main: June 2006 Archives

Postclassic Radio has been languishing lately, which I regret. But I've just put up a couple of major piano works. One is Ralph Shapey's Fromm Variations, played by Robert Black. Because Shapey landed a position at the University of Chicago, and deeply wanted to be in that orchestra-circuit crowd, he got a reputation as one of the academics, which I consider unfair. Never graduating from college, Shapey taught violin lessons for a living the first half of his career, and hung out in Manhattan with the same abstract expressionist painters as Feldman (one of whom, Vera Klement, he even married). Within his granitic atonal language is a wonderfully sustained sense of imagery, forms that hover in space somewhat like Feldman's, only thornier. I'm admittedly not crazy about Shapey's vocal music - he wrote a lot, and his vocal writing is pretty ungrateful - but his instrumental music can be taut, powerful, and yet somehow almost meditative. The Fromm Variations is his finest keyboard work, and soon I'll treat you to the Seventh String Quartet as well.

Also up is Fog by pianist composer Jessica Krash, a piano dream in which memes from music history bump into each other - including a major third that keeps trying to turn into Schoenberg's Op. 19, and never does. It's been awhile since I've discovered a new composer so far out of left field as the aptly-named Krash. Plus, Swiss toy-pianist Iris Gerber has been bringing some new repertoire for that instrument to light. I'm uploading Maria De Alvear's All music is a mandala (2002) and BBAE-Diagonal für Toypiano und Zuspielband nach Composition 2215 by Daniel Ritter.

As to why such a huge proportion of postclassical music is for piano or other keyboard - I've pondered this question for a long time. I know why I've written so many piano works, which is largely because my music has mostly been championed by pianists - I've failed to interest clarinetists and bassoonists, for instance, in solo works I've written for those instruments. A certain breed of pianists seems genuinely ravenous for new repertoire. I try to keep plenty of variety, but I could easily let Postclassic Radio devolve into an all-piano-music station.

If you've e-mailed me recently and haven't heard back, please be patient. I've had a few family things occupy me lately, and I am more than a month behind in my e-mail correspondence, absolutely inundated with legitimate messages that I'd like and need to answer (including three from bankers in Nigeria who are going to make my fortune, mark my word). If I did nothing else between now and September but answer them, I'd never get to them all, so some will undoubtedly fall through the cracks. Feel free to send a repeat message. Let me know if you're independently wealthy yet seized by a desire to be a composer's secretary.

UPDATE: A friend writes to commisserate, and brings up a good question: Why do so many people send us requests for information that they could easily find in reference works, or else by Googling? I'm always getting queries about Nancarrow, La Monte Young, tuning, and other subjects, some of which are already answered on my web site, in my books, or other easily accessed sites - and La Monte Young is still around to answer his own questions! I've even had high school students, assigned to write reports, write me for general info about American music. I'm glad to answer such questions when they require a specialist, but I do wish people would do a little research on their own, and not assume I'm sitting around with nothing better to do.

The Mailman anecdote reminds me of another early disappointing encounter with celebrity. The first time I ever had a famous visiting composer look at my music, I was a freshman at Oberlin, and Lukas Foss was the composer. I had written a song for soprano, flute, and piano on a poem by Jean Valentine. It wasn't good - if I thought there were any risk of it being resurrected after my death I would burn the ms., but there is no cause for such apprehension - but it was seven or eight minutes long and rather elaborate, dissonant, effect-seeking, and as avant-garde as my 18-year-old sensibility could muster, probably most under the influence of Berio's Circles. In the last section I attempted a negative climax by suddenly isolating the soprano in a line dotted only by occasional single-note shrieks from the flute. This tendency to close a piece anticlimactically by making it suddenly turn quiet and sparse has been lifelong with me, employed as recently as last March.

In came Maestro Foss. The German accent with which he had stepped off the boat in 1937 at age 15 had shed little of its Schichtdicke by 1973, giving him an air of Old World authority. He had just authored Elytres and Paradigm, and, from the reverent way he pronounced their titles, seemed proud of them. I got in line, and when my turn arrived, he went slowly through my score, as my circle of peers looked on. When he came to the dramatic final page, with the soprano suddenly abandoned to a silence cut only by despairing blasts from the flute, he said:

"It looks like you got tired of vorking on ze piece, and just finished it very quickly."

