PLATFORM 2016: A Body in Places (February 17-March 23).

Eiko performing in Precarious II: Guest Solos in PLATFORM 2016: A Body in Places at St. Mark’s Church. Front right: Beth Gill. Photo: Ian Douglas

Did you happen to see Eiko in the summer of 2014 when she danced in Fukushima, Japan, the site of the fallible nuclear plant damaged in the 2011 earthquake and the terrible consequences to the people and the territory around it? Or on Governor’s Island that same summer? Did you see her in Valparaiso, Chile this past January? Maybe you came across this kimono-clad Japanese woman with long, black, gray-streaked hair in the subway hub of New York City’s Fulton Center or lying on the floor of Philadelphia’s 30th Street station. She would be pale-faced, fragile in appearance, but strong of soul and intent.

If you’re above a certain age, you might have seen Eiko and her partner Koma in 1976, performing their White Dance in a very small area of space in some Manhattan studio. They called it “an avant-garde dance in the Japanese manner.” They moved at a snail’s pace. They quaked and opened their mouths wide. They were alarming and strangely beautiful, and they had come to live among us, raise a family here, become part of the scene.

For the past several years, Eiko has been performing without Koma (who is recovering from a severe ankle injury). And from February 17 through March 23, she has, together with Judy Hussie-Taylor and Lydia Bell (Danspace’s executive director and program director respectively), organized Danspace Project PLATFORM 2016: A Body in Places. It presents solos by Eiko and others, Talking Duets, Delicious Movement Workshops, films, book club meetings, discussions, and an installation (details at: http://www.danspace.org). In a conversation with colleagues found in the treasure trove of a catalogue, she says, “Now I don’t want to dance in a space, I want to dance in a place.”

This is not entirely new. Eiko and Koma have danced up to their waists in rivers, tangling with branches. They drove an ingeniously re-vamped caravan into city parks around the U.S., opened it up, and performed in and around it (a version of this was performed in the main lobby of MOMA). But they also transformed theaters—standing in eerily lit pools of shallow water, merging with the roots of a giant phantasmagorical tree, showering the floor with rice.

Often they resembled not just human beings groping their way together through often hostile landscapes, but forces that moved together or apart like tectonic plates or vines that twisted around structures. Always, they drew out time; you could watch, mesmerized, while one of them slowly, slowly lifted an arm from the huddle where they lay. Where would it go? When would it land?

Eiko in the Church House at Middle Collegiate Church in a preview of one of her solos, during A Body in Places. Photo: Lily Cohen

Eiko alone doesn’t have the possibilities for creating the kinds of abstraction and transformation that she and Koma together had. She is a woman in a place, and she makes you regard whatever place she investigates with new eyes. On Wednesday, February 24, she performed a preview of solo #3, scheduled for March 2. A group of us check in on the steps of St. Mark’s Church-in-the- Bowery and walk down Second Avenue from 10th Street to the 7th street side entrance of Middle Collegiate Church. We go at a fairly good clip (it’s raining lightly). These are blocks I know well, having walked along them for years to NYU-Tisch School of the Arts. I see the neighborhood partly as a palimpsest, since the kosher deli where we faculty once gathered, the Chinese restaurant that had the best cheap soup, and the second-hand furniture shop where I bought an old chest are gone. The empty storefront, where I use to eat noodles and watch a video about the history of noodles, vanished in a devastating explosion months ago; people pause to read the tributes hung on the chain link fence that honor the two young men who died.

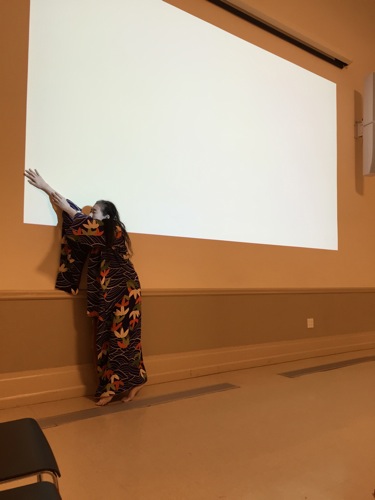

Eiko is already lying on the floor when we enter a large, high-ceilinged area with a balcony on three sides—plain and utilitarian. At one end a huge white rectangle on the wall waits for a film to be projected onto it. Or just waits. We sit in a single semi-circle of chairs to watch Eiko, wearing a dark blue, flower-printed kimono, lying on the floor. She could be sleeping. It takes her a very long time to roll almost over and then return to her original position. Eventually her gaze takes in the space, then us (after rising, she comes very close to a few people). She lashes a piece of red fabric in arcs, then fits her body and reaching arm to conform to, or counterstress one edge of that empty white rectangle. If she performed some of these actions at an everyday tempo, you might take her for an interior designer measuring the space and determining what it needed.

