A journal of our visit to Sans Souci and notes on a program of the Four Nations Ensemble in New York City on March 7th, 2002

A day at Sans Souci, Frederick the Great’s favorite home, is immersion in a Rococo world. The gardens cascading below the pavilion (it is neither a palace nor chateau but a Prussian Trianon) are as visually complex as the interior walls are energetic with silver and gold traceries and shell work. The Four Nations Ensemble’s concert (March 7th in New York City) is a program of sonatas from Sans Souci written to fill the music room central to life at Frederick the Great’s favorite home. There, a select group of heady friends could commune in a German dwelling for the muses, a Helicon.

This King was a francophile (his collection of Watteau is a revelation and he felt the German language “crude and almost barbaric”), an industrious flautist-composer, and a rococo obsessed art patron. At his death, his nephews and nieces simply closed the doors on his encrusted rooms and decorated their palace apartments in solid wood triangle, parallelograms and quadrangle forms. Moving from a Frederick wing of a palace to a Fredrick Wilhelm II wing is shocking in disagreement. There is no modulation from one generation to another, only a well marked boundary

Marie Antoinette preferred afternoons with sheep and bagpipes in an imitation peasant village at Versailles but Frederick’s whim was to import Voltaire and employ C. P. E Bach along with the other fine composers of mid 18th century Germany for his edification and pleasure. Pleasures that charm the sense and captivate the mind!

Rococo music is reputed as being fussy, pretty, superficial, decorative, and inconsequential. But listen to what Frederick writes in a letter to his sister about some music he has written for her. “In the adagio I was thinking of the long months since our parting and therefore found the tone of painful lamentation. In the allegro I indulged my hope for seeing you again.” These are the words of a young romantic and not the fashion obsessed aristocrat. They also represent a series of musical values that belie the reputation of music at Sans Souci. In fact, it is at Sans Souci where the Empfindsamer, or sensitive stile enjoyed its greatest flowering.

Four Nations has performed important rococo masterpieces from the sensual and voluptuous sonatas of Francoeur to the beguiling, sparkling complexities of Locatelli’s trios. However, from the first notes of Franz Benda’s F minor sonata for violin and continuo we realized that our concept of rococo music would need to expand. This music is almost uncomfortable in its search. The florid ornamentation, though demanding great virtuosity, does not amuse or astound but acts as a destabilizing element in these three movements. This is not “pretty.” It is expressive. Dark and compelling, it lives outside the world of courtly tastes and manners.

Franz Benda (1709-1786) is known as the father of the German violin school and 33 of his sonatas are found in an important manuscript for all performers and amateurs of late Baroque music. The music explores many aspects of contemporary style and violin technique. It present a panorama of German musical thinking of the mid 18th century. But as an anthology it demonstrate the art of variation, of improvised, rococo ornament. Each movement presents the violin part in two and sometimes three versions. Richly ornamented and then more richly ornamented, this is a “how to” for elaborating a melodic line. Other composers have given us similar examples of their elaborations; Corelli, Tartini, Nardini, even Bach. Like his colleagues Benda ornaments slow movements but unlike his contemporary’s scores, we have here written out elaborations for Allegros and Prestos! There is imagination in these sonatas that challenges and rewards the violinist who chooses to tackle them.

Frederick’s love of thought and art is remarkable among monarchs. However, Frederick had limitations and though he was surrounded by Bachs, he never quite understood the towering quality of either J. S. or his son, C. P. E. Bach. Though no one’s music from Berlin speaks more vibrantly than Carl Phillip’s, it seems that he was kept in the shadows throughout his career in Berlin. Johann Sebastian’s visit, though a curiosity for the King, was not fully recognized as the event of the century at Sans Souci. The arrival of the dedicated score for The Musical Offering went unnoticed. In a perverse manner, we will skip over C. P. E. Bach to look at a lesser-known keyboard player in Frederick’s service, Christoph Schaffroth (1709-1763). (2014 is the tercentenary of Carl Phillips’ birth and we plan to celebrate.)

