« October 2006 | Main | December 2006 »

November 3, 2006

I'll be back...

It's been a nutty week preparing for our Center's alumni conference today. I promise to be back in business next week, with thoughts and details on what we learn together. See you all then.

Posted by ataylor at 7:28 AM | Comments (0)

November 6, 2006

Encouraging the active audience

I just came out of a glorious weekend of thoughtful conversation among my program alumni, students, and guests, on the subject of the "active audience." Our two keynote provocateurs, Lynne Conner and Alan Brown, pushed us all to rethink how we think about audience experiences. And the many students and arts practitioners in the room took up the challenge with anecdotes, insights, and strategies to do so.

I'll try to convey elements of the event this week in my weblog. I'd love to begin, as the conference did, with the perspective of Lynne Conner.

Lynne is a theater professor, playwright, and consultant based in Pittsburgh. She lives with one foot in the world of academic rigor, theory, and perspective, and the other in the practitioner world, where budgets, organizational culture, and entrenched "best practices" push back against change. Over the past years, she has been working as a lead advisor to the Heinz Endowments' Arts Experience Initiative, encouraging several Pittsburgh arts institutions to engage audiences in a different way.

While many are complaining that today's audiences don't behave as they used to -- they won't sit still for long periods, they're resistant to the sacred spaces of quiet museums and concert halls -- Lynne's study of history suggests quite another thing. In fact, she says, the quiet, receiving audience is a fairly recent blip in history. Says she:

Up through the end of the nineteenth century, western audiences of all economic classes and from a wide variety of places were expected to be active participants before, during and after an arts event. Few conceived of the arts event as existing independently of its audience -- not the artists nor the producers nor the audiences themselves. In fact, there's plenty of evidence in the historical record to suggest that it was quite the opposite; the audience's presence was understood to be fundamental to the very definition of the arts event itself.

From ancient Athens to nineteenth-century America, audiences were expected to be highly interactive in defining the meaning and value of a cultural experience. In Athens, the entire citizenry (well, the men anyway) would take part in multi-day competitions to select the best tragedy of the year. In early theaters, audience members could move their seats around the chamber, talk amongst themselves, and interact with the actors or musicians on stage. In early American museums, citizens from all economic strata would wander ecclectic collections with picnic baskets to spend the day.

According to Conner, the passive, respectful, and quiet audience was not a historical ideal, but a construction of late nineteenth-century social and technology trends. Electric lighting shifted the audience into the dark for the first time in theater spaces, and emphasized the action on-stage. And America's social elite were seeking to define themselves against the lower classes by emphasizing the pure and perfect aspects of "high" art. Sophisticated audiences don't interrupt the artist's work with talk or movement or expressed opinion. They receive it as instruction, as gospel even.

So, how is this recent trend in behavior shifting back again to a historical norm? Stay tuned this week for more...

Posted by ataylor at 8:10 AM | Comments (3)

November 7, 2006

Encouraging co-authorship

So, what's an arts manager to do if the premise of yesterday's post is true (which it seems to be) -- that the history of audience interaction with art has been more active than passive, and that the current emphasis on sitting quietly and receiving art is an anomaly? What, especially, are you to do if your cultural facility was conceived and constructed during that anomalous moment in history? Are we even built for the kind of audience connection and collaboration our past suggests is the norm?

According to Lynne Conner and others at our recent conference, the answer is a challenge. We have certainly tried to build ''engagement'' through pre-show and post-show discussions -- although even many of these have been lectures or one-way conversations about what audiences should know about the work. And the art moment, itself, remains a sacred moment for many that shouldn't be altered or invaded with chatter (unless that's part of the moment).

Conner suggests that the solution lies in encouraging co-authorship -- inviting, supporting, and encouraging audiences to recognize and celebrate their active part in making meaning. She describes the requirement of that strategy:

This, then, is the practical, bottom line definition of co-authorship in the twenty-first century; a critical mass of surrounding arts experiences that converge in and around an arts event in order to provide useful information, opportunities to process that information through talk and other forms of personal expression, and finally, some kind of follow-through experience that allows for synthesis, analysis, debate and (at least some of the time) consensus on the meaning of the arts event itself.

