I was drawn to an exhibition at the Toledo Museum of Art by its title:Â Glorious Splendor: Treasures of Early Christian Art. When I went to see it last month, it was not quite what I expected. Or what the title conjured. But that doesn’t mean it wasn’t a good show. Sometimes an exhibit with a real scholarly thesis is hard to translate into an exhibition that’s easily sold to the public. And naturally even a scholarly curator wants his or her exhibit to be seen!

I was drawn to an exhibition at the Toledo Museum of Art by its title:Â Glorious Splendor: Treasures of Early Christian Art. When I went to see it last month, it was not quite what I expected. Or what the title conjured. But that doesn’t mean it wasn’t a good show. Sometimes an exhibit with a real scholarly thesis is hard to translate into an exhibition that’s easily sold to the public. And naturally even a scholarly curator wants his or her exhibit to be seen!

So, as I wrote in my review of the exhibit for The Wall Street Journal,

A bit oddly, the exhibition undercuts its title (which was probably driven by marketing goals) and a bit of its thesis. About two-thirds of the 28 works here either are secular objects, like jewelry or imperial items, or honor pagan gods, like Jupiter and Aphrodite. Moreover, the earliest Christian object—a glass fragment, with gold leaf, showing Christ giving the law to Ss. Peter and Paul—was made in the late fourth century, decades after Constantine’s death and long after Christianity started to take root in Rome, spawning Christian art. In other words, the exhibition’s span is bigger, the content broader, and the thesis less clearly shown than one might expect.

The thesis was this. quoting myself, that “the art of the first several centuries after the death of Christ shared much with its predecessors—in materials, methods, iconographies and styles—and thus to demonstrate that the Roman empire did not abruptly turn Christian when Constantine became the first Roman emperor to convert in A.D. 337.”

The thesis was this. quoting myself, that “the art of the first several centuries after the death of Christ shared much with its predecessors—in materials, methods, iconographies and styles—and thus to demonstrate that the Roman empire did not abruptly turn Christian when Constantine became the first Roman emperor to convert in A.D. 337.”

And yet:

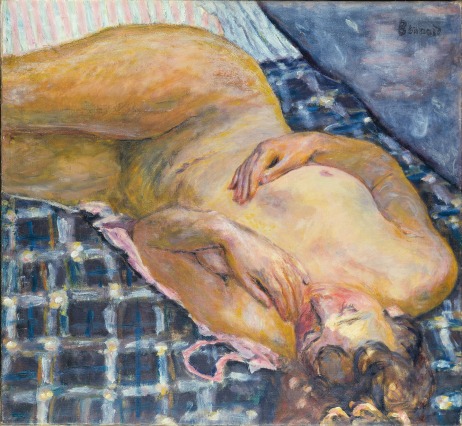

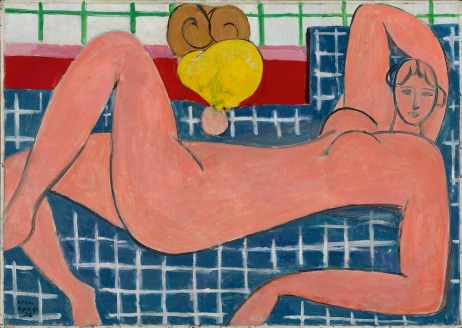

Still, once visitors lean in to enjoy the precious objects on view…they will find much to admire. All but two of the pieces are borrowed from private collections, many have never before been shown in a museum, and who knows when the public will have an opportunity to see them again?

And that’s wonderful, actually. These are gold (the pendant at left is from the 6th or early 7th century, the bracelet from the 6th), or cameos (at right is one from the 6th century), or objects that, I would guess, are rarely asked to be lent. They take some time getting to know. We should have more exhibits that include them.

Glorious Splendor suggests something else about the state of American art museums these days. As they evolve, they may be trending toward a model that presents small, scholarly exhibits that satisfy connoisseurs and large, “popular” exhibits intended to draw crowds.

Glorious Splendor suggests something else about the state of American art museums these days. As they evolve, they may be trending toward a model that presents small, scholarly exhibits that satisfy connoisseurs and large, “popular” exhibits intended to draw crowds.

As long as there is a mix, as long as the scholarly shows receive the funds they need, this may not be bad. Museums have raised expectations about themselves to many groups; now they have to satisfy them.

The Toledo exhibition runs through February 18–enjoy the pictures I’ve posted of a few pieces in it–and my review ran on Nov. 27. Apologies for my delay in getting it online here and on my website.

Photo Credits: Courtesy of the Toledo Museum of Art