Boccatango / Joyce Theater, NYC / July 26 – August 12, 2004

The New York dance audience knows Julio Bocca best from his star turns with American Ballet Theatre. These days, he’s also starring in Boccatango, teamed with members of Ballet Argentino, the company he leads back home in Buenos Aires. This touring vehicle is neither classical ballet nor tango, though. Rather, it’s a show in which the choreographer Ana Maria Stekelman exploits both genres (as well as modern dance and jazz) to produce an entertainment more fit for a cabaret than the concert stage.

Item: Bocca, in a sheer black singlet and tango trousers, gets cozy with a stark black table, using it as a support for some gymnastic skirmishing, as a cage, and as a surface from which to cantilever himself into space. Just when you’re belatedly getting the idea that it’s his bed, and that his antics indicate his sexual fantasies, along comes the girl of his dreams—an exquisitely svelte little thing, all flexibility and precision, without a smidgen of soul. After she struts her stuff, however, she’s claimed by a different guy, a big, attractively thuggish type, their doings half apache dance, half something we’re often treated to by the Ailey company.

Item: Now it’s Bocca’s turn to get the gal. No need to cry for him, Argentina. A more mature woman than the earlier vision arrives, clad for after-hours office work, you might say, in a black tailored suit. She then strips it off to dance with Our Hero in nothing but (working downward) a bikini bra, a thong, and sheer black thigh-high stockings. Bocca’s got nothing on now but his abbreviated skivvies, and before long she decides to keep him company in his bare-chested state. (At this point, the lighting dims to that low orangey glow that indicates sensitivity to the standards of the local decency squad.) Like most fantasies, the lady doesn’t last long.

Item: Dead center on an otherwise dark stage, an overhead light beams down on a way tall raw-wood ladder. Just in case you weren’t already saying “uh-oh” to this set-up, a dry ice fog has rolled in from the wings. It disperses to reveal the bare-chested Bocca lying supine under the ladder, looking as if he’s been sacrificed, perhaps martyred. But no, he rises, and you notice he’s wearing a pair of tough gloves to protect his hands for the upcoming feats of strength, balance, and sheer nerve he will attempt on the rickety prop. So in a very few minutes we go from implications of New Testament agony to the modest acrobatic achievements of a small traveling circus. What this may have to do with dancing is anybody’s guess.

As for the rest of the program, there are group numbers, in some of which the fact that the tango, historically, used male-male partnering is co-opted to create a sensation. There are myriad opportunities throughout (perhaps a few too many) for Bocca to display his grand jeté—ballet’s familiar striding-the-air leap, which he makes sharp and buoyant at the same time—and his whiz-bang turns. There is, predictably, a dance involving chairs (clearly bought in a job lot with the table we saw early on). There are even a couple of comic turns (don’t ask, I beg you, I’m doing my best to forget).

All this (and more, mercilessly more) has musical accompaniment from a small group of instrumentalists (bandoneon player included, natch) and a pair of vocalists—the lady in question doing a serviceable job that is a shade pathetic, the gentleman lacking both the voice and the personal charisma that is necessary to his trade.

The most extraordinary thing about this dismaying show is that it’s the very antithesis of the tango, a dance form celebrated for its sultry, sinuous rhythms; its sensuous range of emotion, from the raw to the subtle and mysterious; its ability to evoke a mood of nostalgia, even about the present. Boccatango is sanitized and, in every possible way, over-miked.

