Seeing Things

TOBI TOBIAS on dance et al...

Sunday, January 30, 2005

RAIN DATE

New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, NYC / through February 27, 2005

Christopher Wheeldons After the Rain is the new ballet thats making news in the New York City Ballets winter season. One of Wheeldons bare-bones works, its set to a pair of unrelated short pieces by Arvo Pärt, the Estonian composer given to spare constructions in grave moods who is so appealing to todays choreographers. Three couplesWendy Whelan and Jock Soto, Sofiane Sylve and Edwaard Liang, Maria Kowroski and Ask la Courdance to the first movement of Tabula Rasa; then Whelan and Soto dance as an isolated couple to Spiegel im Spiegel (Mirror in the Mirror). Wheeldon is returning to familiar ground here. His Liturgy also used music by Pärt, and, in the current edition of New York City Ballet News, he describes Whelan and Soto as his favorite partnership.

In Part I of After the Rain, the dancers wear gleaming skin-tight practice garb in subtle tones of blue and gray. The opening statement has the women facing the audience dead on as they plunge into arabesque penchée on pointe; the men partner them briefly from a supine positiona reference, perhaps, to the Agon pas de deux and the first duet in Violin Concerto. Throughout, Wheeldon emphasizes the sleekness, suppleness, and steely strength of the womens bodies, with the men seeming to root them, playing the role of solid tree trunks to their willowy branches. All the moves, incised on the vast space, are so clean and clear they might be calligraphy; they make their impact as much by means of design as through action.

Here, as usualin fact, more so than everWheeldon displays an impressive mastery of choreographic craft. Every configuration is duly intelligent and handsome. His placement of the dancers in the stage space is sometimes inventive and invariably striking. He knows how to limit his vocabulary so as to lend greater force to the elements hes selected. He makes already gorgeous dancers look like demigods fit for the glossies, thus appealing in a very contemporary way to the yearning in the spectator to identify with, aspire to, or perhaps to ownif only for a fleeting momentsomething of what our current culture recognizes as beautiful. More than any other ballet choreographer working today, Wheeldon knows how much and when. What more could anyone want? Most observers, dance critics in the lead, are so grateful for what Wheeldon can do, they dont ask for much more. Me, I find nothing moving behind the craftno hint of the deep feeling that can permeate ostensibly abstract work, no creation of an architectural universe that proposes a mysterious and absorbing world in itself. Im waiting, patiently and hopefully, to have my mind changed, but I keep remembering that, by all accounts, the genius ofto name some namesBalanchine, Ashton, Graham, Paul Taylor, Twyla Tharp, and Mark Morris, was evident from their earliest works. In the case of the last three, Ive witnessed the miracle with my own eyes.

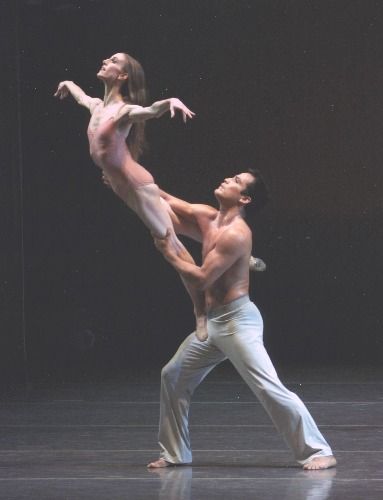

Part II of After the Rain takes us to a privatealmost sealedrealm in which Whelan and Soto reveal themselves more intimately, a state of affairs first indicated by costume. Whelan is now all pale naked flesh, but for a rose-tinted leotard; her hair falls loose to her shoulders. Soto is bare-chested, in white trousers. Both dancers are barefoota condition that, though the norm in modern dance, packs a dramatic charge in classical ballet.

As everyone talking about After the Rain seemed aware, Soto is about to retire from performing, and this, apparently, is the last role hell create. The dancing indicates the womans sense of loss and hints, as well, at Sotos grave devotionto his partners, who have much to be grateful for, and to the stage. The two body typesWhelans attenuated as a Giacometti figure; Sotos cousin to the squared-off solidity of the Aztec sculpture weve been seeing at the Guggenheimintensify the contrast suggested earlier, the mans rootedness allowing the woman to extend herself perilously into uncharted space.