Schaffroth was part of Frederick’s earliest musical establishment and seems to have been unaffected by empfindsamkeit music. His sonatas are beautifully composed in an Italian gallant mode. They are structurally simple. We do however need to ask ourselves to what extent these simple lines should be elaborated with ornaments in Benda’s fashion. Should the bass lines of repeated notes be varied as C. P. E. Bach urges?

Of all the works on our program, Johann Gottlieb Graun’s Trio in G for flute, violin and continuo meets our expectations for the delight and vitality we have come to expect from rococo music. Johann Graun (1703-1771), student of Tartini, teacher of Wilhelm Friedemann Bach, and admired by Johann Sebastian Bach has left unexplored chamber music delights and this work will make you want to know more. How fine that he gives the cellist rococo riffs that respond to the flute and violin. Here there is lyricism and sparkle that reminds us of the silver and gold that shimmers by candlelight or sunlight in every room at Sans Souci. And yet, all the embellished charm is supported by excellent counterpoint. No wonder Johann Sebastian sent his favorite son for lessons with this modern master.

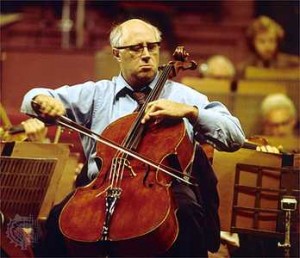

There is one important instance in which Frederick opted towards “tomorrow” rather than “yesterday”. He was committed to the education of his nephews knowing that Frederick Wilhelm would be king. A series of letters between Frederick and Antoine Forqueray, the Parisian viola da gambist, chart arguments for teaching the prince to play a noble viol rather than the vulgar cello. The arguments are beautifully drawn by the French virtuoso but to no avail. In 1773 the King sent for one of the two Duport brothers, both cellists. Jean-Pierre Duport (1741-1818) joined the king’s orchestra and gave lessons to the future Frederick Wilhelm II. This was a fruitful decision. Beethoven wrote his opus 5 cello sonatas for performance with Duport in Berlin. Frederick Wilhelm’s abilities and love of the instrument inspired Mozart and Haydn to write quartets that place the instrument a leading role and are now part of the core chamber music repertory. Duport’s own sonatas are lyrical, operatic, often dramatic and stormy works written with the architectural clarity of early Classical music.

If Frederick had no particular interest in “yesterday’s” music of Johann Sebastian Bach, the great master held the accepted style in Potsdam in questionable esteem. He labeled this music “Prussian Blue.” Prussian Blue is a dye that appears rich but when subjected to sunlight (scrutiny?) fades quickly. What a razor sharp insult worthy of Jane Austen! Even so, Bach takes his compositional brush and adorns already baroque melodies in rococo decoration. He does this remarkably in his flute music. Bach, to his expense during his lifetime, loved to fuse any two or three stylistic characteristics that appealed to him. He lays Italian ornaments on a French sarabande. He can fuse the Vivaldi concerto form with that of a Da Capo aria. And he can mate a ritornello virtuoso concerto with a German fugue. The response from his contemporaries was often an irritated, “What is THAT?”

And so, with his monumental B minor sonata for flute and harpsichord as well as this more domestic work in E major for flute and continuo, Bach has gone Empfindsamkeit and written what he feels is a modern chamber piece. The E major sonata was probably written for one of Frederick’s court flautists. But beyond anything else that was heard in this royal music room and in the words of John Dryden, it is music charms the sense and captivates the mind.

Dear Andy, I’ve just read your most enchanting program notes for your Wednesday concert, and it pains me deeply that I am unable to hear it in person. Wishing you a huge audience and equally huge success, I dare to hope that the program will be recorded.

All best, Angus

Thanks so much, Andy, for this terrific introduction to the music we’ll hear tonight, and for all the photo research that went into the notes, too.

Your web notes are a real value-added accompaniment to beautiful concerts; would that all performers we so attentive to their audiences!