Nothing in my experience had prepared me to argue with Great Men, just as nothing in my character predisposed me to accept their judgment. I had never heard the term "negative climax," and didn't have it handy to use in self-justification. I had never verbalized, even to myself, my instinct that that was an effectively counterintuitive way to end a piece. It seemed obvious to me that abruptly robbing a soloist of her contrapuntal support was a dramatic gesture, and one that I was undoubtedly not the first to have thought of, but I had no words in which to advance this theory that would outweigh his frank dismissal. Least of all had I been raised impolitely enough to utter the one sentence that my besieged brain managed to string together: "Geez, for a Famous Guy, you're sure not very insightful." So, by reflex, I silently nodded.

Ever since that day I have been dubious of hit-and-run assessments by Great Men, even when I myself am the great man. A composer recently asked to have a lesson with me, and I replied that, while I am always happy to look at someone's music, "a lesson" is something I feel capable of giving only the fourth or fifth time I see a student, after I've gotten an idea what they're trying to achieve in piece after piece, and have had a chance to observe what is holding them back or subverting their intentions. The inept feature that sticks out and ruins a young composer's otherwise suave piece might be the only original thing in it; it may be that they should keep the flaw and lose all the suavity they learned from other people's music, but it would take some depth of observation before I'd chance recommending that. I am no fan of the "professionalizing" type of composition teaching that tries to make a student's music conform in notational style and sound to some reputed common standard. To become a "professional composer" is one thing, to become an artist almost the opposite. The type of teaching I believe in is more like therapy, untangling the person's misassumptions and motivations and trying to clarify what appeals to them musically. I almost never write notes into a student's score, and I live by a saying of Blake: "If the fool would persist in his folly, he would become wise." It's a long process, and the times I've felt like I was really able to help a student, it's usually been over a period of a couple of years, and was a rewardingly intense (and mutually beneficial) encounter.

There have been a few times I've been "Great Manned" and enlisted to visit a school and comment on student compositions. I do it with the understanding that it's a kind of game, and that one of the ground rules is, if a student gets an urge to tell me, "Geez, for a semi-famous guy, you're not very insightful," I'll be happy to nod in agreement.

UPDATE: By the way, I don't mean to imply that there's no point in bringing composers in to look at student works. On the contrary, it's tremendously valuable - for the composer. Looking through student works gives me new ideas and grist for my writing mill, while showing me which way the winds are blowing. But I think the best the student can hope for is that I'll say something so boneheadedly mistaken that he'll enjoy recounting the story 30 years later, as I did this.

A friend sent me this old 1960s photo of five composers. If you can identify half of them, you're more of a 20th-century music wiz than I am:

Give up? Recognize any of them?

They are, from left to right, William Duckworth, Paul Creston, Sydney Hodkinson, Iain Hamilton, and Martin Mailman. Duckworth is the close friend who had the photo. Creston's music I've never gotten excited about, but I've always been curious because he was one of the few composers, along with Schoenberg, Ives, and Ruggles, that Henry Cowell championed with lengthy analytical articles. Mailman was Duckworth's composition teacher, and later the local composing celebrity around Dallas, where I grew up, as long-time composition professor at North Texas State U. I remember in high school my composition teacher, the band director Howard Dunn, bringing in Mailman with great reverence, as the star composer of north Texas. The only incident I remember is that Mailman chewed out a fellow student of mine for beginning Beethoven's "Waldstein" Sonata on the piano and playing it softly, when the dynamic marking, Mailman assured us, was ff.

Of course, the actual dynamic marking is pp. Little surprise that Mailman, who died in 2000, is forgotten today except in the symphonic band arena, but he was someone who, as Southern composers, Bill and I got to experience in common. The student who earned his disdain by playing Beethoven at the correct dynamic was Robert Hunt, still a friend and a superb musician, and, last I heard, conductor of the Midland-Odessa Symphony Orchestra in west Texas.

Via The Rambler via Alex Ross (and sired by Seattle Slew), here's the video of the BBC Symphony Orchestra playing Cage's 4'33" at the Barbican in 2004. For inscrutable reasons that I imagine would have perplexed Cage, the audience suppresses their coughing until between movements (I mean, they don't often hold back much during normal symphonic works, now, do they?). Swelled to such proportions, the piece really does become an enormous joke, but one that the polite British seem eager to appreciate.