For many artists and arts organizations, this is already their core value and purpose. For others, the idea might feel awkward and populist -- ''we must meet great art where it stands, there's no meeting in the middle'' they might say. But perhaps its the ''middle'' where the art exists in the first place. Not with the artist. Not with the audience. But in the electric space between them.

Just a thought. More to come.

Posted by ataylor at 8:16 AM | Comments (3)

November 9, 2006

Exploring the architecture of value

Continuing my summary of our recent alumni conference in Madison on The Rise of the Active Audience, our afternoon keynote meshed fabulously with Lynne Conner's morning conversation (discussed here and here). Alan Brown is among the leading audience research consultants and consumer behavior specialists in the arts these days. And his library of reports and articles on what he's learned make for compelling and useful reading (you can find many of them here).

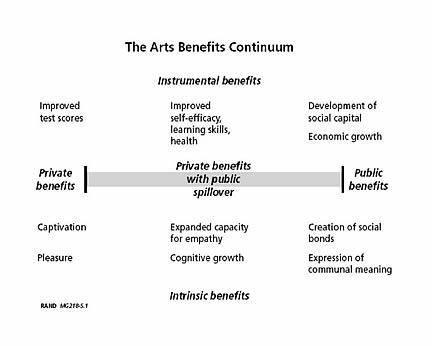

For the past year or so, Alan has been wrestling with the insights of the Wallace Foundation/RAND study, ''Gifts of the Muse", which mirrored many of his own discoveries in arts participation research, but conveyed that wisdom in a rather dense and impenetrable fashion (my words, not his). At the center of the RAND report was an odd and unintuitive graphic, exploring the intersection of two axes: "instrumental vs. intrinsic" benefits of arts experience, and "public vs. private" benefits. The idea was that there are individual and community benefits to arts experiences -- some affecting the participant, others "spilling over" into more public benefits in education, economics, and civic engagement. But the graphic and the narrative left many practitioners scratching their heads about what to do about that.

For the past year or so, Alan has been wrestling with the insights of the Wallace Foundation/RAND study, ''Gifts of the Muse", which mirrored many of his own discoveries in arts participation research, but conveyed that wisdom in a rather dense and impenetrable fashion (my words, not his). At the center of the RAND report was an odd and unintuitive graphic, exploring the intersection of two axes: "instrumental vs. intrinsic" benefits of arts experience, and "public vs. private" benefits. The idea was that there are individual and community benefits to arts experiences -- some affecting the participant, others "spilling over" into more public benefits in education, economics, and civic engagement. But the graphic and the narrative left many practitioners scratching their heads about what to do about that.

Alan's interpretation of the same concept changes the axes entirely. One axis breaks down the proximity in time to an arts experience ("during," "before/after," and "cumulative"). The other axis changes the "public/private" axis of the RAND model (which was confusingly political) to an "individual/community" axis...adding an "interpersonal" between the two (click the image for a larger view).

Alan's interpretation of the same concept changes the axes entirely. One axis breaks down the proximity in time to an arts experience ("during," "before/after," and "cumulative"). The other axis changes the "public/private" axis of the RAND model (which was confusingly political) to an "individual/community" axis...adding an "interpersonal" between the two (click the image for a larger view).

The resulting infographic is a rather compelling metaphor for how and when "value" and "benefits" from arts experiences form and accrue to individuals, to interpersonal relationships, and to the larger community. In the lower left of the graphic is the source of all impact...the arts experience itself. Alan describes this point in the model as a pebble dropping into a lake, causing ripples to move outward...sometimes for a lifetime. And the two axes mapped together lead to five clusters of value and benefit, that I'll drill into in my next post.

The resulting infographic is a rather compelling metaphor for how and when "value" and "benefits" from arts experiences form and accrue to individuals, to interpersonal relationships, and to the larger community. In the lower left of the graphic is the source of all impact...the arts experience itself. Alan describes this point in the model as a pebble dropping into a lake, causing ripples to move outward...sometimes for a lifetime. And the two axes mapped together lead to five clusters of value and benefit, that I'll drill into in my next post.