All fragile grace carried to a near-grotesque extreme, Whelan repeatedly lets Soto float her into the air, where she seems as wispy as shreds of cloud wafting across a summer sky, then collapses softly, letting the energy ebb away from her infinitely pliable skeleton. (The piece forgets that Soto himself was once an airborne dancerchunky, yes, but wonderfully buoyant. Wheeldon is too young to have seen this aspect of Soto live.) A viewer susceptible to the choreography and to the evocative duet for violin and piano accompanying it, may understand the earthbound Soto figure as enabling the Whelan figure to ascend to the realm of pure spirit. Or the woman as an emanation of the mans own desire to detach himself from mundane reality as he aspires to the poetic. I must say I resisted these imaginings. Wheeldon hasnt dealt much in his ballets with deep feeling, and his skirmishes with it here are, to my mind, only sentimental. Im reminded of Jean Fritzs comment: I never cried over The Little Match Girl. I knew Hans Christian Andersen wanted me to cry but he wanted it too much.

Photo: Paul Kolnik: Wendy Whelan and Jock Soto in Christopher Wheeldons After the Rain

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

| |

Monday, January 24, 2005

MR. INTEGRITY

Peter Boal, with the New York City Ballet / New York State Theater, NYC / through February 27, 2005; April 25 - June 26, 2005

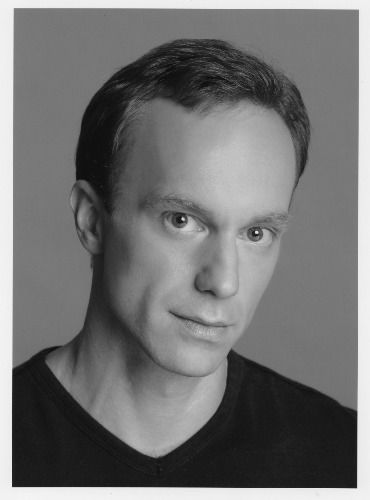

At the end of the 2005 spring season, the New York City Ballets Peter Boal will retire from the company (and its affiliate, the School of American Ballet, where he has been a leading instructor) to become Artistic Director of Seattles Pacific Northwest Ballet. The appointment is undoubtedly good for him at this stage of his career. And it will be good for the Seattle company, which, under the leadership of Kent Stowell and Francia Russell, has built a strong repertory of scrupulously mounted Balanchine works that serve as a bulwark against the corrupted taste of our times.

Meanwhile, Boals admirers are flocking to his remaining NYCB appearances, realizing that theyre unlikely to see this exceptional artist in one or another key role ever again. I saw him recently in Square Dance, illustrating two of his typical guises. Providing the most sympathetic support imaginable to his partner, Megan Fairchild, who was new to her role, he was the consummate gentleman. In the celebrated solo adagioone of Balanchines consummate creations for the male dancerhe was nobility itself, his eloquence fusing physical perfection with a suggestion of profound emotions that lie beyond words.

Boal is a rare commoditya great dancer who is not a great star. Charisma, an essential element for stardom, is not part of his makeupthough hes a disarmingly nice fellow on- and offstage. (Ive known him, slightly, since he was in the Childrens Division of SAB, the boy with the breathtaking arabesque. I did my first interview with him when he was so young, I got to meet his mother. Yearsand many reviews and several interviewslater, Id run into him in a neighborhood playground where he was caretaking his kids and I my grands.)

The glory of Boals dancing lies in the fact that it is not dependent on expressive personality. Indeed, its entirely free from self-advertisement. Self-effacing, it serves at the altar of classicism, which is based on values that are impersonal, objective, nearly abstract. Boals dancing is purity itself. The clear beauty of his techniqueevident in his earliest performances as a childis Platonic. Other impeccable technicians can seem cold or dry in performance, but not Boal. Calmly and quietly (hes the epitome of modesty and reticence), he infuses his work with human warmth and tenderness. Whats more, he displays a luminous quality that goes beyond what the body alone can convey into the domain of the spirit.

