June 12, 2006

Book 2.0

Episode 9: Improvised Delights

I began episode

seven with more thoughts about the classical music crisis. Classical music

had started to stagnate, I said. This was a fascinating kind of stagnation,

because in the midst of it there was lots of vitality. In the past 60 years,

since World War II, we've seen the rise of the early music movement, the rise

of musicology as a serious scholarly discipline, explosive new styles of new

music, new ways of staging opera, a far better (clearer, less idealized) view

of classical music history, an exploration of forgotten parts of the classical

repertoire, and much more, including the rise (in the US) of orchestras and

opera companies all over the country, along with attempts to make classical

music more accessible, and attempts to bring classical music and popular

culture together.

But at the same time, classical music began to turn in on itself; it

lost its popular touch. In some ways, this was the downside of some of the

excitement I've talked about. The expansion of the repertoire brought with it

an eruption of scholarship. Anyone willing to buy enough recordings could hear

all of Haydn's 104 symphonies, all of Bach's nearly 200 cantatas, and all of

Verdi's 26 operas, many of which had gotten obscure even during Verdi's

lifetime. But you can't encounter this music without also encountering (in

program notes, CD liner notes, and elsewhere) scholarly discussion of it. What

then gets lost is the direct appeal of the music. To talk about that, or at

least to talk about it without reference to classical music scholarship, is

somehow low-rent. And so the history of classical music starts to take on an

artificial life of its own. We're asked, for instance, to contemplate the

popular appeal of Verdi's operas, at the time when they were written, when

gigantic barrel organs trundled through Italian streets, playing Verdi tunes.

But what does that mean? Does it mean these operas should still be vital now,

because they were so popular when they were new? Does it mean that popular

music now might turn out to be as great--and long-lasting--as Verdi's operas?

It's hard to know, since neither possibility is ever mentioned. The popularity

of Verdi, in his day, becomes what we might call an abstract fact, one that's

savored by scholars--and thrust upon us in books and program notes--as if it

meant something, though what it means is never quite explained.

This scholarly, detached, analytical view of classical music then gets

translated into the formality of performances, the immobility and silence of

the musicians and the audience, and the lack of communication, the lack of any

explanation of what's really going on (which I've criticized so relentlessly in

earlier episodes). All this turns many people off, especially since it runs

directly against almost every trend in contemporary culture. So why should it be a surprise--as a consequence of everything I'm

discussing here--that ticket sales have fallen off? And so we have a crisis--a

serious one, if we look at the aging, shrinking audience. Classical music could

become financially unsustainable.

Which brings me to the first part of the book

proper, after the introduction. In that first part, I'll look in detail at the dimensions of the

crisis, giving as much data as possible on how bad it really is.

But before I do that, it's worthwhile--very valuable, in fact--to see

where the crisis comes from. And in fact it's part of a longer history. To look

at it, we have to roll the clock back to an earlier time, when Bach and Handel,

and then Haydn and Mozart, and of course many other fine composers, were all

active, even though the concept of classical music -- as we understand that now

-- didn't exist. Almost all the music anyone performed was music of the

present.

What was the music world like, without the burden of masterworks from

the past? It was very lively. Music was written for an audience, and the

audience reacted. Consider, for instance, the famous letter that Mozart wrote

to his father after the premiere of his

[I]n the midst of the first allegro [the first movement, at a quick

tempo] came a passage I had known would please. The

audience was quite carried away--there was a great outburst of applause. But,

since I knew when I wrote it that it would make a sensation, I had brought it

in again in the last--and then it came again, da

capo! The andante [the second movement, at a slower tempo] also found favor,

but particularly the last allegro [the last movement, which like the first was

fast] because, having noticed that all last allegri

here opened, like the first, with all instruments together and usually in

unison, I began with two violins only, piano [softly] for eight bars only, then

forte [loudly], so that at the piano (as I had expected) the audience said

"Sh!" and when they heard the forte began

at once to clap their hands.

Here are two things that don't fit our present notion of classical

music. First, Mozart wrote this piece to get a reaction from his audience. And,

second, the audience reacted right in the middle of the piece. The people in

Mozart's audience didn't remotely understand our concept of musical etiquette.

They clapped as soon as they heard something they liked.