Eiko in the Sanctuary of Middle Collegiate Church. Photo: Lily Cohen

After a while, she implies that we should follow her down a short corridor and through two doors. A revelation! From a rather functional space, we’ve entered the Sanctuary of this gothic structure (whose façade we’ve not yet seen). This third incarnation of the 18th-century Middle Collegiate Church was erected on the site in 1892. The New York Liberty Bell in its tower rang to celebrate the signing of the Declaration of Independence in 1776. The splendid interior is all dark wood, stained glass windows, and a hushed glow of light. Eiko explores it with very minimal movements, while we watch from the pews. A large transparent bowl of water hints at baptism; she washes her hands in it, carries it carefully, sets it down on the floor. She positions herself along a side wall, inches between the benches.

I think, as I have many times before, how she often she wants to appear wounded or feeble. In the catalogue, she says something revealing in relation to the earlier Fulton Center performance: “I presented myself as very weak and broken, and I wanted to do that because I get very irritated by someone who is healthy. It’s like people that have money; they don’t know the situation of people who don’t have money. . . .And I was never a physically capable person. I look at the world through that perspective.”

Eiko on Second Avenue for the last part of her solo. Photo: Judy Hussie-Taylor

There’s another shock. We follow her toward the main entrance and out through the door she opens. Suddenly we’re in the bright, damp afternoon clamor of Second Avenue. She has taken off her kimono to reveal a blouse and sarong. She whips the kimono around and, disregarding a large red Coca Cola truck parked to one side, steps into a puddle of rain water that has gathered in one of Second Avenue’s curbside potholes, and stamps it to splashing fervor. People—not many— walk by, look, whisper, walk on. This is New York, right? Art happens. Eiko bows, smiles, and walks away. Next time I’m across the street from that church, I look at it. And see it.

Beth Gill and spectators in the earlier Precarious I: Guest Solos of DANSPACE 2016: A Body in Places. Photo: Ian Douglas

On March 5, the far plainer St. Mark’s Church opens its doors from 7 P.M. to 10 P.M. for another PLATFORM 2016 event—Precarious II: Guest Solos. Enter any time, leave, come back if you like. You’re handed a map designating where and when eight soloists will be performing. It’s a bit like a treasure hunt, except that no one wins, and treasures are not hard to find (although seeing them may require good timing and strategies).

You can always locate Beth Gill, even though she’s wearing knitted pants and a top whose beige tone comes close to blending the gray carpeting on the risers that she rolls and crawls along, slides down from, and works her way back onto, hardly ever standing up. Inspired by a years-ago viewing of Husk (1987): Eiko filmed by Koma in a pile of leaves, Gill moves slowly and sensuously, feeling the shape and texture of the surfaces she crosses, yielding softly to gravity. Spectators make way for her. Or not. She began at 7 o’clock; I imagine she’ll have worked her way back to her starting point by 10.

Koma Otake performing Dancing with My Painting and Lion outside St. Mark’s Church. Photo: Ian Douglas

At 7:30, outside the front door, Koma Otake gives the first of his three performances that night of Dancing with my Painting and Lion. Initially, it involves a struggle. Koma, wearing a loose black overcoast, positions himself belly-down over a stool, from which wires extend to his black stain of a painting. As he jolts his way toward the artwork, the wires slacken, letting it gradually crumple and descend to the floor (later he will make it rise again and weigh down the stool with a sandbag. Although still recovering from that injured ankle, Koma dances expansively over the sand-sprinkled paving stones, enjoying the rhythms of the tango that he sets playing. His gestures have a wild freedom to them, and his gaze takes in the architecture of the portico. He acknowledges one of the two stone lions that guard the entrance to the church. The coat comes off, revealing an inside-out kimono, and then is donned again and wielded as if it were the skirt of a grand dancer. (I think of a solo by Eiko and Koma’s early teacher in Japan, Kazuo Ohno, and his homage to Antonia Mercé, Admiring La Argentina).

During my time in the church, I barely glimpse two of the events. The spectators fill the doorway into the priest’s room, and I can’t see much of Arturo Vidich, who has rigged chimes to hand-held frames and strikes them as he moves in the confined space, alluding to the bells that call the parishioners to church. I catch Geo Webb as I pass through another door and climb to the choir loft, or hang out in the small dressing room, where the restroom, its door left open, is bathed in an ominous blue-green light. At various times, Webb lugs chairs, benches, and an ironing board into what could be called arrangements and rests in them. He catches someone taking notes and peers po-faced at what she’s written. When I’m not in that room, I often hear laughter.