More thoughts to come on Alan's map and insights. We'll just let that ripple travel for a moment.

Posted by ataylor at 8:54 AM | Comments (3)

November 14, 2006

Architecture of value, part deux

Finally getting back to my summary last week of Alan Brown's 'Architecture of Value,' rethinking the RAND efforts on the values and benefits of arts experiences. Alan's model suggests five clusters of benefits, radiating out from the individual and 'in the moment' to the community and cumulative.

In a nutshell, the five benefits clusters are:

- Imprint of the Arts Experience

- Human Interaction

- Communal Meaning

- Personal Development, and

- Economic & Social Benefits

You can explore all the elements within each cluster through this three-page overview (pdf format).

So, what's an arts organization supposed to do with these benefit clusters? According to Brown, they're supposed to explore and define, as an organization, what benefits they believe they foster for their communities -- or, what benefits they strive to enable. As institutions serving the public trust -- and drawing on public funding and fiscal privelege to do so -- arts organizations should stive to understand, explain, and enhance their specific public, interpersonal, or individual goals. Then they should align their organization to deliver on those goals in more rich and meaningful ways.

Does that mean board members and administrative leadership should make artistic decisions? Not necessarily. But Alan suggests that all leaders of the organization should be part of the conversation. Says he in this Grantmakers in the Arts Reader article:

I hope for a time when board members of arts organizations sit down on a regular basis with both administrative and artistic staff and talk about the benefits they seek to create for their communities. Then, perhaps, board and staff will have something more to talk about than fundraising. Most board members are unprepared to participate in artistic decision-making -- thats not their job -- but they are eminently qualified to set overarching guidelines for how their organization can respond to community needs and create value. That is their job.

Speaking of Grantmakers in the Arts, I'm just now attending their Boston conference. Responses and insights from this convening to come...

Posted by ataylor at 12:11 AM | Comments (1)

November 16, 2006

Haggling vs. higher ground

A few weeks back, my MBA program hosted fellow blogger Drew McManus for a mock orchestra negotiation exercise. The idea was for the students to play professional symphony musicians working on a collective bargaining agreement (CBA) with Drew, who played the management of a fictious symphony. Drew went on quite a bit about the experience. Although, as with real-life multi-party negotiations, his perspective of the process is one of many.

The set-up was a CBA process between professional musicians and orchestra management, in which the background and budget documents were horribly incomplete, inaccurate, and perhaps even intentionally vague. These errors were part of the simulation, of course, building on Drew's experience with the quality and clarity of financial and organizational information provided by management to musicians.

These errors and inconsistencies were fairly quickly exposed by the mock musician team, who then refused to make a counter offer. They suggested that there was no meaningful basis upon which they could negotiate, and only evidence to the contrary that any mutual decision would be effectively managed. Drew mentioned that real-world musicians would always make a counter-offer, and that the bargaining process required them to do so. The mock negotiating team stood their ground, determined that no negotiation was possible with a management that was at least incompetent and at most intentionally deceitful.

A lively exchange ensued, but the negotiations never continued.

Of course, much of this tension and disdain was built into the simulation, to give students the flavor of the experience from the artist's side of the table. In many cases, musicians are certainly met with incomplete or inaccurate information during negotiations. And in many cases, the operating needs of both sides require that they negotiate anyway to keep paychecks and concerts flowing, even though both sides know they are ignoring the larger problems.

But I came away from the exercise struck by two things:

- That collective bargaining within professional orchestras is among the most depressing and structurally fraught processes of any cultural endeavor. And that those orchestras that manage it successfully (and there certainly are many) do so despite the structure rather than because of it.

- That the common bias -- particularly in the symphony world -- that management and musicians are on opposite sides of that bargaining conversation is both destructive and untrue (although I'll admit it's a persistent myth). There is tension between the preferred strategies and tangible outcomes, to be sure, but the ultimate goal seems quite the same: vitality, sustainability, excellence, and expression.

