« April 2008 | Main | June 2008 »

May 1, 2008

Three words, three problems

During the recent Association of Arts Administration Educators conference here in Madison, the increasing proficiency and professionalism around our collective conversation was both a source of pride, and a cause for pause. As a field of educators, researching and teaching cultural management and leadership, we're clearly growing in reflection, connections, and success. But what if we're doing so at a time when the profession, as we've defined it, is changing rapidly? What if we're all getting increasingly proficient at a decreasingly relevant part of the ecosystem?

Consider, for example, the three-word phrase that often crops up at such conferences: ''professional arts organization.'' This phrase captures, in shorthand, the specific category of cultural endeavor we tend to be discussing. Professional arts organizations require professional management, aesthetic integrity, curatorial control, and stable but responsive structures to hold them together while moving their mission forward. These are the standards that drive our teaching and learning about the field.

But each of those three words -- ''professional,'' ''arts,'' and ''organization'' -- is in radical flux at the moment. That suggests that a phrase (and an assumption) combining all three could mean less and less in shorthand form.

This concern may come from my current reading matter, Clay Shirky's new book Here Comes Everybody, about the increasing opportunities for collective action without traditional organizational structures -- think Flickr or Wikipedia or iStockPhoto. But there's something rumbling in the world that questions our basic assumptions about arts and cultural management. Let's take a look at each word in the phrase, in reverse order:

- Organization

The formal organization (social, commercial, political, etc.) evolved in response to a set of structural barriers to collective action. Work that required more than one or a few people to complete -- highway systems, national defense, mass-produced goods, save-the-spotted-owl initiatives, performing arts touring networks, museums -- created large problems of coordination, alignment of resources (enough money in one place under one decision system), and high transaction costs (everyone having to agree every time...exhausting). The organization resolved these challenges through formalized decision structures, consolidated resources, and persistent identity (for example, a corporation lives separately from its founders, and is endowed with many/most of the rights of an individual). There was a cost to this structure, to be sure. A significant portion of any organization's energy is consumed by self-maintenance rather than delivering on its purpose. Since the option was to not do the thing at all, we figured the costs were acceptable and necessary.

With the evolution of digital communications networks and software, however, many of the original challenges that required an organization are gone or significantly reduced. Collective action is increasingly available to distributed groups who don't even know each other by name, and may convene around a cause only to disburse thereafter. The cost of production and distribution has dropped to almost zero for many goods and services. Organizations are still necessary and essential parts of the mix, but they're not the only (or even the optimal) solution to every question, as they once were. - Arts

There's little need to go on about this particular word, which we all would agree is a fast-moving, increasingly amorphous creature. When we talk about ''arts'' in the context of ''arts management'' or ''arts organizations,'' we still generally mean predominantly Western forms of expression, with an assumed emphasis on technical or aesthetic excellence. We don't always mean this, of course. But if you nudge most conversations by professionals, you'll find this assumption just beneath the surface. Evidence comes from the fact that we still add qualifiers to the word when we mean something other than the above: ''community arts,'' ''amateur arts.'' - Professional

Specialized organizations in specialized industries require specialized professionals -- trained in the task by formal process or apprenticeship. Professionals earn the term when they are paid for their specialized work and when the nature and frame of their efforts are defined and evaluated by their peers rather than by their customers. Professional writers define what professional writers do. Professional doctors and realtors define the parameters and certifications for their peers.

But, again, what happens to the word ''professional'' when works of comparable quality and skill can be conceived, produced, and distributed without expensive or centralized means of production? Flickr has millions of exceptional images, many shot by individuals with no formal training, expecting no pay, and unfiltered by a traditional gatekeeper (curator, publisher, agent). Says Shirky:

When reproduction, distribution, and categorization were all difficult, as they were for the last five hundred years, we needed professionals to undertake those jobs, and we properly venerated those people for the service they performed. Now those tasks are simpler, and the earlier roles have in many cases become optional, and are sometimes obstacles to direct access, often putting the providers of the older service at odds with their erstwhile patrons.

