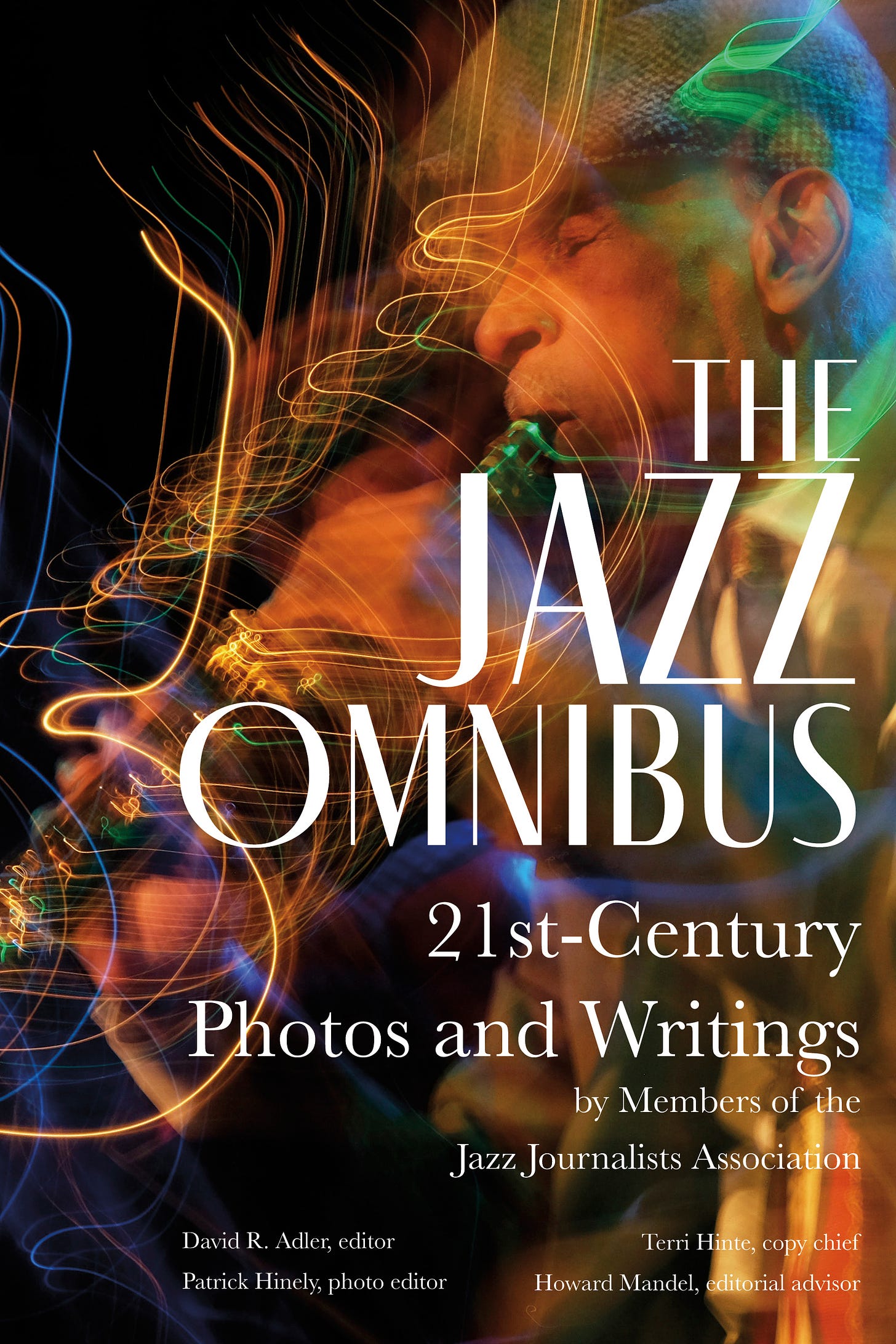

I’m proud of my two published books (Miles Ornette Cecil – Jazz Beyond Jazz and Future Jazz) and my unpublished ones, too; the two iterations of the encyclopedia of jazz and blues; I edited, and my collaborations with some musicians creating their own books — but right now I’m crazy enthusiastic about The Jazz Omnibus: 21st-Century Photos and Writings by Members of the Jazz Journalists Association,

published in e-book, softcover and hardbound formats by Cymbal Press, most readily available from you-know-where. So crazy I’ll brazenly go all advertisements-for-myself to promote it. Here’s the story :