I know that all of this is easy for me to say. I'm not a professional orchestral musician, nor am I an orchestra administrator. Fair enough. But if the simulation experienced by my students was even marginally close to reality (and I'm assured by several that it's not unusual), very few of these passionate, creative, and insightful students will decide that it's worth the grief.

Posted by ataylor at 10:31 AM | Comments (5)

November 17, 2006

Separate and connected...like a giant fungus

Last week I had the pleasure of speaking to a gathering of arts leaders from around the Midwest, hosted by the Alliant Energy Foundation and intended to build partnerships and connections in the arts across state lines. I went on a bit about my usual problems with the myths and metaphors of ''partnerships,'' which strike me as both widely accepted, and essentially flawed.

Partnership, I suggested, reinforces a false idea...that we are somehow separate to begin with, and that connection only comes in conscious effort and initiative. Instead, I believe arts organizations and initiatives are fundamentally connected already -- whether or not we take action to connect ourselves.

As I was preparing for this conversation, Googling for a metaphor, I found (again) the glorious story of the Armillaria ostoyae, or the ''honey mushroom.'' And now I can't get it out of my head.

The particular mushroom in question lives and grows in the Malheur National Forest in eastern Oregon. Upon inspecting the ecosystem to determine why so many trees were dying, scientists discovered that the outcroppings of mushrooms around the forest were actually all part of one, single organism. About three feet underground lived the root network for this fungus, which turned out to be the largest living organism ever discovered on earth: 3.5 miles across, taking up the equivalent of over 1600 football fields, and likely over 2400 years old (perhaps even 7200 years).

The particular mushroom in question lives and grows in the Malheur National Forest in eastern Oregon. Upon inspecting the ecosystem to determine why so many trees were dying, scientists discovered that the outcroppings of mushrooms around the forest were actually all part of one, single organism. About three feet underground lived the root network for this fungus, which turned out to be the largest living organism ever discovered on earth: 3.5 miles across, taking up the equivalent of over 1600 football fields, and likely over 2400 years old (perhaps even 7200 years).

So, you say, arts organizations are like a humungous fungus? Well...yes.

Consider any profound moment you've experienced in the arts. As an artist or an audience member, that moment likely seemed like a single moment, but was in fact an outcropping of a much deeper and more ancient root. That moment was likely built on a lifetime of experiences in the arts and in your life -- lessons, school, relationships, family events, books, values, passions, fears -- all brought to the surface by the resonance of a creative or cultural experience.

And since that powerful moment was the product of all moments that came before it, no single arts organization can lay claim as its producer.

Which brings me back to ''partnership.'' To my mind, especially in the world of creative expression, our separateness is only a convenient myth to help us do our work. We certainly have different corporate structures, different boards, different budgets, different buildings. But these are functional fictions hiding a deeper truth.

Our collective work in the arts is connected in both practical and profound ways. 'We can either pretend to ''partner'' as separate entities, or inform the connections that already course between us.

Posted by ataylor at 6:58 AM | Comments (1)

November 21, 2006

Does 'smart business' trump good governance?

Forbes has an opinion piece on board governance in the corporate world, calling into question Apple's board appointment of Google's CEO, while Steve Jobs is already a powerful force on Disney's board. In theory, the article says, boards are supposed to be uniquely focused on the interests of a corporation's shareholders, not playing multiple games at once.

Says one expert on the corporate boards:

"When executives take outside board seats at firms where they do business or where they hope to do business, they raise the odds that these potential conflicts will ripen into real ones.... If they do ripen, the only ways to mitigate these conflicts are to (1) step back from considering certain issues in the boardroom or (2) step down from the board."

In corporate America, the issue of interlocking boards raises questions about free markets and true competition (see a more academic exploration of the issues here). In the nonprofit world, the challenge of interlocking boards is less about competition, and more about mission and public trust.

I'm sure that if most communities did an inventory of all of their nonprofit board members over the past decade, they would see a short list of business and community leaders shuffling between multiple nonprofits. And while the shared governance might resonate with my post last week about the giant mushroom (we're all connected, so why shouldn't our boards be?), it's well worth some thoughtful analysis.