What did this audience look like? [This is

the start of episode

eight.] There's a 1754 Canaletto painting ("London: Interior of the Rotunda at Ranelagh.") that shows an orchestral performance. The people

in the audience, as Christopher Small writes in his book Musicking,

"are standing or walking about, talking in pairs and in groups, or just coming

and going, in much the same way as people do in the foyer of a modern concert

hall....[B]ut there is a knot of people gathered around

the musicians' platform, as in a later day jazz enthusiasts would gather around

the bandstand in a dance hall when one of the great bands was playing for the

dancing." (Or as we'd see today in a rock club.)

Another

18th century painting of a musical performance

(Giovanni Paolo Pannini's "Musical

celebration given by the Cardinal de la Rochefoucauld

at the Theater Argentina in Rome in 1747 on the occasion of the marriage of the

Dauphin, son of Louis XV") shows what looks like a highly formal occasion,

with more than 70 musicians in the orchestra, plus singers, and many churchmen

in the audience. And yet people are chatting, and vendors are moving through

the crowd, selling drinks.

And

things got crazier than that. When Handel ran opera companies in London in the

early 18th century, he ran them as commercial enterprises, and nothing about

the performances was decorous. People in the audience shouted at the singers. On

stage there was spectacle, including flying, fire-breathing dragons. The

singers seemed exotic, even scandalous. And when Handel made the mistake of

engaging not just one, but two Italian prima donnas to sing at the same time, "a

great Disturbance happened at the Opera," as a London newspaper wrote, "occasioned

by the Partisans of the Two Celebrated Rival Ladies....The Contention at first

was only carried on by Hissing on one Side, and Clapping on the other; but proceeded at length to Catcalls, and other great Indecencies."

It ended, as a pamphlet from the time put it, with the "two Singing Ladies pull[ing]each other's coiffs?... it is

certainly an apparent Shame that two such well bred Ladies should call Bitch

and Whore..."

Our ideas of opera in this period -- Baroque

opera -- don't allow for anything like what I'm describing. Until very

recently, the conventional classical music wisdom (printed in books, taught in

music schools) was that Baroque opera was stylized and restrained. Which can't be true! Just look at how Richard Taruskin, in his five-volume

The liberties singers were

expected to take with the written music, and had to take or lose all respect,

would be thought a virtually inconceivable desecration today. But that was the

very least of it: the great Neapolitan castrato Gaetano

Majorano, known as Caffarelli

(1710-83)...was actually arrested and imprisoned, according to the police

report, for "disturbing the other performers, acting in a manner bordering on

lasciviousness (on stage) with one of the female singer, conversing with the

spectators in the boxes from the stage, ironically echoing whichever member of

the company was singing an aria, and finally refusing to sing in the ripieno

[the concluding "chorus" of principals] with the others...."

Now what sort of public would

tolerate such behavior, let alone delight in it?... That

audience, a mixture of aristocracy and urban middle class...was famed throughout

[At the request of a

reader, I've added citations for all my references. You'll find them at the

very end of the episode.]

So what would the

musical performances have been like, in these insane surroundings? (Or at least

insane by the standards classical music has today.) Of course they couldn't

have been stylized, restrained, or (often enough) even very decorous. Vivaldi, one of the great composers of the 18th century,

led performances of his operas by playing the principal violin part in the

orchestra. In keeping with the circus atmosphere of Italian opera houses, he'd

interrupt the singers by playing long, wild improvisations, in which (to quote

the liner notes for a recording of his opera Orlando finto pazzo)

"he flabbergasted audiences with sounds never before heard from a violin." Or as

an 18th century observer wrote, "Vivaldi played a

solo--splendid--followed by a cadenza that quite amazed me...he raised his fingers

until they were only a hair's breadth from the bridge, scarcely leaving room

for the bow--and this on all four strings, with imitations and incredible

speed." To put it more simply, he played as high and fast as possible, on all

four strings at once. Why would he do this? The answer seems obvious. He wanted

to put on a show, and to make himself the center of attention, so he'd be hired

to write and present more operas.

Handel--another of

the greatest Baroque composers--also seized attention when he led his operas

from the harpsichord in

How do we know that

they improvised? Because people wrote descriptions of what they did, textbooks

on how to do it, and transcriptions into musical notation of what musicians

actually played. Corelli, yet another of the great Baroque composers, composed violin music

that, as he wrote it down, often looks very simple. But he didn't mean

it to be played that way. He himself played it--especially in slow pieces--with

cascades of unwritten notes, which he'd make up on the spot, and play differently