So, am I suggesting that we abandon our foundational phrase ''professional arts organization''? Of course not. As long as there are complex processes, specialized physical requirements of expression (theaters, museums, even on-line forums), and a recognition of the value of extraordinary skill, vision, and voice, we will need organizations, professionals, and filtering systems to find, foster, and connect expressive works to the world.

But we may want to recalibrate our underlying assumptions as an industry (and as educators who hope to advance that industry and its goals) about the specific role of what we now call ''professional arts organizations.'' These are a subset of a massive ecology available to us to achieve our larger purpose. If we stick too rigidly to our terms, we may become obstacles to the missions we claim to have.

Posted by ataylor at 9:27 AM | Comments (5)

May 7, 2008

Because art *is* context

In the visual art equivalent of the much-blogged-about Joshua Bell in the subway experiment, a Belgian arts channel placed an influential contemporary painter out of context to see who would take note. How many stopped to watch Luc Tuymans painting? About four percent.

It's a bit of a rigged experiment in both cases, as commuters and street-wanderers often have something else on their minds. But it underscores the importance of context, place, and focus to so much artistic work. It also makes me wonder what would happen if both Bell and Tuymans had some training from an accomplished busker (which, perhaps, is a good way of describing the arts administrator's role in the system).

Posted by ataylor at 8:09 AM | Comments (4)

May 8, 2008

Creating space for play

One of my MBA students (thanks Michal) connected me with this useful article about creative play and its importance in childhood development. I particularly like the list of tips for facilitating play (included below). It seems that cultural managers could use some version of this list in many situations, by substituting the word ''children'' with '' staff,'' ''artists,'' ''board members,'' ''audiences,'' ''volunteers,'' and the like.

Let the play begin.

Facilitating children's play

Young children need a balance of opportunities for different kinds of play, indoors and outdoors. They need the support of knowledgeable adults and parents who do the following:

- Provide long, uninterrupted periods (45-60 minutes minimum) for spontaneous free play.

- Provide a variety of materials to stimulate different kinds of play--blocks and construction toys for cognitive development; sand, mud, water, clay, paint, and other open-ended materials for sensory play, dress-up clothes and props for pretend play; balls, hoops, climbing places, and open space for gross motor play.

- Provide loose parts for play, both indoors and out, and encourage children to manipulate the environment to support their play.

- Consider the opportunities for challenge and age-appropriate risk-taking in play.

- Ensure that all children have access to play opportunities and are included in play.

- Let children play for their own purposes.

- Play with children on their terms, taking the occasional ride down the slide, or putting on a hat and assuming a role in pretend play.

- Recognize the value of messy play, rough-and-tumble play, and nonsense play.

- Understand that children need to feel a sense of belonging to the play culture of childhood.

- Take an interest in their play, asking questions, offering suggestions, and engaging eagerly as co-players when invited.

Posted by ataylor at 10:46 AM | Comments (2)

May 9, 2008

Visualizing the connections

Thanks to Lex Leifheit's reference to one of my posts, I found a really cool programmatic innovation through one of her posts (such is the way the weblog world works). The DAISY system provided by New Haven's International Festival of Arts & Ideas encourages visitors to explore the entire content of the festival through many different angles: genres, events, themes, and artists.

DAISY (aka, ''Dynamic Arts & Ideas Search Yielder'') offers a branching graphic view of the festival programs. With a specific event at its center (like a Liz Lerman lecture, for example), the graphic offers related artists, events, themes, and genres...each of which can be selected to become the new center of the exploration.

DAISY (aka, ''Dynamic Arts & Ideas Search Yielder'') offers a branching graphic view of the festival programs. With a specific event at its center (like a Liz Lerman lecture, for example), the graphic offers related artists, events, themes, and genres...each of which can be selected to become the new center of the exploration.

It's an intriguing response to an age-old problem in cultural programming -- how to slice, dice, and segment a season or series of events in a way that simplifies choice, but doesn't presume a particular bias (clustered by genre, or artist, or discipline, or even price). DAISY seems to allow for multiple entry paths, and to encourage a more organic approach to the material for the prospective audience.

I'll be really interested to see how festival-goers use the system, and whether it leads them to find or select events they might not have otherwise connected.

