Beginning January 6, I’m planning to go to the New York City Ballet a lot.

I haven’t gone to the NYCB a lot in years. My attendance started falling off after Balanchine’s death in 1983, because, without the man there—as creator, coach, teacher, and all ‘round inspirational force—performances of his ballets deteriorated, slowly but inexorably.

No room here for the placing of blame. After all, it’s a birthday party! The New York City Ballet, naturally the main custodian of Balanchine’s work, is celebrating the 100th anniversary of the choreographer’s birth with, this season, seven weeks of repertory performances.

Just look at the schedule: On paper, at any rate, it makes me weep with pleasure. Well, almost. Six of the season’s eight weeks will blessedly be dominated by all-Balanchine programs. The only non-Balanchine works on the mixed bills are Fokine’s Chopiniana (aka Les Sylphides) and Bournonville’s Flower Festival at Genzano pas de deux, both demonstrably germane to Balanchine’s history.

Just look at the schedule: On paper, at any rate, it makes me weep with pleasure. Well, almost. Six of the season’s eight weeks will blessedly be dominated by all-Balanchine programs. The only non-Balanchine works on the mixed bills are Fokine’s Chopiniana (aka Les Sylphides) and Bournonville’s Flower Festival at Genzano pas de deux, both demonstrably germane to Balanchine’s history.

During this period, the sole departure from the canon will be seven performances of Broadway choreographer Susan Stroman’s new program-length Double Feature, an oblique homage to Balanchine’s work for the commercial stage and no doubt a necessary provision for an audience ravenous for novelty, as audiences invariably are. Balanchine’s own work for Broadway will be represented by Slaughter on Tenth Avenue, from On Your Toes.

The two final weeks of the season will be given over to The Sleeping Beauty, its landmark Petipa choreography reconfigured by Peter Martins, with Balanchine’s hand present only in the Garland Dance. This ensemble waltz, in which little- and big-girl students intertwine with adult couples who are full-fledged professionals, was Balanchine’s nostalgic tribute to the legendary Maryinsky school and company in which he was bred. Decades later, he contemplated the possibility of producing the whole ballet for the NYCB, but that project, sadly, never came into being. Yet even in Martins’s version—which assumes that today’s viewers are too impatient to tolerate, let alone appreciate, the expansive leisure of the nineteenth-century classics—Beauty serves to remind us of the ways in which Balanchine absorbed and extended Petipa’s aesthetic principles.

Martins’s full-length Swan Lake will also be given several showings, though Balanchine devotees might well prefer Mr. B’s one-act version—an inventive “essence of Lake”—that has all but disappeared from the active rep. The short version has become a curiosity; the long version insures good box office.

The season’s schedule makes a related concession to the preferences of today’s paying public by giving over a disproportionate number of slots to Balanchine’s program-length works, Coppélia, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, and Jewels, the last really a trio of ballets tenuously connected by an idea and a set, two of them perfectly capable of standing alone. Balanchine’s most substantial achievement lies in his shorter works, most of them abstract or, like Serenade, hauntingly semi-abstract. Still, audience surveys—and consumer preference controls what happens on the concert stage almost as firmly as it rules the world of commerce—have proved without a doubt that today one long ballet with a story sells best. Balanchine himself might have agreed that this is an oddly retrogressive state of affairs.

But just imagine: There will be programs like Apollo, Serenade, and Prodigal Son (January 22) and Donizetti Variations, Concerto Barocco, and Scotch Symphony (February 7, matinée). Not a dud, not a Martins or a Wheeldon or an also-ran among them. (Jerome Robbins will get the inclusion due him in the spring season.) This is surely an occasion both for reveling in the genius of Balanchine and seeing, without the usual distractions, how the first post-Balanchine generation has nurtured its formidable legacy.

So here’s my plan: I go. I look. I make notes. (I always make absurdly copious notes. Note taking at a dance performance is not merely a journalist’s tool for supporting inadequate memory. It’s a device that lets her believe for a foolish moment that she’s capturing the ephemeral.) Next morning latest I post my informal report on what I believe I saw and what I made of it. The subject and the set-up lends itself to blogging, don’t you think?

© 2004 Tobi Tobias

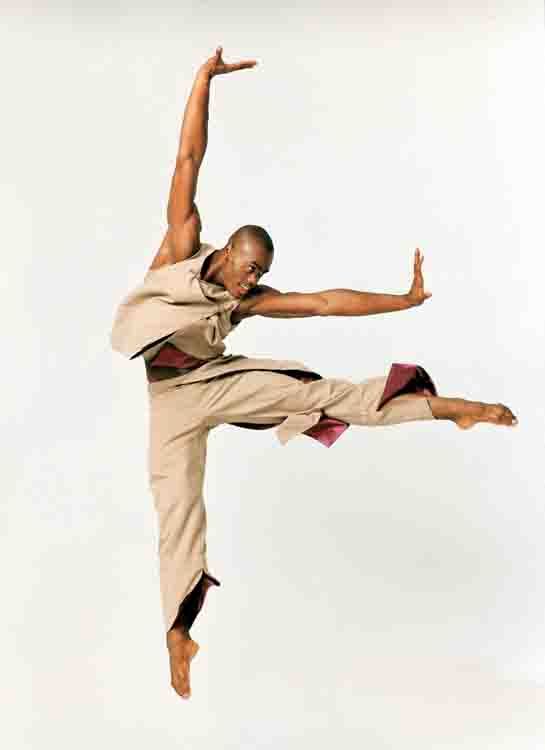

Corollary to this aim ran the impulse to proclaim the multi-faceted beauty of black culture by depicting its people in moments of joy, play, and celebration.