At 39, Boal has already arrived at the moment when a dancers technical prowess inevitably diminishes. Fortunately, in artists of his typethoughtful, sensitive, simple in their sincerity of purposethe soul goes on blossoming. Running a classically based company in the era of flash and trash is no easy job, but the integrity of Boals temperament may just carry him through.

Note: The New York City Ballet has scheduled a gala tribute to Peter Boal for June 5. Next week he is scheduled to appear with the NYCB in Prodigal Son on Tuesday, February 1, and Saturday, February 5 (evening), and in Apollo on Sunday, February 6 (afternoon). He will dance with his own chamber group, Peter Boal & Company, at the Joyce Theater, March 15-20, in a program emphasizing contemporary choreography.

Photo: Paul Kolnik

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

| |

Sunday, January 16, 2005

ASHES, MOSTLY

Kirov Ballet of the Maryinsky Theatre: Cinderella / Kennedy Center: Opera House, Washington, DC / January 11-16, 2005

At the behest of the Kirov Ballet, Alexei Ratmansky (now head of the Bolshoi Ballet, late of the Royal Danes) took Perraults seventeenth-century, definitive text of the fairy tale and Prokofievs haunting 1944 score and concocted a Cinderella for our cynical times. In this version of the ballet, its taken for granted that everyone in the story but the principal pair is as nasty and self-servingor simply as weirdly off-puttingas possible. The production had its premiere in St. Petersburg in 2002 and in DC at the Kennedy Center in this relatively new year several days before I got to see it, so I cant say I wasnt warned by advance description.

Ratmansky hasnt so much meddled with the basic story as given it a turn of the screw via his concept of the characters and their setting. Cinderella, infinitely sweet-tempered in trying circumstances and resilient in her endurance, is the least tampered with. If she dwells just a tad too long on embodying wonder in the face of dawning romantic love, who can blame her, her only alternative being housework? The girls stepmom is an over-the-top harridan with a certain witchy glamour, foisting not only her daughters on the eligible Prince but herself as well. The Dreadful Daughters (one skinny, one plump) are one-liner cartoons. Dad is a caricature of hapless alcoholism. (Cs dead mom makes a cameo appearance, evidence only of Ratmanskys inability to tell a story effectively.)

The Prince, mercifully, is a darling. However, his travels to find the girl whom the shoe fits consist of his visiting, first, a female cat house, then its male equivalent (both instances culminating in his being ridiculed for shoe fetishism). Ratmansky misleads you to think the excursions an investigation of the fellows sexual identity rather than proof of his ardent fixation on the worthy object of his love. The Fairy Godmother is a street person with a balabusta temperament that is almost instantaneously wearing, and the quartet of male Seasons, whom she summons to watch over Cinderella, seem to be the alter-egos of the bathhouse crew.

When and where are these creatures holding forth? The ballets set, designed by Ilia Utkin and Yevgeny Monakhov, opts for a punitively stark urban world. The locale is defined by a black-on-white drop curtain that suggests an architectural cityscape and an all-purpose structure that furnishes the stage with a skeletal, staircase-rich scaffolding reminiscent of grim elevated subway stations. The ballroom is indicated by a line drawing in radically receding perspective. Overhanging the scene, a giant metallic hoop that looks like a crown of thorns flips from vertical to horizontal, serving as both curfew clock and postmodern chandelier. A flat representation of lavishly folded red curtain, hung upstage center when the scene represents Cinderellas home, seems to be an ironic gesture in the direction of theatrical voluptuousness.

The costumes, by Elena Markovskay, run from rags to grudging riches. At home, Cinderella wears the picturesque schmates female ballet dancers affect for practice sessions. Her ball dressall limply hanging tulle of the polyester persuasion gussied up with random glittercan be described most charitably as being in the Soviet style of dress-up. The ball guests, representing take-no-prisoners chic, wear stripped-down formal dress (with rakish little black Deco period hats for the ladies). The Princes all-white evening clothes have been aptly compared by the Washington Posts Sarah Kaufman to the Good-Humor Mans uniform; I thought of Liberace (before he advanced to screaming-pink sequins). Suffice it to say that, excepting the clock-chandelier, there isnt an iota of magicor even generosity (the key to Cinderellas temperament)in the scenic investiture of this production.