Six-hundred pages of profiles, portraits, interviews, reviews, inquiries and analysis of music, all from the past 20 years by dozens of the people far and wide who make it their business to cover jazz in its multifarious, ever-permutating forms. Created by a team comprising editor David Adler, photo editor Patrick Hinely, copy chief Terri Hinte, me as editorial consultant and readers Fiona Ross and Martin Johnson,, with a dazzling cover photo by Lauren Deutsch (of Roscoe Mitchell, from her “Tangible Sound” series), and dedicated to the memory of JJA emeritus member Dan Morgenstern (1929-2024) The Jazz Omnibus strikes me — involvement admitted! — as unique and multi-dimensional.

It doesn’t claim to be a comprehensive history yet it provides a sweeping overview of the topics addressed by music journalists, with many different perspectives conveyed in words and pictures. It offer newcomers numerous entry points, introductions to emerging artists as well as in-depth discussions of icons. Connoisseurs will find plenty to argue about as well as some work they’ve probably never come across before.

What’s great about this anthology is the diversity of voices and viewpoints focused on the incredibly resilient creative expression we call jazz (acknowledging that some practitioners reject the term). There is been nothing quite like it in the jazz literature — most anthologies represent a single writer or photographer’s pieces. Here we’ve got Ted Panken, Paul de Barros, Suzanne Lorge, Nate Chinen, Ted Gioia, Willard Jenkins, Enid Farber, Bob Blumenthal, Bill Milkowski, James Hale, Larry Blumenfeld, Jordannah Elizabeth, Ashley Kahn, Luciano Rossetti — observers immersed in their subjects. DownBeat’s The Great Jazz Interviews is similarly valuable, as is The Oxford Companion to Jazz (I’m in that 2004 anthology, writing about jazz to and from Africa), but I daresay The Jazz Omnibus is more freewheeling and multi-faceted.