Thanks Lex!

Posted by ataylor at 8:25 AM | Comments (2)

May 12, 2008

Attendance vs. engagement

Three foundations -- Pew, Wallace, and Philadelphia -- are ponying up $6.3 million to boost cultural engagement in Philadelphia over the next 12 years. It's a bold initiative by any measure, but vulnerable (already it seems) to some common sandtraps around goals and means.

The biggest sandtrap is to conflate observed attendance with ''engagement'' or ''participation.'' The observation usually presumes you have a specific frame to do your counting (attendance at professional arts events). And the attendance expectation usually means you want more volume, rather than more impact.

Even this short article goes back and forth between volume and depth, beginning with a goal to ''double audience participation at area arts events over the next 12 years,'' and ending with an emphasis on casting a wider net (at least around how ''engagement'' is defined...although still with a bias toward more formal cultural experience).

So, what's the problem? Nothing necessarily. More money to help arts organizations engage their audiences and communities is a good thing. More inclusive metrics to measure their success (the proposed ''Cultural Engagement Index'') can be extraordinarily helpful in focusing long-term strategy, as well.

The trick in advancing ''cultural engagement,'' however, lies in truly embracing the complexity of the concept, and the many channels that facilitate it. A rich cultural ecology includes thousands of entry points and connections -- some small portion of them provided by nonprofit, professional arts organizations. The larger universe of ''engagement'' and ''participation'' is provided by informal groups (book clubs, knitting circles, amateur photographer clubs), commercial venues (paint-your-own pottery, Home Depot, the local music store), and social organizations not primarily about the arts (churches, schools, social services, hospitals). Funding by arts-focused foundations and alliances tends to favor the professional, nonprofit arts (understandably so), even though that part of the system has little influence on the rest.

It should be fascinating to watch how this initiative becomes operational -- what projects are funded, what measures emerge, and what outcomes (attendance vs. engagement) take precedence when the two are mutually exclusive.

(Thanks to Mark for the link and the thoughtful commentary.)

Posted by ataylor at 8:44 AM | Comments (3)

May 13, 2008

Even when the big-boned lady sings, it ain't over

When you're in the business of building loyalty and coaxing repeat purchase from your audiences (and aren't we all?), a positive experience with your programming is only part of the battle. The real impact comes in how the experience is remembered over time. Brain science is starting to discover how and why the actual experience and the remembered experience can be radically different.

This article from Miller-McCune describes recent discoveries about the brain that suggest our memories don't evolve linearly from experienced fact (called ''verbatim'' memory) to remembered essence (called ''gist''). But rather, these two systems are working simultaneously. Says the article:

When an event occurs, verbatim memory records an accurate representation. But even as it is doing so, gist memory begins processing the information and determining how it fits into our existing storehouse of knowledge. Verbatim memories generally die away within a day or two, leaving only the gist memory, which records the event as we interpreted it.

The two tracks of encoding can sometimes lead to a disconnect between what actually happened, and what the individual remembers:

Under certain circumstances, this can produce a phenomenon [experimental psychologist Valerie] Reyna and her colleagues refer to as ''phantom recollection.'' She calls this ''a powerful form of false alarm'' in which gist memory -- designed to look for patterns and fill in perceived gaps -- creates a vivid but illusory image in our mind.

Not that we should all toy with the minds of our audiences (or, should we?), but the discovery of verbatim and gist running in parallel does suggest some strategic opportunities for cultural managers. For example, can we create an environment in which patrons remember neutral experiences favorably, or in which positive experiences are encoded in gist memory with an extra boost?

Since we all tend to construct the context and relevance of an experience within groups, rather than alone (social semiotics anyone?), we might have important opportunities to rig the game in the moments following a cultural experience -- or in spaces within one. Any effort to help an audience member bring relevant context to the experience before, during, and after might help, as well.

In essence, verbatim and gist memory suggest that the performance may be over when the fat lady sings, but the encoding and recollection of that performance will take days to find its shape.