Arturo Vidich performing in the Priest’s room. Photo: Ian Douglas

Upstairs, on the balcony that extends along the church’s eastern end, Neil Greenberg periodically consults a laptop, perhaps deciding which brief excerpts from various earlier works to perform. Occasionally he revs himself up for a new stint by clasping his hands and rocking his arms from side to side. This man can be a space-devouring mover (although he’s always thoughtful about it). He may swoop down the length of the balcony, throwing his arms in ways that seem to pull his feet along. He does a passage that’s all about vehement kicks of one leg or another (not pretty kicks, ones that could send a football sailing). Occasionally he (and we) over the rail, down to where Eiko may be moving slowly and Gill continuing her trip.

Back in the sanctuary, I pause to watch Boulé in one of her presentations. She’s got music coming out of a tiny player, and, to a “re-edit” by Theo Parris of The Dells’ “Get on Down,” she’s performing her Unravel the Monomyth—treading rhythmically from foot to foot with a kind of elastic grace. Sometimes she smiles gradually, then lets the smile fade.

Expecting to come back, I move on to the Parish Hall, where people have already. The papers arranged on the floor to one side I later discover to be Jimena Paz’s notes and drawings relating to a dance, Romancero Gitano, that, twenty-five years ago, she was beginning to learn from her teacher in Argentina, Iris Scaccheri, when a scholarship to study abroad cut short the process. Today Paz is not performing Scaccheri’s dance, but the one she has gleaned from her notes. Eiko, who has returned from lying near the exit to the graveyard, lies on the sidelines, once reaching out an arm toward Paz. (I learn of a frail connection later. Scaccheri had studied in Germany with Dore Hoyer, who had danced with Mary Wigman; much later, Eiko and Koma studied in Germany with another Wigman dancer, Manja Schmiel).

Jimena Paz performs in the Parish Hall at St. Mark’s. Photo: Ian Douglas

Like the other performers in PLATFORM 16: A Body in Places, Paz makes you ponder the space—its irregular shape, the light coming from the high windows, the two columns, the big fireplace with iron doors—-not because she communes with them, but because she explores the room as if it were haunted, as if she saw things we didn’t see. Paz, who danced in Stephen Petronio’s company for seven years, has long, articulate legs and beautifully arched feet. She roams the space, spinning along its paths, taking big steps and lancing herself into deep lunges. Every now and then she strikes a pose, standing on one leg with the other lifted high behind her, in front of her, or to the side. Although this may sound balletic, believe me, it isn’t. And she waits in each pose, sometimes deepening into it, for what seems like a long time. Maybe she’s waiting for a memory to develop. At some point Eiko, lugging a bundle of fabric, slides down a wall to sit and watch, then sinks deeper, maybe even naps.

It’s almost 9:30. I reenter the sanctuary, get my coat and hat off the rack by the main entrance, and prepare to leave. Eiko has evidently also been thinking of exiting. She takes a couple of tired- looking white chrysanthemums (big ones) from a vase, and, with some difficulty, props both doors partly open with her arms, feet, and body (she sprained a wrist days ago, and it’s heavily bandaged). She buries her face in a white flower and then looks at us. A few thin petals hang from behind her upper lip, so that, for several startling seconds, she looks as if she has sprouted small fangs. She bites off more petals and spits them onto the floor. Now she comes very close to me, and we stare at each other. I hold out my hand. She puts a small clump of petals in it and moves toward another person. I decide to let the petals join the scattered snowfall of them on the floor. Waiting for the crosstown bus, I smell my hand. That sweet, slightly musty fragrance lingers, as do images of dancing imprinted on a church whose cornerstone was laid in 1795 on land that had had a small family chapel on it since 1660 when New York was New Amsterdam and we all spoke Dutch.

It is with pleasure that I was introduced by my friend António Laginha to these Japanese space dancers. I’m an architect and as so my mind is arranged in a way that I look to any place and capture it’s soul. We describe this information “genius locci”, place’s and space’s spirit. But as I read your article I became aware about the wizard Japanese Dancers, Eiko and Koma, that seem to fold spaces with their performances. This is something different. As I entered more inside the text my mind vanished into emptiness. As so It is possible that these two fascinating artists, which you describe so beautifully, came across the divine architect of the universe, God himself. And in this way, as they perform, our minds become quietly in peace and you can see a glance of the skies. Better than to go to church is to know about people that have the divine weapons of God in the form of creativity. They offer more understanding, knowledge and peace than a priest. This is not religion. This is life as a whole. This is true happiness. Thank you for your most pleasant writing. It made me happiest.

FUNNY, I’ve missed most of Eiko and Koma though I did hear she was dancing alone. This is a nice picture of what she does and has been doing all over the world. Places vs spaces. Venues vs theatres, water vs land. They seem to have covered them all and dance is their medium. What I know most about them , the strangest thing of all, is that the great jazz Empressario (sic) Mura Dehn, who traveled all across Europe from Russia to follow her dream of dancing to jazz, and even better, filming it at the Savoy int he most beautiful abstract black & white footage, left Eiko and Koma to dispose of her archives. I don’t know the connection, but there had to be a strong one for them to get together and have the ol US as their inspiration.