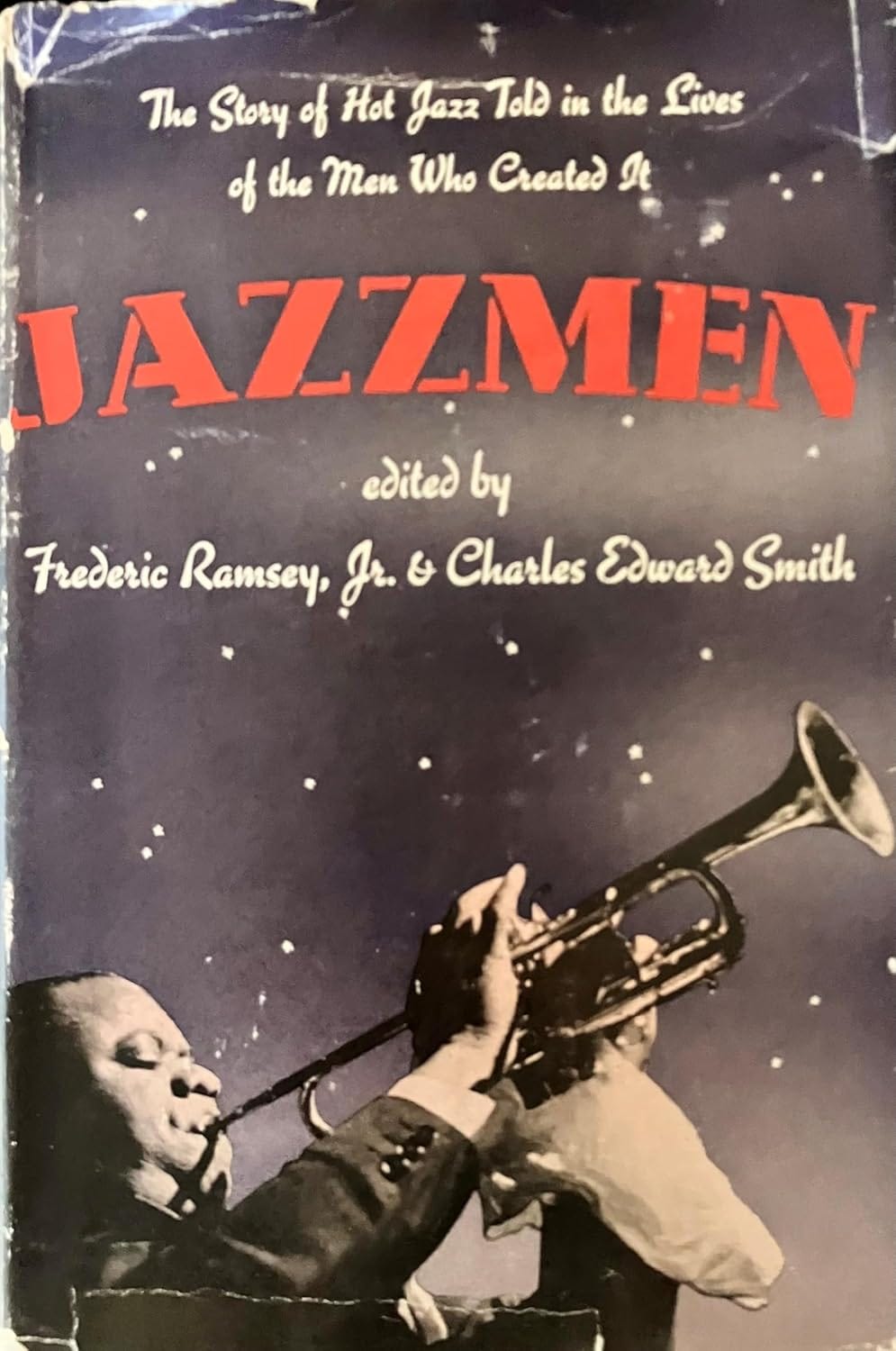

In its early gestation I thought of it as a descendent of two volumes I’d loved as a child: This is My Best and This is My Best Humor (now completely disappeared) both edited by Whit Burnett, founder of Story magazine (founded in 1931, ongoing). There’s also been Da Capo’s Best Music Writing series, but it was far from jazz-centrric and ended 13 years ago. Jazzmen, regarded as first jazz history book published in the U.S. (in 1939), also featured chapters contributed by nine writers. It’s gratifying to have The Jazz Omnibus join such a literary lineage.

The Omnibus is, of course, central to the mission of the JJA — which you may well not know, is a New York-registered non-profit of some 250 internationally-based writers, photographers, broadcasters and new media professionals, networking to sustain ourselves as independent disseminators of news and views of jazz (as on our website JJANews). I’ve been president since 1994. We incorporated in 2004. Even before then, we’d established annual Jazz Awards for altruistic and journalistic as well as musical accomplishments; these continue. We’re media-forward, running monthly “Seeing Jazz” photographers’ sessions archived on YouTube, producing the podcast The Buzz, having experimented

with multi-platform and virtual reality online events, staging a guerilla video campaign called eyeJazz. We run almost entirely from members’ dues, although creation of The Jazz Omnibus has been supported by Berklee Institute of Jazz and Gender Justice, the Jazz Foundation of America, and the Verve Label Group (Verve, Impulse! and Blue Note Records). The JJA will benefit from royalties from the book’s sales.

In the early 1990s, when my friend and colleague Art Lange was JJA president, the organization produced two collections of members’ writings, mimeographed, Xeroxed and stapled, a la fanzines. These were just meant for us, the members. The Jazz Omnibus doesn’t claim to represent the totality of jazz, but it’s intended to be broadly accessible and appealing, Meant for everyone. As is “jazz.”

End of shameless self-promotion — for now. You got this far: Please see The Jazz Omnibus!