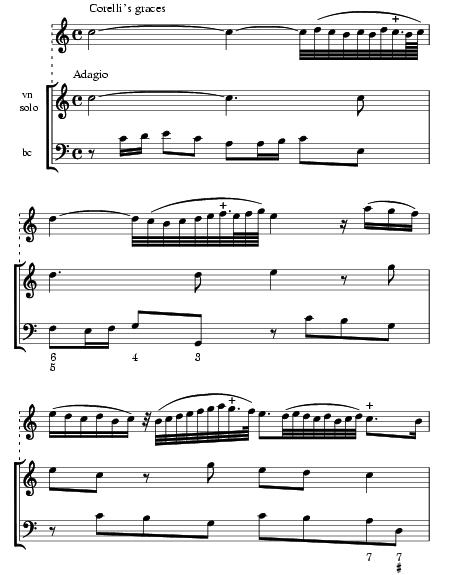

in each performance. Here's an example, printed in The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, the leading

classical music reference work. It comes from a 1710 edition of Corelli's violin sonatas (reprinted in 1716), which stated,

in no uncertain terms, that this is "how Corelli

wants one to play these pieces." Not, of course, that any serious musician

would simply copy what was printed, but (as the New Grove writer stresses) instead would take the printed score as

an example "to be emulated by the performer in his or her own manner." As you

can see, the musical notation vividly shows--even if you don't read music!--the

difference between what Corelli wrote down, and what

he expected to be played. The middle line shows what's written; the top line shows

how it should be played. (The music on the bottom is the bass line.)

How could these

embellishments change at every performance? Just look at the examples of

improvised music published in a famous 1752 book, Essay of a Method for Playing the Transverse Flute, by Johann

Joachim Quantz, an important 18th century musician.

In one chapter, Quantz gives 20 pages of examples,

ideas of what someone might do with simple musical passages. And I do mean

simple--the first of them is nothing more than the same note played three times:

dah dah dah. Quantz suggests 21 ways

to play those three notes, or rather to enhance them. It's as if you got up and

took three steps forward, 21 times, sometimes waving your arms, sometimes

spinning around at each step, sometimes adding steps sideways, sometimes

walking on tiptoes. Quantz's first variation simply

adds a flourish to each note: da-da-da-dah, da-da-da-dah, da-da-da-dah.

Other variations involve scales running up and down, or complex little

twists and turns, but always starting and ending on the same note, and

rhythmically dividing into three parts, so the relation to the original idea is

always clear.

And of course these

examples could be endlessly multiplied, because so many of them have come down

to us. Baroque opera, it turns out, was all about vocal embellishment, quite

apart from whatever fireworks composers like Vivaldi

and Handel could set off in the orchestra. Operas consisted almost exclusively

of solo arias. Each aria was divided into three parts, an opening section,

something else that contrasted with it, and then a repeat of the opening. In

the previous episode, I mentioned a basic misunderstanding of Baroque opera,

and it's all about this way of constructing an aria. As we see it now, it's

rigid, unyielding, stylized, even undramatic.

Once it begins, nothing's going to change. The music always comes back to the

place it started from.

But to 18th century

audiences--the people who sometimes screamed their approval, and sometimes

didn't pay attention to the music at all--this aria form (called the da capo aria, because da capo meant to repeat from the beginning, and that's what these

arias did) was nothing less than explosive. The whole point was to see what the

singers would do with the repeats. Of course they'd vary them. Of course, if

they were very good singers, they'd very them differently each night. So the da capo aria wasn't rigid, wasn't

stylized, and above all, wasn't boring. The variations could be wild; purists

repeatedly complained that the composer's melody would entirely disappear.

Whenever a singer stepped out to sing, anyone listening would wonder, "What's

he going to do this time? How wild is he going to get?" Or

how touching, how noble, how virile, how yielding, how melancholy, how

furiously angry, or how utterly despairing, depending on whatever emotion the

music was meant to convey. No wonder these audiences--or at least the

people who were paying attention--sometimes screamed. They were ravished,

excited, taken by surprise. And no wonder the singers tried so hard to amaze

the audience. How else could they make people pay attention?

But there was art in

all this, too. Stendhal, the great 19th century French novelist, loved opera,

and, to judge from some of his writing, must have gone to the opera every night

during a time when he lived in

In days gone by, the great singers, Babbini, Marchesi, Pacchiarotti, etc., used to compose their own ornamentation [all the italics in this passage

are Stendhal's] whenever the musical context required an exceptionally high

level of complexity; but in normal circumstances, they were concerned with extempore invention. All the various

categories of simpler embellishments (appoggiture, gruppetti, mordenti, and so on) were theirs to dispose and arrange

as they thought best, spontaneously, and following the dictates of their art

and their inner genius; the whole art of adorning the melody (i vezzi melodici del

canto, as Pacchiarotti used to call it, when I

met him in Padua in 1816) belonged by right to the performer. For instance, in

the aria

Ombra adorata, aspetta .. [from Vaccai's opera Giulietta e Romeo].