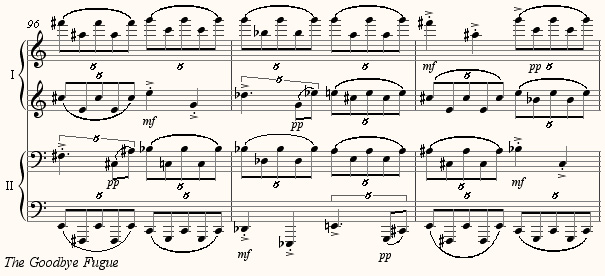

I'm writing a piece for piano four hands. The first four movements are already 25 minutes, and I'm adding at least one more. They're sort of sketches for pieces I've been wanting to try, and because they're not particularly related, I'm using the generic title A Book of Music. It's for a couple of students who have a piano duo, but it's also a project I've wanted to work on for more than a decade. I've always had a soft spot for two-piano, or four-hand, works, and it's rather remarkable the number of such works that are either my favorite, or near-favorite, work by that composer:

Ligeti's Monument - Selbst-Portrait - Bewegung

B.A. Zimmermann's Monologe

Stockhausen's Mantra (my favorite pieces by all three composers)

Busoni's Fantasia Contrappuntistica

Satie's Trois morceau en forme de poire

Wallingford Riegger's Variations Opus 54

Kevin Volans's Cicada

Tenney's Chromatic Canon

Bach's The Art of Fugue

Years ago I wrote a two-piano piece, I'itoi Variations, which was a huge, ambitious, take-no-prisoners monument of tremendous ensemble difficulty, not the sort of thing that two pianists can sit down and breeze through in an odd moment. Since then I've always wanted to write something more approachable, closer in spirit to Trois morceau en forme de poire. It's a great medium. It shares with solo piano music that you can set tone color aside for the moment, yet it also frees one from the limitations of ten fingers, and opens up the entire range of the instrument for simultaneous use. No wonder it's the chosen medium to substitute for the orchestra in a thousand transcriptions.

My students will premiere A Book of Music this fall, and then I'll make it generally available. It's refreshing to write a little gebrauchsmusik, thinking at least as much about the enjoyment of the performers as that of the audience. I love playing four-hand music myself, and one of the best things about it is that it offers such opportunities for seduction. What better association for musicians to have with my melodies than that they were prelude to an evening of unexpected passion?

UPDATE: That working title was too dull to impose on a piece I've come to like as much as this one. The new title is Implausible Premises.

I was once told, on the good authority of someone who played his music, that there were no extant photographs of the reclusive Italian composer Giacinto Scelsi - he didn't like having his picture taken. I printed this factoid in the Village Voice, and in response someone sent me an indistinct photo of an old man in a wool cap, which the sender claimed was the only known photo of Giacinto Scelsi. Now, courtesy of Chicago critic Marc Geelhoed, whose name has graced these pages before, I find a photo of a young, dapper Giacinto Scelsi.

I was once told, on the good authority of someone who played his music, that there were no extant photographs of the reclusive Italian composer Giacinto Scelsi - he didn't like having his picture taken. I printed this factoid in the Village Voice, and in response someone sent me an indistinct photo of an old man in a wool cap, which the sender claimed was the only known photo of Giacinto Scelsi. Now, courtesy of Chicago critic Marc Geelhoed, whose name has graced these pages before, I find a photo of a young, dapper Giacinto Scelsi.

Please send me all remaining photos of Giacinto Scelsi c/o Arts Journal, and I'll print the best twenty.

Frank Oteri has asked for my reaction to an article by artist/critic Matthew Collings about the experience of being an artist/critic. It starts out, "For a long time I've led a double life. I've been an art critic and an artist." Well, the experience he describes isn't mine. I get a little pissed off when people describe me as "wearing two hats." Literally as well as figuratively, I only wear one. "Kyle Gann" is a construction of musical and other experiences reaching back into the 1950s, and those experiences condition every article he writes as well as every piece he composes. I don't draw on one set as a reviewer and a different set as a composer, and I have never had the experience of moving from composition to reviewing, or vice versa, and feeling, "OK, now I'm a different person, or have a different point of view." To keep these functions separate would emasculate both. My life as a reviewer has had a salutary effect on my music, and I've always felt that my writing started to suffer when I wasn't composing enough. Of course, the composer KG rarely composes according to the directions of the critic KG, but that's because one is the function of the subconscious and the other of the conscious - and I'm as much at the mercy of my muse as anyone. In fact, I've even written reviews that ran away with me and seemed scary-crazy when I wrote them; I'd screen my phone calls the day they appeared in print, but these are invariably the ones I got the most praise for. I do hope that after I slough off this mortal coil my work gets considered, if at all, as a unity, even if one containing contradictions. The keys to my music are in my writing, and vice versa.

