I love it when that’s so. I was reminded of this at the new Whitney last week. I had been meaning to return to the subject since I visited the New Britain Museum of American Art several weeks ago to review the Otis Kaye exhibition for The Wall Street Journal.

I love it when that’s so. I was reminded of this at the new Whitney last week. I had been meaning to return to the subject since I visited the New Britain Museum of American Art several weeks ago to review the Otis Kaye exhibition for The Wall Street Journal.

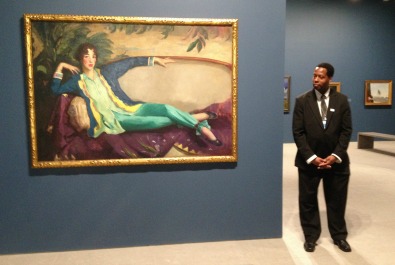

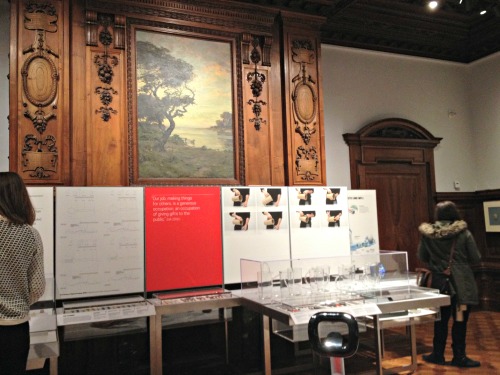

There, the museum seating is not just any seating; it’s a collection of benches bought by the museum from contemporary artists. At the Whitney, as you may have read, the elevators are design by Richard Artschwager (one pictured below, at bottom_.

All of this signals that art is not just an object to hang on a wall, position on a floor or project on a screen. Rather, art  can be part–should be part–of everyday life. I praised the Smith College Museum of Art in 2012 for hiring artists to design its bathrooms and mentioned the NBMAA for its seating. But I didn’t have pictures, and now I do.

can be part–should be part–of everyday life. I praised the Smith College Museum of Art in 2012 for hiring artists to design its bathrooms and mentioned the NBMAA for its seating. But I didn’t have pictures, and now I do.

I’ve pasted them here, along with a couple of the Whitney elevators.

A little apology, though, because in mid-March, I wrote on RCA: “There’s another reason to like the NBMAA (which I’ve both criticized and praised in the past) and I’ll be back with pictures of that reason in the next day or so.”

I apologize–it has been more than a month.

And another apology: although the museum plan lists the artists of the benches, I have misplaced mine and can’t tell who designed these beautiful and varied works.