Crescentini would suffuse his whole voice and inflexion

with a broad and indefinable colouring of satisfaction, because it would strike

him, while he was actually standing up

and singing, that an impassioned lover about to be

reunited with his mistress probably would

feel something of the sort. But Velluti, who

perceives the situation rather differently, interprets the same passage in a

vein of melancholy, interspersed with brooding reflections upon the common

fate of the two lovers. There is no composer on earth, suppose him to be as

ingenious as you will, whose score can convey with precision, these and similar

infinitely minute nuances of

emotional suggestion: yet it is precisely these and similar infinitely minute nuances which form the

secret of Crescentini's unique perfection in his

interpretation of the aria; furthermore, all this infinitely minute material is itself in a perpetual state of transformation, constantly responding to

variations in the physiccal condition of the singer's

voice, or to changes in the intensity of the exaltation and ecstasy by which he

may happen to be inspired. At one performance, he may tend towards ornaments

redolent of indolence and morbidezza; on a

different occasion, from the very moment when the sets foot on the stage, he

may find himself in a mood for gorgheggi [cascades

of notes] instinct with energy and life. Unless he yield

to the inspiration of the moment, he can never attain to perfection in his

singing.

A book by Manuel

Garcia, Jr.,--a top 19th century singing teacher, and son of the man who created

the leading tenor role in Rossini's Barber

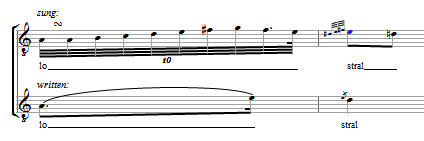

of Seville--gives many examples of 19th century vocal embellishments. In one

of them, while the orchestra rests, a tenor holds a long note, trilling on it,

and three times swelling his voice to make it louder, then pulling it back to

sing softly again; after this (and still, presumably, on the same breath), he

launches into gorgheggi. No singer could do that today; the

sound must have been astonishing. In other, simpler, examples, singers take the

written music, and--sometimes with very small changes--make it wonderfully personal.

Giuditta Pasta, who created the title role in

Bellini's Norma, takes little groups

of four notes from that music, and turns them into unexpected groups of five.

Garcia's father, in an excerpt from his Barber

role, adds a charming little flourish that bursts out like a delighted

smile (it's on the word "stral"):

Sometimes, Garcia

shows singers changing the rhythms the composers wrote, as if they were singing

jazz, in one case even losing the rhythm in the orchestra,

and going off for a moment on their own. This was a well-known expressive

effect, which pianists used, too, letting the melody in their right hand

diverge from the accompaniment their left hand played. In an 18th century book

on singing there's a touching example, reproduced in musical notation. Over a

simple bass line, a singer descends from a high note to a lower one, singing a

scale downward, but varying the length and loudness of each note, and lingering

over the descent, so that she makes the music entirely her own, feeling free to

finish a beat or two after the bass line does. As the writer, Pier Francesco Tosi,

says (with his 18th century Italian translated into 18th century English),

When on an even and

regular Movement of a Bass, which proceeds slowly, a Singer begins with a high Note,

dragging it gently down to a low one, with the Forte [loud] and Piano [soft],

almost gradually, with Inequality of Motion, that is to say, stopping a little more on some Notes in the

Middle, than on those that begin or end. Every good Musician takes it for

granted, that in the Art of Singing there is no invention superior, or

Execution more apt to touch the Heart than this...

And so it goes. Bach

improvised. Mozart improvised. Beethoven improvised, sometimes for an hour at a

time, sometimes making people cry, sometimes bringing a performance of his

chamber music to a halt:

...he played his Quintet for Pianoforte and Wind Instruments with Ramm as soloist [wrote someone from his time]. In the last

Allegro [the final movement, played at a fast tempo] there are several holds

before the theme is resumed. At one of these Beethoven suddenly began to

improvise [on the piano], took the Rondo for a theme and entertained himself and the others [the audience] for a considerable

time, but not the other players. They were displeased and Ramm

even very angry. It was really very comical to see them, momentarily expecting

the performance to be resumed, put their instruments to their mouths, only to

put them down again. At length Beethoven was satisfied and dropped into the Rondo

[resumed the final movement]. The whole company was transported with delight. [Though probably not the musicians.]

