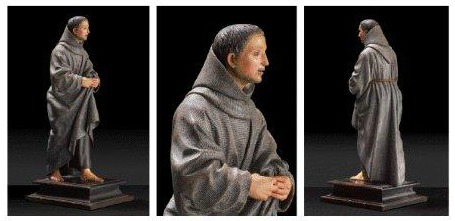

The San Diego Museum of Art is well-known, deservedly, for its collection of  Spanish art — including work by such masters as El Greco, Zurbarán, Goya, and Sorolla. The other day, it announced an acquisition that complements those works: It’s a Spanish baroque sculpture, a polychromed wood piece by Pedro de Mena (1628–1688).

The museum calls Mena “among the greatest sculptors of the Spanish Baroque.” This work depicts San Diego de Alcalá and was created around 1665. Nice touch, buying a saint whose name is on the city!

John Marciari, Curator of European Art, said in the press release announcing the acquisition that “we have for several years sought a significant piece of Spanish Baroque sculpture to add to the collection. The San Diego is precisely the sort of work we had in mind. Pedro de Mena’s extraordinary realism is the counterpart to our still life by Sánchez Cotán, while the ecstatic expression of the saint reminds one of our great Saint Peter by El Greco.”

John Marciari, Curator of European Art, said in the press release announcing the acquisition that “we have for several years sought a significant piece of Spanish Baroque sculpture to add to the collection. The San Diego is precisely the sort of work we had in mind. Pedro de Mena’s extraordinary realism is the counterpart to our still life by Sánchez Cotán, while the ecstatic expression of the saint reminds one of our great Saint Peter by El Greco.”

Luckily for the museum, it had received a $7.4 million bequest from the Estate of Donald W. Shira recently, and drew on those funds for this purchase. It did not disclose the price for the piece, which is more than two feet tall.

Roxana Velásquez, the museum’s director, made the most important point in the release, imho: “Since my arrival, one of my ambitions has been to build on the great collection of European art already in San Diego. The new work by Pedro de Mena strengthens our collection of Spanish art. Combined with the acquisition of the Portrait of Don Luis de Borbón by Anton Raphael Mengs that we acquired last year, we are expanding important holdings for San Diego.â€

It’s important for directors to see their collections that way — creating distinguishing collection, not like everyone else’s — and equally important for them to articulate that to the world.

More details about the artist and the work here.

Photo Credit: Courtesy of the San Diego Art Museum