As if this werent disappointing enough, the choreography is even more unequal to the occasion. It lacks amplitudein every way. Main figures in the story are left onstage for long stretches with nothing to do but perch decoratively on the scaffolding or stand forlornly, fidgeting aimlessly, trying to look concerned. Significant action for large groups has been ignored. Program-length story ballets meant for opera houses require, among other things, an ample corps de ballet deployed in sweeping, reasonably complex patterns that make a big visual impact and offset the work of the principals and soloists. The guests at the Princes partystrolling about, alternating unconvincing disco moves with flimsy indications of traditional ballroom stuffcome nowhere close to fulfilling this mission.

The action for the unattractive charactersand for the good guy and girl as well, when they have nothing better to dois dominated by angular distortions and grotesquely exaggerated mime. The dumb shows jar especially when they fail to include the props they cry out for (a scrubbing brush, for instance) or are utterly incomprehensible (what does a handful of wildly agitated fingers mean?). For comic turns, I think Ratmansky has tried to borrow from the music hall, vaudeville, and raunchy clowningbut he hasnt got any gift for the low-down genres. The antics he devises for, say, Cinderellas step-family, lack the subtle observation and timing of good clowning; devoid of depth and variety, theyre hardly funny at all.

Some of my colleagues have praised the passages of classical dancing for Cinderella and the Prince, alone and together, as consolation for the rest of the choreography, which is almost pathetically makeshift. Granted, the classical segments are prettierand charged with appealing emotions like wistful yearning, nascent joy, and, ultimately, the abandoning of self to other. That said, Ratmanskys classical mode relies on a scandalously limited vocabulary in the contemporary Russian style, showing off an almost self-congratulatory perfection of line, exaggerated liquidity of motion, circus-worthy flexibility, and the ability to spin like the proverbial top. It favors the eye-catching stuff while blithely ignoring smaller, more intricate pleasures, like petit allegro. Worse still, these passages lack a coherent structure. They consist of one gorgeous-looking move after another, performed in disjointed succession rather than in musical phrases. Unrelated to one another as these bits and pieces are, its impossible for them to add up to anything. Hierarchy, modulation, luciditykeystones of classical danceare noticeably absent here.

The single area in which Ratmansky succeeds in his Cinderella is the psychology of romantic love. His solos for his heroine and his duets for her and her prince are both inviting and persuasive. Cinderellas feelingsas she is gradually introduced into a world that includes loveare given the leisure to shift and to register, in observant detail. The duets display not just the ecstasy of love triumphant but also the process of developing love and its necessary companion, trustalong with the pitfalls of momentarily failing self-confidence, missed connections, and even misunderstanding. If the happy ending of the ballet seems barely possible in the vile surroundnot just of Cinderellas dysfunctional family unit but in the ostensible aristocratic world as wellthat Ratmansky creates with such relish, perhaps that snatched-from-hell miracle suits our corrupted times.

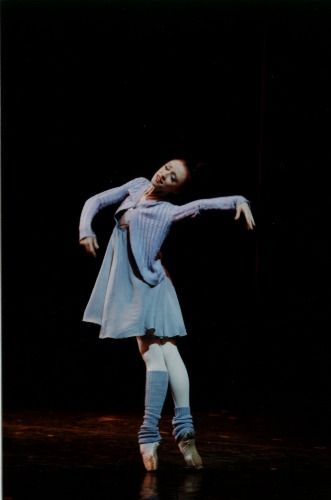

The two sets of principals I sawNatalia Sologub with Igor Kolb and Irina Golub with Andrei Merkurievwere marvelous within the limited range the choreography offered them. Sologub, rightly chosen for the first cast, made the more poignant of the Cinderellas. A lyrical dancer with an infinitely malleable body, she created a heroine modest and innocent in demeanor, tremulous in her anticipation of joy. She was all pathos, vulnerability, and tenderness, spiced with just the right amount of spunk. When, at the ballets close, she lay down in darkness with her beloved, sheltered only by a velvety night sky adorned with drifting clouds and glowing stars, she seemed to have found her proper domainin the realm of kind hearts, not coronets. Irina Golub was more theatrically vivid in the role, more firmly planted in her technical prowess and in her determination to show it off, along with her considerable charms. If her interpretation seemed to me to lack the quality we call soul, it was because shes less naturally suited to Cinderellas wistful yearning and reticence, to that heroines embodiment of unalloyed goodnessand because Id seen Sologub.