So is there anything I can add to this dialogue besides, "Baloney!"? Well, there is a critical function which, in many young composers, sets in too quickly and makes composing difficult. With half my composition students I have to tell them to turn off the critical voice in their heads long enough to get enough notes down, to see how the piece is growing before you start chopping it up evaluatively. I was particularly susceptible to this as a young man, with an aggressive superego that would damn anything I did before it could get off the ground. Perhaps that had something to do with my penchant for criticizing. But the balance between taking creative chances and self-criticism is one that every creative artist has to work out for himself, regardless of his day job. Right now there's nothing I want to do more than quit being a critic - not at all because I think writing criticism detracts from my composing, but because people treating me as a critic quite definitely detracts from their treating me as a composer. I can handle the contradiction just fine. It's others who can't.

UPDATE: On reflection, I'm not sure this disagrees with the original article, because I can't tell for sure what the point of the original article was. I was asked to respond, and these sentences flew to mind.

Alex Ross, who has a nice article on Morton Feldman in this week's New Yorker, quotes, on on his blog, the late György Ligeti on his view of music history:

"Now there is no taboo; everything is allowed. But one cannot simply go back to tonality, it's not the way. We must find a way of neither going back nor continuing the avant-garde. I am in a prison: one wall is the avant-garde, the other wall is the past, and I want to escape."

I agree completely. But escaping from a room with only two walls has never struck me as particularly difficult.

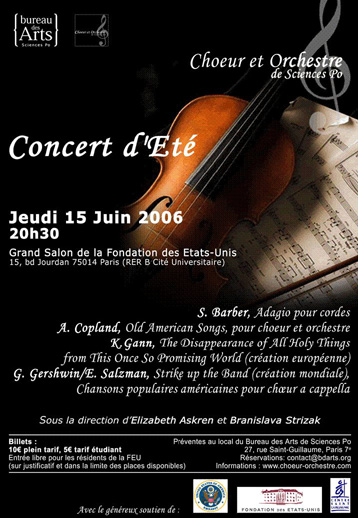

According to the Guinness Book of World Records, the longest song title ever was that of Hoagy Carmichael's 1945 ditty, "I'm a Cranky Old Yank in a Clanky Old Tank on the Streets of Yokohama with my Honolulu Mama Doin' Those Beat-o, Beat-o Flat-On-My-Seat-o, Hirohito Blues." I think I may possibly hold the record for the longest title of an orchestra piece: The Disappearance of All Holy Things from this Once So Promising World. Like several of my titles, it's a line from a poem by the great underrated poet Kenneth Patchen. The piece is being played next Thursday, June 15, in Paris, conducted by Elizabeth Askren on a program of American music:

It's the work's first performance since the premieres by the Woodstock Orchestra in 1998. I, alas, won't be there. But I'm having such a blast making microtonal orchestras with Li'l Miss Scale Oven and Kontakt 2.1 that it would take more than a mere Continental premiere to crowbar me away from my computers.

UPDATE: Art Jarvinen says he has a chamber orchestra piece with a longer title: Mass Death Of A School Of Small Herring (The Natural History Of Deductible Rooms). Personally, I think having a subtitle in parens is cheating.

I just finished reading, and immensely enjoyed, A Talent for Trouble, the biography of film director William Wyler, by my fellow Arts Journal blogger Jan Herman. Two things at the end of the book struck me.

One was Wyler's feeling about color photography, which he was late to switch to. "A red chair doesn't look unusual in reality," he once said, "but on the screen, you can't take your eyes from it. That's because the frame itself is not natural. It's delimited by the blackness surrounding it. We don't actually see that way with our natural field of vision. I was late in using color partly because I felt color could be phony, exaggerated." More evidence of what I'm always saying, that art is about appearances, not reality. A lot of young composers, I think, as well as older ones, make bad music because they're focussed on what the music really is, not on the way it appears to the audience.

The other point of interest was an encounter with Alfred Hitchcock. Wyler made all kinds of films: westerns (The Westerner, The Big Country), comedies (Roman Holiday), war films (Mrs. Miniver, Memphis Belle), social commentary (The Best Years of Our Lives, Dodsworth), suspense films (The Letter, The Collector), a musical (Funny Girl). One of Jan's themes throughout the book is that this versatility worked against Wyler's reputation, since in the '60s an auteur theory arose that (over-) valued each director's idiosyncratic viewpoint, and demanded that he turn out films exploring the same themes over and over. Hitchcock, "master of suspense," benefitted from this, but Wyler called him "a prisoner of the medium." Once Hitchcock admitted to Wyler that he was jealous: "You can do any kind of film you want. I can't. They won't let me." (Watch Hitchcock's late comedy The Trouble with Harry, and you might conclude that it was a good thing they didn't let him.)