But then Beethoven

wasn't alone. Improvisation was a normal part of piano performances. Pianists

in the 19th century commonly improvised preludes to the notated pieces they

performed, a practice so widespread that there's even a name for it, "preluding." And even late in that century, when many of

these practices had mostly disappeared, a singer, finding a note in one of

Brahms's pieces too high to sing comfortably, asked Brahms if he could change

it, and Brahms said yes: "As far as I am concerned, a thinking, sensible singer

may, without hesitation, change a note which for some reason or other is for

the time being out of his compass into one what he can reach with comfort, provided always that the declamation remains

correct and the accentuation does not suffer." [emphasis

in the original]

So what does all

this mean? First, I think we misunderstand the music I've been talking about.

Nothing I've written here will come as surprise to musicologists; everything

I've mentioned (except perhaps the piano preluding)

is very well known. And yet performers today rarely do what would have been

done when the music was new. Singers singing Baroque opera, or Bellini or Rossini, barely ornament their music, at least

by 18th or 19th century standards. Da capo arias are

meticulously staged (the Metropolitan Opera's recent production of Handel's Rodelinda provides a lovely example) to show some

kind of motivation for the first-section repeat. The idea, now, is to show how

canny a dramatist Handel was; I've never seen a production, or heard one on any

recording, that treated the repeats first of all as occasions for vocal

display, and let Handel's drama emerge through that. René Jacobs, in his

recording of Handel's Rinaldo, at least lets the orchestra improvise

(or play written ornaments of the kind that would have been improvised); the

result is wonderfully fresh, a great surprise, both terrific art and irresistible

entertainment.

And so we lose the

spirit of the music, and, I might argue (Christopher Small certainly does), a

lot of the spirit of musicmaking itself. Why did this

happen? Because of the concept of classical music, which, as

we'll see, emerged in the 19th century, and put the composer at the center of

the musical universe. The purpose of playing music, at least in the

classical world, was to realize the composer's intentions, and that meant

playing the notes the composer wrote. And only those notes--even

when the composers themselves expected performers to add something of their

own. Historical research reveals, beyond any doubt, that this was

expected. But research is trumped by the orthodoxy of the present day, and even

some scholars get caught up in the contradiction. An important Mozart scholar,

Frederick Neumann, starts a discussion of improvised changes in Mozart's works

like this: "Mozart lived at a time when composers still gave the performer

license to make certain improvisatory additions to the written text." License!

Wham! Changes to the written text are, by their very nature, evidently suspect.

No wonder Neumann concludes that these changes should be very rare, as opposed

to other scholars (the pianist Robert Levin, for instance) who welcome them.

Compare that Neumann sentence to Neil Zazlaw, who in

his book on Mozart's symphonies happily talks about "Mozart's ornament-loving

instrumentalists."

So am I urging us to

return to some 18th century (or early 19th century) paradise? Hardly. There were many problems then. Performances, by our

standards, were very likely bad. Again by our standards, they were barely

rehearsed. Writers of the time complain about singers and instrumentalists who

introduced too many ornaments, making the music unrecognizable. (Note Brahms's

caution: Singers should only change the music if their changes didn't hurt it.)

Singers carried around "baggage arias," as they were called (because their

music was, as Stendhal says, "carried around permanently, as it were, like a change

of underwear"), which they'd introduce into every opera they sang. 18th century

orchestras seem to have improvised, with, sometimes, all the violinists

individually--and, you'd think, cacaphonically--adding

their own embellishments of the written violin line.

But let me say it

again. The spirit of those long-lost days is something we ought to recapture.

At the very least, we ought to know that we've lost it. And by losing it--by

evolving the concept of classical music, in which improvisation was all but

illegal--we may have sown the seeds for classical music's current decline.

This is the last book episode I'm going to

post until September. As I've said, I'm taking July off, and (with apologies to

everyone) will close this website to comments. If you find you're able to post

them, they won't show up on the site. I'll be back at work in August, but I'll

delay any further episodes till after Labor Day--when I'll talk about the idea

of classical music, and how it evolved. I suspect much of what I've been writing

in this episode and the last two will be shortened in the final book, or at

least I'll make them a little less academic. Have a terrific summer, everyone,

and feel free to make comments during the rest of June. I'll be happy to greet

you all again in the fall.