Both Kolb and Merkuriev, both of modest height but great talent, made wonderful, very different, Princes. Kolbs dancing is strong, clear, pure to the point where it might provide textbook illustration, and yet informed with grace. He does a dutiful job of creating a character, but you can tell that his real raison dêtre is to display the abstract beauty of classical dancing, step by step. Merkuriev is immensely appealing in looks and mannerthe kind of guy a girls mother hoped shed bring home back in the days when suitors had to earn parental approval. Hes warm, sweet, and boyish, impeccable yet easy in his behavior. Though hes a fine technician, he keeps his dancing uniformly soft. All the edges are deliberately smudged, which gives his work the voluptuous quality of daring deeds half veiled by fog. All four of these dancers deserve more challenging material, and their already admiring followers deserve to see them in it.

Ratmanskys mind seems to be a grab-bag of references, packed with things like Russian folk dance, to say nothing of all the ballets he has ever seen. My favorite throwback in his Cinderella is the resemblanceextending even to a couple of direct quotationsof the heroine and the Stepmother anti-heroine to the pure, deserving, gentle-tempered Hilda and Birthe, the hot-tempered, lascivious daughter of trolls, in Bournonvilles A Folk Tale.

A pair of useful questions to ask about any production of Cinderella: One, would you take a child to it? Two, would you take a grown-up to it? For me, Frederick Ashtons ravishing version, created in 1948 for the Sadlers Wells (now Royal) Ballet and shown to just about universal delight in New York last summer as part of the Royals contribution to the Lincoln Center Festivals Ashton Celebration, gets a pair of yeses; Ratmanskys gets two noes. And yet, without any doubt, Im curious to see Ratmanskys next effort myself.

Photo: Natasha Razina: Natalia Sologub in the title role of Alexei Ratmanskys Cinderella

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

| |

Sunday, January 9, 2005

GOING TO THE WOOD

Savion Glover: Classical Savion / Joyce Theater / January 4-23 2005

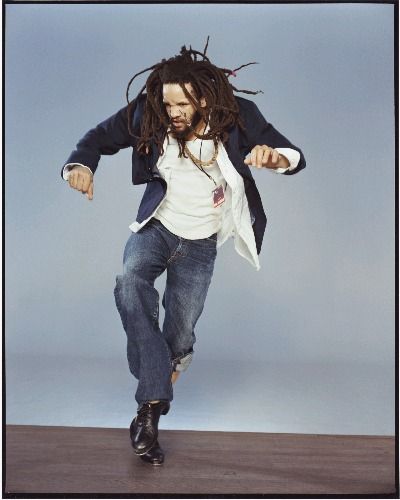

Savion Glover is more than the greatest tap dancer of his generation. Hes a phenomenonas a technician, an inventor, and a compelling presence. Hes been going from strength to strength since he was, at twelve, the tap dance kid. His latest project, Classical Savion, has him strutting his stuff to music by Vivaldi, Bach, Bartók, and Mendelssohn, with Astor Piazzolla thrown in for seasoning. Then, just in case you were missing taps more conventional accompaniment, Glover offers that as a finale, integrating the classical musiciansyoung, enthusiastic academy virtuosi led by Robert Sadininto the suave proceedings of his familiar partners, The Otherz, a handful of jazzmen who couldnt be more mellow.

The stage provides Glover with a wide, miked wooden platform, the musicians ranged in curving tiers behind it, as if to hold the dancer in their embrace. Looking a decade younger than his 31 years, Glover enters wearing formal black evening jacket and trousers with a cantaloupe colored shirt (untucked, unbuttoned at the neck and cuffs) and a black bow tie (untied). The costume suggests a rebellious guy whos fully aware of the grown-up dress code for concert performance and complies, all the while adamantly reasserting his own identity. His luxurious dreads are caught up in a low pony tail; he sports a beard that makes you think Abraham Lincoln.