Posted by ataylor at 8:45 AM | Comments (0)

May 14, 2008

You are here

If you haven't yet explored Google's ''Street View'' feature (described here, available in many area Google Maps), you should really take a moment to do so. For place-based cultural organizations (those with a building as part of their mission delivery), it offers a powerful way to connect web visitors with your actual place.

Essentially, Google hires a car with a 360-degree camera and a global positioning system to drive around taking pictures every dozen yards or so. The images are then attached to Google Maps, so you get not only an overhead street map and satellite view, but also a view from the street facing all directions. You can even wander up and down the street to view the shops, restaurants, and amenities nearby.

Essentially, Google hires a car with a 360-degree camera and a global positioning system to drive around taking pictures every dozen yards or so. The images are then attached to Google Maps, so you get not only an overhead street map and satellite view, but also a view from the street facing all directions. You can even wander up and down the street to view the shops, restaurants, and amenities nearby.

As with most other Google maps, you can grab some pre-formatted code to embed these street views into your own web site, or send them via phone or e-mail, providing what used to be a complex and sophisticated web site feature with little effort and no cost.

Street View is not available in every U.S. city yet (Google just added Madison in March). But even as I write this, I'm sure the little Google camera cars are winding their way around the country, whistling far and wee.

Posted by ataylor at 8:20 AM | Comments (1)

May 15, 2008

One letter, big difference

Greg Sandow lobs a compelling argument in the National Performing Arts Convention blog, encouraging us to decouple ''art'' and ''the arts'' in our thinking and our planning. Says Greg:

Art is an activity, sometimes sublime, and also the result of that activity. By now we know -- or certainly we ought to know -- that it might be found anywhere, in vacant lots, in silence and graffiti, in overheard remarks (see the poetry of Jonathan Williams, an advocate of outsider art, who died not long ago), and in popular culture. The arts, by contrast, are a set of interest groups, whose claim to glory (and to funding) is that they speak for art, which is only partly true. They don't speak for all art, and when someone speaking for the arts -- by which I mean for the interest groups -- says that only the arts can offer meaning in our society, we've strayed so far from reality that we might as well be jumping off a cliff.

I don't agree that many (or even most) nonprofit arts organizations claim to speak for all of the arts (I know, hyperbole makes blogging more fun...I do it all the time). And I tend to see the cluster of entities we now call ''the arts'' as an important subset of expressive enterprise rather than a set of interest groups. But Greg's larger point is right on the money (on the subsidy, I suppose).

Nonprofit, professional, excellence-focused cultural organizations aren't more noble, more worthy, or more representative of art. They are a particular means of producing, delivering, and preserving forms of human expression that don't fare well in commercial or informal markets. We've certainly extracted cash and contributions from claiming a unique and important place in that larger system. But from this point forward, that same claim of separateness will only serve to diminish our position in and our impact on the world.

It will be interesting to see how the argument pans out during the National Performing Arts Convention. I'll be there to listen and watch, along with a team of academics and graduate students commissioned to do just that. More on that project soon...

Posted by ataylor at 8:44 AM | Comments (2)

May 20, 2008

Fail early, fail often

Lucy Bernholz flags an important and awkward issue in her Philanthropy 2173 blog: the essential link between innovation and failure. If we're truly committed to fostering innovation and risk-taking in our organizations' artistic and management efforts, failure should be a key indicator of our attempts to do so.

If you've ever taught someone to ice skate or downhill ski, this indicator is obvious. If you don't fall frequently, you're not trying hard enough. You're stiff and conservative in your motion, unwilling to commit, and therefore more slow to learn.

And yet, where is the expectation and even celebration of failure in the metrics of major foundations, major donors, and board meetings? And where is our strategy, modeled in some industries, to ''fail earlier, fail faster and reallocate the resources from the failures''?

So, at your next staff meeting, raise a coffee mug to a recent project that went horribly wrong. Someone should be congratulated.

Posted by ataylor at 8:07 AM | Comments (3)

May 22, 2008

Mass creativity

CrowdSpring is a new web resource that hopes to bring ''crowdsourcing'' to the daily lives of creative individuals. The site allows any individual or company to post a design need (generally logo designs at the moment), along with escrow funds to pay their promised fee, and then anyone can design and post a response. The response the client likes the best gets paid out of the escrowed funds. The others don't.