What is the utility and the hidden cost of cycling the same board members among many nonprofits, either through concurrent or sequential terms? Does the short list of active board members in any community limit or expand the health and innovation of the organization's being governed? And even if it's a system that can't be reversed, how might we leverage that system for better results (perhaps more focused and sustained board training for those ''high-end'' governance wonks)?

The Forbes piece concludes by suggesting that good results may supercede concerns about policy and protocol violations, and that interlocking boards may indeed offer more good than ill:

In this case, it may be true that having directors who are really smart and deeply connected may make more sense than adhering to the strictest notions of independence. The jury is still out on this one, of course, but smart business may very well trump good governance.

In other words, perhaps abandoning our ethics, standards, and responsibility to shareholders is okay if we can turn a profit.

Posted by ataylor at 9:58 AM | Comments (1)

November 22, 2006

If we want to measure the arts, we'll need new metrics

During the recent Grantmakers in the Arts conference in Boston, the issue of measurement continued to rise and fall in various sessions. After all, if arts grantmakers are in the business of positive change (or sustaining positive things), they inevitably wonder how they're doing in delivering on that promise. Such evaluation requires both a target and a measure of progress toward that target.

The challenge is in applying existing metrics (dollars, headcounts, activity, test scores) to such complex and hazy goals (truth, beauty, pleasure, wisdom). To this task I humbly submit the following metrics, already spinning around the world for other purposes.

- hedon

a single unit of pleasure, already used in ethical mathematics (don't ask, I don't know) - milliHelen

the amount of physical beauty required to launch one ship - warhol

a unit of fame or hype lasting exactly fifteen minutes. Some useful multiples from the Wikipedia include:- kilowarhol -- famous for 15,000 minutes, or 10.42 days. A sort of metric "nine day wonder."

- megawarhol -- famous for 15 million minutes, or 28.5 years. The type of person your parents talk about all the time, but of whom you've never heard from anyone else.

If we really hunker down, we could suggest a USRDA for each of the above (U.S. Recommended Daily Allowance). And each cultural production could publicly post the detailed value of its contents: ''Tonight's performance of Romeo and Juliet contains 250 hedons, 950 milliHelens, and 14.9 megawarhols.''

Posted by ataylor at 9:12 AM | Comments (2)

November 27, 2006

More ways to express your public self

Social networking technology is vastly changing the face and nature of the web, and how individuals use it. Massively popular user-driven sites like MySpace or Flickr or YouTube enable users to share their voice and vision with a wider world -- in photos, in videos, in text, in network connections, in playlists of favorite music.

Now, sites like Dandelife are adding the variable of time to the mix, allowing users to build a graphic timeline of their life, complete with essential events and stories from birth to school to love to travel to loss. The site even allows users to connect their timeline to their Flickr and YouTube accounts, attaching their narratives to media they posted elsewhere.

Now, sites like Dandelife are adding the variable of time to the mix, allowing users to build a graphic timeline of their life, complete with essential events and stories from birth to school to love to travel to loss. The site even allows users to connect their timeline to their Flickr and YouTube accounts, attaching their narratives to media they posted elsewhere.

Like other social networking sites, Dandelife allows and encourages connections between users -- allowing any user to add any other user as friend or family or fan, and encouraging building or reflecting on other peoples' stories through simple buttons and links.

The arts have always been a place where communities tell collective stories, connect to the stories among them, or explore the stories of distant worlds -- in paint, in music, in dialogue, in movement, in three-dimensional form. It will be fascinating to watch what happens to that trusted and honored role as individuals gain greater power to create and connect their stories on their own.

NOTE: For a flavor of how these technologies might work more specifically in the arts, take a look at The Saatchi Gallery's new on-line homebase/networking site for art students, or the nascient performing arts review hub, AudienceBuzz.com.

Posted by ataylor at 12:08 AM | Comments (1)

November 29, 2006

The non-representative fundraising photo (that works)

Jeff Brooks of Donor Power Blog has a thoughtful post on the tension between the actual work of a nonprofit, and the perceptions or messages that attract contributed income. His case in point is ''Old Man Eating,'' a perennial fundraising photo archetype used among urban rescue missions. ''Old Man Eating,'' or OME as Brooks and his colleagues call the class of images, is extraordinarily effective in eliciting passion and contributions. It makes for a successful campaign.