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

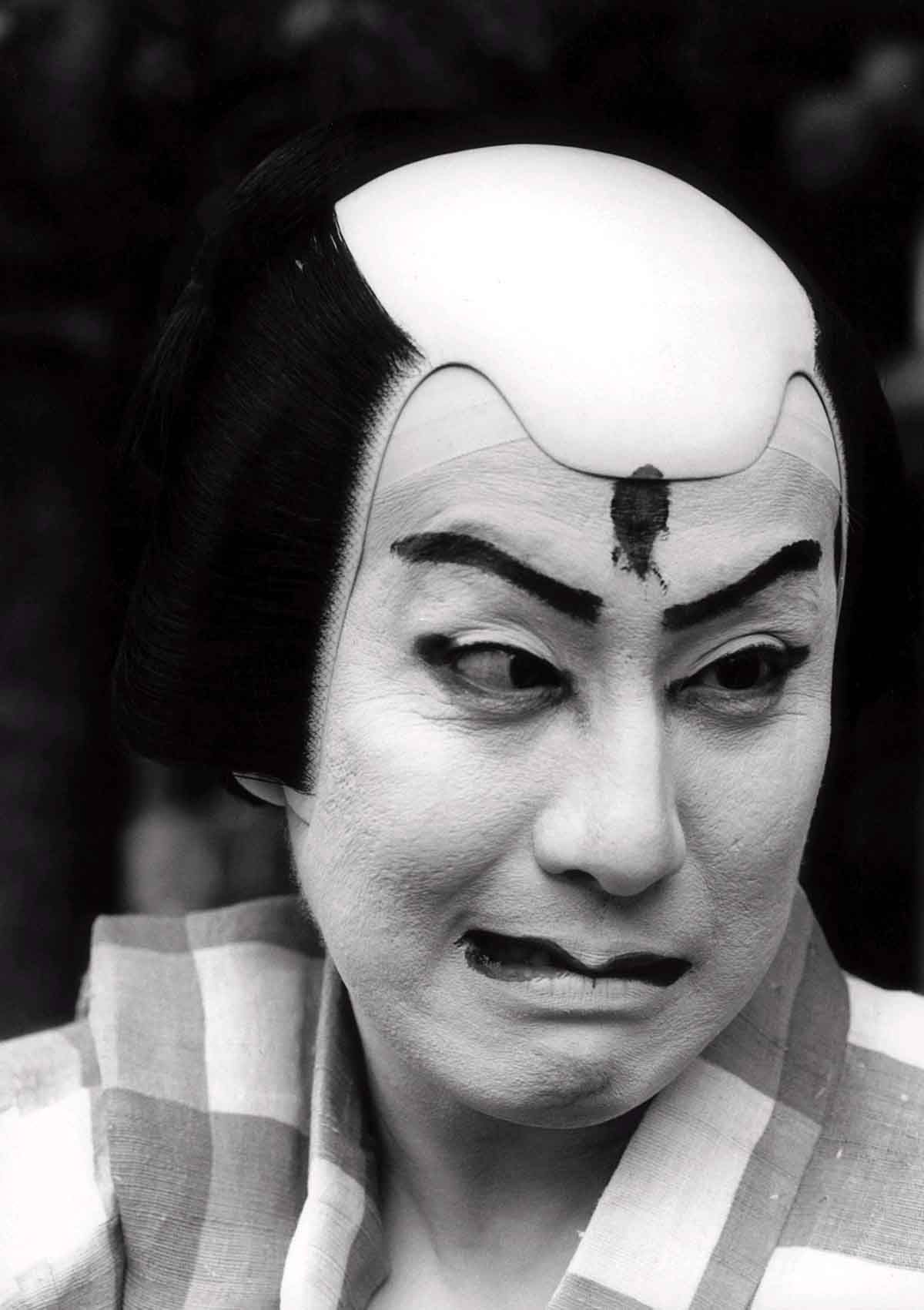

In a temporary theater in Lincoln Center’s Damrosch Park designed to replicate a traditional venue for Kabuki performance, Japan’s Heisei Nakamura-za company condensed to three hours a play that takes a full day to unfold in its unabridged state. Natsumatsuri Naniwa Kagami (The Summer Festival: A Mirror of Osaka) encompasses domestic comedy and domestic tragedy, low humor and high melodrama, keen psychological observation and spectacular combat—all evoked via the vividly stylized means of an art form that’s been riveting audiences for over 400 years. Despite the damage done to the story by compression (surely the original paid more attention to the soulful highborn youth at the center of the plot); despite the fact that the only performance I could get admission to was a dress rehearsal at which the simultaneous translation broke off halfway through; despite my uneasy feeling that I was seeing tradition much influenced by the age of video games, two scenes promise to stay with me for a good long time.

In a temporary theater in Lincoln Center’s Damrosch Park designed to replicate a traditional venue for Kabuki performance, Japan’s Heisei Nakamura-za company condensed to three hours a play that takes a full day to unfold in its unabridged state. Natsumatsuri Naniwa Kagami (The Summer Festival: A Mirror of Osaka) encompasses domestic comedy and domestic tragedy, low humor and high melodrama, keen psychological observation and spectacular combat—all evoked via the vividly stylized means of an art form that’s been riveting audiences for over 400 years. Despite the damage done to the story by compression (surely the original paid more attention to the soulful highborn youth at the center of the plot); despite the fact that the only performance I could get admission to was a dress rehearsal at which the simultaneous translation broke off halfway through; despite my uneasy feeling that I was seeing tradition much influenced by the age of video games, two scenes promise to stay with me for a good long time.

Helpmann and Ashton himself were danced, respectively, by Anthony Dowell (the great Apollonian danseur of his generation, who then directed the company) and Wayne Sleep (a diminutive, ebullient artist who has not forgotten he was once a high-flying virtuoso). The present incumbents are perhaps a shade too outlandish, and of course the audience encourages them. Ashton himself achieved a nuanced portrayal–part Dickensian, part Chekovian–that was as touching as it was amusing.

Helpmann and Ashton himself were danced, respectively, by Anthony Dowell (the great Apollonian danseur of his generation, who then directed the company) and Wayne Sleep (a diminutive, ebullient artist who has not forgotten he was once a high-flying virtuoso). The present incumbents are perhaps a shade too outlandish, and of course the audience encourages them. Ashton himself achieved a nuanced portrayal–part Dickensian, part Chekovian–that was as touching as it was amusing.