and Delmark Records for nearly 70 years, is a model of music activism and entrepreneurship from an era rapidly receding and unlikely in current business circumstances. Neil Genzlinger did a nice formal New York Times obit, and I’ve written a remembrance for the Chicago Reader. Although […]

International Jazz RIPs, 2017

Photographer-writer-author Ken Franckling has painstakingly compiled a compendium of more than 400 jazz artists and associates from around the world who died in 2017, with links to obituaries of most of them. Posted at JJANews.org. It’s a striking document and useful resource, though Franckling says, sadly, “The list seems to get depressingly longer each year.” Maybe that’s […]

Last glance 2010: great performances and best beyond jazz

There’s not much time left, so here are three of my best memories of live music over this crazy year, and a couple handfuls of favorite recordings that promise to be listenable for quite a while forward —

AACM at 45: “Creative Musicians” span generations, U.S., globe

The AACM — Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians — continues after 45 years to encourage highly original, edgy and exciting artists — as I detail in my new City Arts column. Examples in New York City: reedist/composer Henry Threadgill’s Zooid performs tonight and tomorrow at Roulette; trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith’s 22-piece Silver Orchestra and the […]

Jazz elders cast giant shadows

Why isn’t the amazing current generation of creative (jazz) musicians better known? Maybe because major artists of the not-so-distant past are practicing the art form at splendid peaks, overturning clichés about dwindling powers of octogenarians. Read my column in City Arts New York for a report that touches on Sonny Rollins, Roy Haynes and Muhal […]

Fred Anderson, Chicago jazz hero, appreciated

As a teenager in pursuit of the avant garde, I took tenor saxophonist Fred Anderson, who died June 24 at age 81, as a hero upon first hearing him in 1966. It was at a Unitarian Church-run coffee house in downtown Evanston near Northwestern U., and attention clearly had to be paid to the long, fierce, unreeling, knotty […]

Visionaries photo’d at NEA Jazz Masters concert

Just in — Â Muhal Richard Abrams conducting the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, and Yusef Lateef on tenor sax with percussionist Adam Rudolph, fine performance photography by Frank Stewart from the National Endowment for the Arts’ Jazz Masters concert. My post on the concert is here, and the images are below —

Beyond “jazz” conventions from NEA Jazz Masters

Jazz, defined by creativity, pushes boundaries — a fact alluded to and demonstrated by two of the new NEA Jazz Masters at the gratifying if lengthy ceremony and concert held at Rose Theater of Jazz at Lincoln Center on Tuesday, Jan 12. Muhal Richard Abrams and Yusef Lateef were inducted into the canon that now […]

Wynton & Orch play NEA Jazz Masters, on radio tonight!

Just announced: WBGO, NPR and Sirius/XM are broadcasting live and streaming on the web tonight’s NEA Jazz Masters ceremony and concert with W. Marsalis and the LIncoln Center Jazz Orchestra performing works by Muhal Richard Abrams, Bill Holman, Bobby Hutcherson et al. Pianist Cedar Walter will perform with singer Annie Ross, Kenny Barron will play […]

Hurray for the new NEA Jazz Masters

Dean of post-jazz Muhal Richard Abrams,  doyenne of vocalese Annie Ross and George Avakian, who invented jazz albums and reissues, popularized the LP and live recording, are among eight 2010 Jazz Masters named today by the National Endowment of the Arts. New York-based pianists Kenny Barron and Cedar Walton, exploratory reedist Yusef Lateef, big band composer-arranger […]