The problem is, Brooks suggests, that OME is not particularly representative of the predominant clients of urban rescue missions (women with children and young adults), and that staff and leadership are getting tired of a tactic that doesn't quite feel true.

But it works. Says Brooks:

It's fundraising dissonance. The image that touches people's heart, that motivates them to give is Old Man Eating. Even though he's not the real picture of the need. Even though these very same donors know that helping younger people is more needful and impactful. The fact is, the decision to give is an emotional one, not a rational one. Emotional triggers, not rational ones, are those that motivate giving. And OME is a potent emotional trigger.

Brooks' response? Acknowledge the dissonance, and get over it. Says he:

Meet donors where they are -- not where you wish they'd be. Put forth the need that motivates them to respond. Then, you'll find, you earn the right to have the conversation with them about what you do, and who you (and they) serve. Those who are ready to move beyond the gut reaction to OME will do just that.

So, what image of your work are your donors buying? And does it have anything to do with the true picture of what you do? If not, do you have a problem with that?

Posted by ataylor at 11:35 AM | Comments (1)

November 30, 2006

A good prospect for a (virtual) board member, perhaps

Anshe Chung has all the elements of a good prospect for your nonprofit board -- she's a millionaire, a real estate mogul, and an innovative entrepreneur with an eye for design and aesthetic value. While it's true that she's not technically a real person, but an avatar...an on-line character in the virtual world of Second Life...her influence, and her money, is real.

Chung is the construct of a Chinese-born language teacher living near Frankfurt, Germany, who has been developing virtual real estate in virtual worlds for a while now. The practice is well established in multi-user on-line environments, where users can not only buy ''land'' but create and sell ''objects'' to other users. The difference with Second Life is that the virtual currency used in the on-line universe is convertable to U.S. dollars (at about 250 to 1).

Chung is the construct of a Chinese-born language teacher living near Frankfurt, Germany, who has been developing virtual real estate in virtual worlds for a while now. The practice is well established in multi-user on-line environments, where users can not only buy ''land'' but create and sell ''objects'' to other users. The difference with Second Life is that the virtual currency used in the on-line universe is convertable to U.S. dollars (at about 250 to 1).

Chung amassed her millions by buying up islands and exclusive areas of the Second Life universe, developing them with mansions, landscapes, and other such virtual amenities, and imposing strict zoning rules to keep the riff-raff out and the paying customers in. The CEO of the company that produces Second Life describes Chung as ''the government'' for her sequestered islands and continents (more details in this Wikipedia entry, and this Business Week article).

Strange and brain-bending stuff, to be sure. But a glimpse, perhaps, into the multiple worlds -- on-line and off-line -- where creative individuals and entrepreneurs will be creating their work. And if you think this doesn't apply to the lively arts, think again. The proposed New Globe Theater in New York already commissioned and opened a virtual version of the venue in Second Life. Says their overview of the effort (scroll down the page to the August 14 news item):

Strange and brain-bending stuff, to be sure. But a glimpse, perhaps, into the multiple worlds -- on-line and off-line -- where creative individuals and entrepreneurs will be creating their work. And if you think this doesn't apply to the lively arts, think again. The proposed New Globe Theater in New York already commissioned and opened a virtual version of the venue in Second Life. Says their overview of the effort (scroll down the page to the August 14 news item):

Since opening its doors, the New Globe has become the rock star of virtual destinations and the it-stage for cultural and intellectual exchange. In-world guest speakers on the stage have ranged from the Editor-in-Chief of Wired Magazine to the Governor of Virginia. The opening performance featured actors from around the globe who had never met in person ... though time difference for rehearsals did prove a REAL problem!

The real governor of Virginia held a virtual town hall meeting in that virtual performing arts space back in August. Is the world weird enough for you yet?

Posted by ataylor at 9:13 AM | Comments (4)