When I visited The Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky at the Metropolitan Museum on Saturday afternoon, I was prepared to be delighted–and I was, in more ways than one.

When I visited The Plains Indians: Artists of Earth and Sky at the Metropolitan Museum on Saturday afternoon, I was prepared to be delighted–and I was, in more ways than one.

The Nelson-Atkins Museum, which co-curated the show with the Musee du Quai Branly in Paris, had primed me for how beautiful it was going to be, sending along the catalogue as evidence when the show opened in Kansas City last fall. At the Met, the exhibit lived up to my great expectations.

So many of these objects are stunningly beautiful.

But from the very first one in the Met’s installation, I noticed that something was different about this exhibit. For what I think is the first time in the museum’s history, the Met has labeled these works as by artists, rather that using what has become tradition in most art museum for Native American works–merely identifying the tribe from which the object comes.

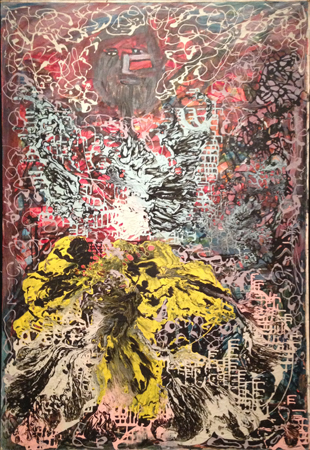

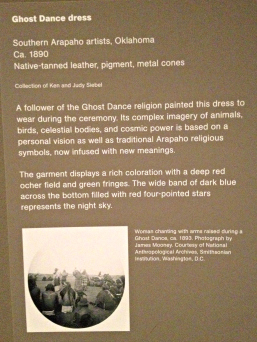

So when you see the “ghost dance dress” at the top of this post, you will see in the label I have posted below that it was made by “Southern Arapaho artists” in Oklahoma. No, we do not know their names, but identifying the piece as by artists acknowledges it as a work of art, rather than an enthographic piece.

So when you see the “ghost dance dress” at the top of this post, you will see in the label I have posted below that it was made by “Southern Arapaho artists” in Oklahoma. No, we do not know their names, but identifying the piece as by artists acknowledges it as a work of art, rather than an enthographic piece.

You may recall that I wrote a Page One Arts & Leisure section article about this for The New York Times in 2011, when the Denver Art Museum was leading the way.

The nut paragraph said:

Art museums have collected American Indian objects for decades, but, like natural history and anthropology museums, they have tended to treat them as ethnographic pieces, illustrative of a culture. Wall labels have generally steered clear even of the “anonymous” designation commonly used for Western artworks of unknown authorship and in cases where Indian artists left signature marks — as Chilkat weavers of the Pacific Northwest long have, for example — this evidence has often been ignored.

Later, the article read:

“Recognizing that Native American art was made by individuals, not tribes, and labeling it accordingly, is a practice that is long overdue,” said Dan L. Monroe, executive director of the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Mass., which has a large Indian collection and has made some attempts to identify individual artists since the mid-1990s.

And, explaining how Bill Holm, a pioneer in trying to identify the hand that created many anonymous Native American works was thinking about the problem:

And, explaining how Bill Holm, a pioneer in trying to identify the hand that created many anonymous Native American works was thinking about the problem:

Just as the creator of an altarpiece in the Uffizi Gallery in Florence is called the “Saint Cecilia Master,” the maker of a 19th-century Haida chief’s beautifully carved chair in the Field Museum in Chicago is the “Master of the Chicago Settee.”

In my 2011 article, I reported that many museums were not updating their collections to reflect this new trend because it costs a lot to make and install new labels. So, on Saturday, I went downstairs at the Met to see what was happening in its Native American galleries.

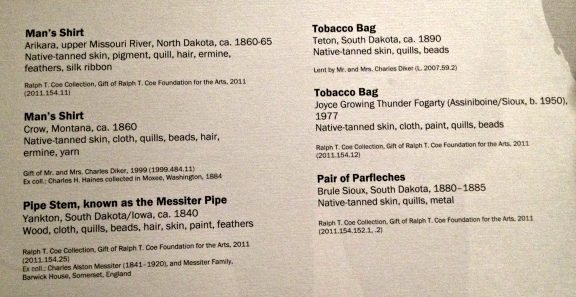

No change: In the case of wonderful items I show at right, five carry tribe labels–Arakara, Crow, Yangton, Teton and Brule Sioux. Only the tobacco bag is attributed to an artist, Joyce Growing Thunder Fogarty–and that is because it’s modern, dating to 1977, and we actually know the name of the maker.

And that, as I wrote, maybe a matter of costs.

Still, I was so pleased with the Plains exhibit and the new labeling that when I ran into a friend that day at the Met, I told her about it. Her immediate response, which she walked back after I explained my enthusiasm for the change, was “political correctness.”

Still, I was so pleased with the Plains exhibit and the new labeling that when I ran into a friend that day at the Met, I told her about it. Her immediate response, which she walked back after I explained my enthusiasm for the change, was “political correctness.”

I don’t agree. I often call out political correctness when I see it (cf. the last two paragraphs here). To me, this is about recognizing something as an object worthy of being in an art museum, as an individual object of artistry by an artist or artisan, and not as a representation of a culture, just as Dan Monroe said above.

Here are links to my previous posts on this subject, here, here and here.

I know some people do not think that Native American utilitarian objects, such as the ghost dance dress or a shirt are art–largely because they are utilitarian. I do not want this post to start that argument again–no one will profit from restating positions that have been stated so many times before, to no avail. Let’s agree to disagree.

Photo Credits: © Judith H. Dobrzynski