While it may seem a bit brutal for the designer side (an individual could create a ton of spec designs and never get chosen), the system at least sets out a clear set of rules for the game.

It will be interesting to see if more complex design demands can be satisfied through this system (a logo can take a few minutes or a few hours to design...if you're only generating initial ideas...a full branding effort can take months). I wonder, for example, if anyone will post a request for a new composition.

In the short term, it's an interesting alternative for low-resource organizations to get high-quality (or at least high-volume) designs. In the long term, it may be a new way creative work gets done.

Posted by ataylor at 8:39 AM | Comments (7)

May 23, 2008

Do music degree programs create professional musicians?

There's growing conversation among conservatories and other arts-focused degree programs in higher education about what it is they're actually preparing students to do. The unspoken assumption has often been that music, theater, and related degrees are intended to develop artists of high technical excellence, prepared (at least technically) for professional work as artists.

Of course, many more students graduate from these programs than could ever find employment in the cultural world. And, in fact, many enter such programs not to become professionals, but to immerse themselves in an endeavor that they love.

To learn more about the outcomes of arts training programs, including conservatories in higher education, the Surdna Foundation just launched a new research initiative, the Strategic National Arts Alumni Project (SNAAP). Says the report web site:

Arts alumni who graduated 5, 10, 15 and 20 years earlier will provide information about their formal arts training. They will report the nature of their current arts involvement, reflect on the relevance of arts training to their work and further education, and describe turning points, obstacles, and key relationships and opportunities that influenced their lives and careers.

The effort should yield intriguing results, certainly useful results for any arts training program that wants to bring clarity and intent to its work.

Posted by ataylor at 8:21 AM | Comments (6)

May 28, 2008

Phase shift

While we've all be eyeing the Internet as the transformative social technology of our generation, another less glamorous device has been quietly vying for the title. According to the International Telecommunications Union, almost half of the world's population had a mobile phone in 2007, with the most significant growth in developing countries.

Mobile phones are certainly everywhere, in every demographic. And while the technology is increasingly mundane -- make a call from anywhere, send a text message, ho hum -- technology often has its greatest social impact when it becomes ubiquitous or ''normal.'' Or, says Clay Shirky, ''We have reached an age when this stuff is technologically boring enough to be socially interesting.''

What does it mean for arts organizations that almost everyone in their audience has a mobile phone? Or that more and more are communicating by cryptic text messages (up to 2.3 trillion messages in 2010 according to Gartner)? As I've said before, something dramatic happens to a system when more than half of its parts are interconnected.

I've seen lots of conference and think-tank discussions about the Internet and how arts professionals can advance their work on-line. But we've had precious little discussion about the less exciting but perhaps more impactful role of the mobile phone -- especially on the global stage. It might be time for some public thinking on the subject.

Posted by ataylor at 8:24 AM | Comments (2)

May 29, 2008

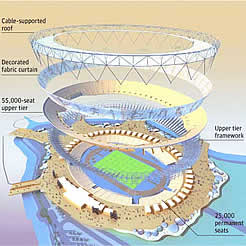

How about a movable performing arts center?

The Guardian reports on an emerging scheme to make London's stadium for the 2012 Olympic games a portable affair. Post-Olympics, they would deconstruct it, and send it to the next Olympic city host (perhaps Chicago). Reduce, reuse, recycle, indeed.

The Guardian reports on an emerging scheme to make London's stadium for the 2012 Olympic games a portable affair. Post-Olympics, they would deconstruct it, and send it to the next Olympic city host (perhaps Chicago). Reduce, reuse, recycle, indeed.

The innovation is driven by the staggering costs of hosting the Olympics -- particularly in capital investment -- and the temporary community need for a venue of such proportions. The two cities would share the costs, and both would get a stadium of sufficient size for the big event (I suppose the second city could then put the venue on eBay or CraigsList).

While the technology and design seem radically new, the concept is at least as old as the traveling circus. They called it the ''Big Top Tent.''

Posted by ataylor at 11:54 AM | Comments (4)