Corollary to this aim ran the impulse to proclaim the multi-faceted beauty of black culture by depicting its people in moments of joy, play, and celebration. Jennifer Muller’s Footprints, the best of the lot, depicts a clan of pilgrims

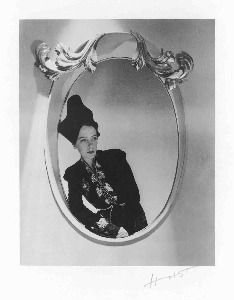

Jennifer Muller’s Footprints, the best of the lot, depicts a clan of pilgrims If Schiaparelli was not a beauty, neither was she a belle-laide, as is sometimes claimed.

If Schiaparelli was not a beauty, neither was she a belle-laide, as is sometimes claimed.

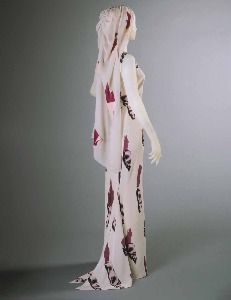

Dalí was incontestably Schiaparelli’s primary Surrealist influence (and collaborator).

Dalí was incontestably Schiaparelli’s primary Surrealist influence (and collaborator). Schiaparelli also linked up with the sweet ironies of Cocteau’s poetic vision, translating a pair of his continuous-line drawings into embroidered images on apparel.

Schiaparelli also linked up with the sweet ironies of Cocteau’s poetic vision, translating a pair of his continuous-line drawings into embroidered images on apparel. glamour, creating a kind of chic noir.

glamour, creating a kind of chic noir. Accessories were central, not peripheral, to Schiaparelli’s work.

Accessories were central, not peripheral, to Schiaparelli’s work. During World War II, Schiaparelli took shelter in the States, where she refused to design, manifesting her solidarity with her French colleagues, stymied in their work by the Nazis.

During World War II, Schiaparelli took shelter in the States, where she refused to design, manifesting her solidarity with her French colleagues, stymied in their work by the Nazis. Doug Varone boldly (recklessly, if you will) co-opted Stravinsky’s Firebird score for his contribution, The Beating of Wings, but apart from some references to the old Russian tale that the composer drew on and the ballets subsequently choreographed to the music (Fokine’s the first and finest among them), he essentially made a Varonesque work.

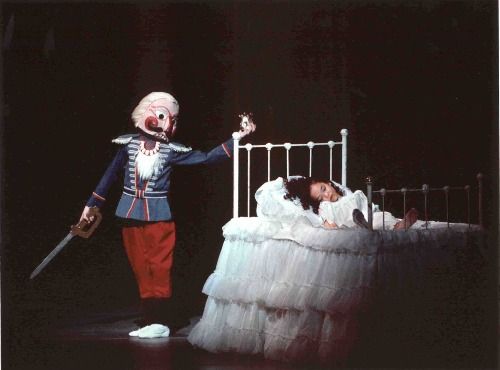

Doug Varone boldly (recklessly, if you will) co-opted Stravinsky’s Firebird score for his contribution, The Beating of Wings, but apart from some references to the old Russian tale that the composer drew on and the ballets subsequently choreographed to the music (Fokine’s the first and finest among them), he essentially made a Varonesque work. The Nutcracker

The Nutcracker January 22, 2004 marks the 100th anniversary of George Balanchine’s birth. The celebratory “year” that is wrapped around this propitious date follows the art and social worlds’ custom of beginning in the fall and extending through the following spring. It has been and will continue to be filled with activities centering on the man who shaped twentieth-century ballet according to his singular vision. No end of exhibitions, archival undertakings, film and video screenings, symposiums, and – most important – productions of the ballets worldwide are calling attention to Balanchine’s genius. (A continually updated schedule of the happenings is available at

January 22, 2004 marks the 100th anniversary of George Balanchine’s birth. The celebratory “year” that is wrapped around this propitious date follows the art and social worlds’ custom of beginning in the fall and extending through the following spring. It has been and will continue to be filled with activities centering on the man who shaped twentieth-century ballet according to his singular vision. No end of exhibitions, archival undertakings, film and video screenings, symposiums, and – most important – productions of the ballets worldwide are calling attention to Balanchine’s genius. (A continually updated schedule of the happenings is available at