In the course of what may be the longest vigorous solo stint in Western dance history, hell shed the jacket so that you can watch the shirt darken as it soaks up his sweat. In the course of the show, hell change the shirt a couple of times to a fresh one of a different hue, leaving the subsequent shirts open to reveal a white singlet, adding a bead necklaceall this a gradual return to the image of a slouchy street kid. Eventually he dances clutching his water bottle in one hand and, in the other, the black hand towel with which he mops his face. In the wake of his movement, the towel flares like a quietly menacing flag.

Like his costume, his stage demeanor slowly and inexorably reverts to a state that seems natural to his identity. Glover used to be a glum, deeply introverted performer. His refusal to make eye contact with his audience looked, to viewers expecting an ingratiating entertainer, both neurotic and hostile. Hes lightened up some in the last couple of years. Hes learned to smile, and his smile is delicious if still somewhat surreptitious. A quarter of the way through the program, though, he begins to lose his apparent resolve to look his public in the face. Performing to an excerpt from Bachs Brandenburg concerti, he dances largely with his back to the audience, as if he were directing his efforts to the harpsichordist positioned upstage, or in profile, eyes averted from the house. Maybe its time, Im thinking, to quit asking him for something different. The fierce inward focus of his dancing suggests that hes delving deep into himself to reach something beyond himself, and its not our love hes after but the achievement of ecstasy. Let him be; after all, he does take us along with him.

Now for what really countsthe dancing. Heres what I notice most: energy (which seems to be part physical, part passion); control (tap is, among other things, a balancing act); a rhythmic acuity operating at genius level; a sly wit. Glover can, and often does, make a big ferocious sound, savage and blunt, the noise of a bad boy in the throes of a singularly destructive tantrum. At other loud moments he becomes a one-man artillery attack, all lethal precision. He juxtaposes his Orange Alert work with cascades of slow lustrous tapping (sensuousness in the abstract) or a tiny, quiet babble of taps that might come from small animals or even insects busily at work on a spring morning. Sometimes he rides the music; sometimes he becomes one of the instruments in the ensemble; sometimes he converts the score into a concerto in which he alternately plays solo and blends back seamlessly into the group.

Hes his own choreographer, of course, and his invention is wide-ranging and seemingly inexhaustible. I cant count the number of things I hear (and see) Glovers feet accomplish that Ive never been privy to before. The improvisatory air of everything he does is invigorating, and the conversation his feet conduct with the floor is probably the most fascinating dialogue Ill hear all year.

About the music: People have said even about works like Balanchines sublime Concerto Barocco, Why would anyone add dance to music that is evidently complete in itself? Glover has gone even further in annexing classical scores, not merely adding a visual dimension to an auditory one as ballet does, but adding a contrasting and possibility competing sound. And not in the gentlemanly fashion of Paul Draper, but in the style of a tough contender. Myself, I think its an interesting experiment, one worth continuingto see how the odd coupling can be refined.

Meanwhile, Glover seems to have some notions about a rapprochement between classical and jazz music. In the closing segment of Classical Savion, he introduces the classical instrumentalists by name, one by one, and has each of them execute a bizarre little riff, as if to show that a musician from this camp can be a virtuoso and with-it at the same time. Then he summons the jazz band for the same exercise, lets it jam for a bit (lovely!), with the classical gang eventually invited to join in. Glover, feet still working, but only mildly, ends up center stage, facing the full ensemble, in the position of conductor. Admittedly, these goings on are disarming, but, apart from the jazz combos playing, they arent absolutely necessary.

My only other reservation about the program is that, except for a few phrases, it offers no opportunity to hear Glover dancing without music. Given the nature of tap, it can be accompanied perfectly by silence. But this is the most minor complaint, just a critics tic. In truth, Im down-on-my-knees grateful for Glovers dancingin any fashion he chooses. Dancing like this is simply as good as it gets, and I consider myself wildly fortunate to be sharing time and place with such an artist.

Photo: Len Irish: Pre-classical Savion.

© 2005 Tobi Tobias

| |

|