Auteur theory is a big subject in film criticism, but its musical counterpart, though quite patent, is hardly discussed. Many of the most well-regarded recent composers are those who evolved an immediately recognizable trademark in their music: Feldman, Reich, Scelsi, John Adams, Meredith Monk, Charlemagne Palestine, Branca, and most of all Phil Glass, who has taken recognizability to an extreme that has ruined him for more sophisticated circles. Interestingly enough, this seems more true of the famous Downtown composers than of the Pulitzer crowd - it's difficult to imagine reliably recognizing a work by Corigliano, Zwilich, Harbison, or those guys in ten seconds of a drop-the-needle test. (Babbitt's an interesting case - uniformity not necessarily leading to recognizability.) I suspect that this partly accounts for Europe's preference of Downtown Americans over Uptown ones, since Europe is where auteur theory originated and flourished. They seem to like our composers who carve out their own distinctive groove.

This is a personal issue for me, because, creatively, I find myself much in sympathy with Wyler. I too write static minimalist pieces (Long Night, The Day Revisited), wild collages (Petty Larceny, Scenario), microtonal pieces (Triskadekaphonia, How Miraculous Things Happen), jazz harmony pieces (Bud Ran Back Out, Private Dances), atonal pieces (The Waiting, I'itoi Variations), grand pieces for chorus and orchestra (Transcendental Sonnets). (I'm not the only Downtowner in this boat; Jim Tenney and Larry Polansky have similarly kaleidoscopic outputs.) Inside my head, my musical reflexes are so fixed and repetitive that I feel like I keep writing the same work over and over again, but I have trouble believing that my music comes off that way to the listener, and I sense that people have trouble figuring out what my central style is. I have a repertoire of melodic tendencies that I've nurtured closely for 30 years, and a few rhythms that have become absolutely fetishistic, but they recur disguised by widely ranging contexts. In that respect I'm really a little like Nancarrow, who used the same melodic and rhythmic tics in every piece, but whose music - if you brush aside the fact that it's almost all for the same instrument - runs the entire gamut from meticulous discipline to improvisatory abandon, and from modernist abstraction to boogie-woogie.

Since I so admire so many of the auteur-type composers, I had always intended to gravitate toward a small set of ideas and explore them over and over, as my friends John Luther Adams and Peter Garland have. If nothing else, it strikes me, in the current climate, as a good career move. But my muse doesn't take directions very well, and it just works out that after writing a motionless Zen essay I'll next get inspired to write a chaotic parody, and then a postminimalist dance. Jan discounts the claims of the auteuristes and praises Wyler's versatile ability to adapt to each new genre. It's in my own best self-interest to ride in that bandwagon myself.

Some months back Felix Meyer and Heidy Zimmermann asked me to write an article on Edgard Varèse's impact on American music for a book that the Paul Sacher Foundation would publish. Well, the book - Edgard Varèse: Composer, Sound Sculptor, Visionary - is out, and rather than being the modest monograph I had envisioned, it is mammoth: a 500-plus-page coffee table compendium loaded with photos, diagrams, and manuscript facsimiles. Thirty-two authors are represented, and the articles cover Varèse's student days, politics, patrons, personality, opinions of jazz, friends, influences, and other facets of this hard-edged figure.

Dipping into it at random (and I'm too immersed in composing to do more at the moment), I find some stunning quotes in Ulrich Mosch's article about Varèse's influence on Wolfgang Rihm: "Varèse [this is Rihm speaking] might have become much more of a key figure if he had only stood up more forcefully for his subjectivism and offset his image of the composer as objective architect with a different image: the artist as 'manic-compulsive.' As it is, we have to dig a long time before we reach him." According to Mosch, Rihm feels that Varèse took on a self-protective cover of rationalism that was good politics for his milieu, but counter to his most basic compositional instincts. And he quotes something Varèse finally argued to Alan Rich in 1965: "Composition according to system is the admission of impotence."

Whew! Well, the 20th century certainly needed a champion of subjectivity from the progressive side, someone to counter the then-spreading prejudice that subjectivity was the fetish of philistines. For my own article (and I hadn't previously given Varèse much thought in 20 years), I found that that subjectivism made him forever suspect among the academics, who otherwise were delighted by his counterintuitive structures and extreme detail of notation. Meanwhile, the Downtowners loved him for his embrace of noise and that very subjectivism, though they resented his role in the imposition of a fanatical approach to notational exactitude. Exciting and original but thorny and personally off-putting, Varèse was a difficult figure to integrate into our musical landscape. This book looks like the most heroic attempt ever.