What do you see when you look at the logo here on the right?

What do you see when you look at the logo here on the right?

Some people might see the equivalent of money — that is, the sign of a non-profit funding group. Burlington Magazine saw “a lowered neckline that appears to announce a mail-order firm for adult lingerie.” And a year ago, the Fitzwilliam Museum of Cambridge University was so turned off by it that the powers-that-be there decided against applying for £80,000 in funding to acquire “The Dead Christ” by Marcantonio Bassetti because the logo would have had to be placed beside the work. Director Timothy Potts told The Art Newspaper at the time that it would be “an unacceptable distraction” and “the currency of marketing.”

![]() But the May issue of The Art Newspaper has a short item revealing that the director of The Art Fund, Stephen Deuchar, has bowed to the criticism, chucked the teddy and introduced a new logo, also at right. The lingerie is gone, but the hot-pink heart remains.

But the May issue of The Art Newspaper has a short item revealing that the director of The Art Fund, Stephen Deuchar, has bowed to the criticism, chucked the teddy and introduced a new logo, also at right. The lingerie is gone, but the hot-pink heart remains.

Potts would undoubtedly still object, but plenty of other museums are willing to go along with the Fund, which was started in 1903 and which annually awards about £4 million in grants to British museums and galleries.

The other day, The Art Fund announced the four finalists for its annual £100,000 prize, which will be announced on June 30. The finalists are the Blists Hill Victorian Town, the Herbert Art Gallery and Museum, the Ulster Museum and the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

This year, this Fund is allowing people to vote for their favorite, saying that the judges will take the tallies and the comments into account. No other promises, which is good.

Will the judges take the opportunity to give the money to Oxford in a “take that, Cambridge” stance? We’ll see.

To my mind, the Tate Modern should be a bigger museum role model than the Guggenheim Bilbao, which has succeeded for complex reasons — not just because it’s a museum-building-as-destination. (For example,

To my mind, the Tate Modern should be a bigger museum role model than the Guggenheim Bilbao, which has succeeded for complex reasons — not just because it’s a museum-building-as-destination. (For example,  It sounds so simple, so non-controversial. What’s the big deal?

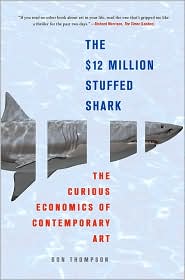

It sounds so simple, so non-controversial. What’s the big deal?  So on the eve of the bellwether spring contemporary art sales, I went back to Thompson for Five Questions. Curiously, Thompson doesn’t list the book on his

So on the eve of the bellwether spring contemporary art sales, I went back to Thompson for Five Questions. Curiously, Thompson doesn’t list the book on his