If you'd like to subscribe to this

book--which above all means you'll be notified by e-mail when new episodes

appear--just click here. Subscribers help me; I feel wonderfully encouraged

each time somebody new asks to be put on my subscription list. And feel free to

add a note to your e-mail. I'm always curious about who's subscribing, and why

you're all interested. That often leads to an e-mail exchange, and often enough

to some sharing of ideas (from which I learn a lot). Or let me put it this way:

Even if you don't work in the classical music business, you become part of the

network of people who've helped me with the book, which means (as I explained

in episode six) that the book is partly dedicated to you. I'll also offer

special goodies to subscribers--segments I haven't published online, revisions

of online episodes, the book proposal I'll eventually send to a publisher,

second thoughts on things I've written, special comments, and other things I

can't imagine yet..

Please comment on the book, too. Below you'll

see where you can post comments, which can either appear with your name

attached, or anonymously. Anyone who posts a comment of course also becomes

part of the network I'm so happy about. The comments have helped me enormously.

My privacy policy: I'll never share my

subscriber list with anyone, for any reason. I send all e-mail to my list myself, without routing it through anyone at ArtsJournal. And I send all e-mail with the names of the

recipients hidden. All subscribers have their privacy protected at all times.

Further: if you e-mail me about the book, I'll consider your e-mail private. I

won't quote it in any public forum without your permission. Comments you post

here, though, of course appear in a public forum, and thus can be freely quoted

by me or by anyone else who reads them.

Music that got me through this episode:

Comparisons between cut and uncut recordings of three operas, for an article on cuts I'm writing for Opera News. The recordings:

Wagner, Die Walküre, Solti studio recording,

with Hans Hotter and Birgit Nilsson, Wotan's

monologue in Act 2, uncut. I compared this to a live performance from

Wagner, Tristan und Isolde, Furtwängler

studio recording with Kirsten Flagstad and Ludwig Suthaus, first part of the love duet from Act 2, uncut.

Compared it to a 1936 live performance at

Donizetti, Anna Bolena, studio recording with Beverly Sills, Act 1 duet for Giovanna Seymour (Shirley Verrett) and Henry VIII (Paul Plishka), uncut. Compared to live 1957 La Scala performance with Maria Callas (Giulietta Simionato and Nicola Rossi-Lemeni in the duet), not just heavily cut, but virtually sculpted into a new opera written in a different musical style. The most striking musical moment in the duet, in this performance--an abrupt and bracing appearance of a new melody--is actually created by one of the cuts.

Citations:

Richard Taruskin, The

"Coping with Life

After Juditha," by Alessandro De Marchi

( translated by Charles Johnston), in liner notes to Vivaldi,

Corelli ornaments: Michael Collins/Robert

E. Seletsky: "Improvisation/Western Art Music/Baroque period/(iv) Later italianate embellishments," Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed June 11, 2006),

<http://www.grovemusic.com>

Johann Joachim Quantz, On Playing

the Flute [this is how the title is given in the English version], translated by Edward R. Reilly.

Stendhal, Life of Rossini, translated and

annotated by Richard N. Coe.

Pier Francesco Tosi, Observations on

the Florid Song, or, Sentiments on the Ancient and Modern Singers, translated

by J. E. Galliard.

Manuel Garcia Jr., Garcia's New Treatise on the Art of Singing

[Traité complet de l'art du chant].

piano right and left hand: Robert Philip, Early recordings and musical style: changing

tastes in instrumental performance, 1900-1950.

Thayer's Life of Beethoven,

revised and edited by Elliot

Forbes. Princeton:

Valerie Woodring Goertzen, "By Way of

Introduction: Preluding by 18th- and Early

19th-Century Pianists. The Journal of

Musicology, Vol. 14, No. 3 (Summer, 1996), pp.

299-337.

Michael Musgrave, A Brahms Reader.

Frederick

Neumann, Ornamentation and Improvisation

in Mozart. Princeton:

Robert

D. Levin, "Improvised Embellishments in Mozart's Keyboard Music." Early

Music, Vol. 20, No. 2, Performing Mozart's Music III. (May,

1992), pp. 221-233.

Neil Zazlaw, Mozart's

Symphonies: Context, Performance Practice, Reception.

John Spitzer and

Neil Zazlaw, "Improved Ornamentation in

Eighteenth-Century Orchestras." Journal

of the American Musicological Society, Vol. 39, No. 3 (Autumn,

1986), pp. 524-577.

Posted by gsandow on June 12, 2006 03:14 AM

COMMENTS

Post a comment

Tell A Friend